When Scott Budnick tells you he’s bringing somebody special, he really means it. Be it Richard Cabral, Common, Governor Newsom, or members of the most famous family on the planet, when he pulls up on your yard, Scott rolls like the President. The film producer and founder of the Anti-Recidivism Coalition moves through prisons like the Mayor of CDCR and greets residents like they’re his adopted family members—because they are. By now, the world has watched episode nine of season five of The Kardashians (Hulu) and caught a glimpse of Kim, Khloe and Scott touring Valley State Prison (VSP) and engaging with residents. Consider these the echoes of what didn’t make it into the show’s final cut.

Kim’s move into social justice advocacy wasn’t easy. “I was super ignorant,” she admitted, “I never knew anybody who had been to prison.” While critics have tried to rationalize the celebritization of her activism, Kim was merely responding to a request from the President. “The White House called me to advise to help change the system of clemency,” Kim said, “and I’m sitting in the Roosevelt Room with, like, a judge… and a lot of really powerful people and I just sat there, like, Oh sh–. I need to know more. I’ve always known my role, but I just wanted to be able to fight for people who have paid their dues to society. I just feel like the system could be so different, and I wanted to fight to fix it. If I knew more, I could do more.” She decided to do more—a lot more.

This sort of candor reveals a humble but self-aware celebrity responding to the social justice prompt of her government, recognizing the moment and using her immense platform to do a special kind of uplifting few humans can do. It’s pretty damn gangster—and noble at the same time. She has brought attention to a domestic human rights issue while wiping the lens through which we take in all of the more veiled but endearing complexities of the human, who came into our space with no make-up, rocked casual baggy gear, walked herself into crowds and extended her hand. Kim didn’t look down at us—she got on eye level with us.

“The first person I ever helped was a woman,” Kim recalled. Alice Marie Johnson, who President Donald Trump pardoned at Kim’s request, met with the President in 2018 just six months into Trump’s new administration. “It was her first low-level drug offense. I was like ‘how does this woman have the same sentence as Charles Manson?’ It just didn’t make sense to me.” After multiple visits to the White House, President Trump signed the FIRST Step Act in 2019 and six months later Kim announced in Vogue magazine she was pursuing a law degree via a legal apprenticeship. CNN’s Van Jones noted her “indispensable role,” and her ability to “unleash the most effective, emotionally intelligent intervention” he’d ever seen—he believes “she’s going to be a singular person in American life.” We’ve never seen more COs fanboy-out and suits posture for camera time than when she hit the yard. It’s a telling metric that reveals the phenomenon of pop culture shaping debates on human nature.

The work doesn’t end when the cameras stop filming. Be it advocating for the removal of dead weight legacies tied to the stranglehold power of a felony record that hyper-achieving, returning citizens like Reginald Dwayne Betts (Freedom Reads), Randall Horton (Radical Reversal), Angel Sanchez, and Michelle Jones each had to jiu jitsu as they climbed into the rafters of academia and engaged in prison reform, or the quiet homelessness of a brother in Tennessee following his release through the FIRST Step act, certain structural problems with policies highlighted by Kim’s altruism only become public because of the rare reach of her megaphone.

Kim once tweeted: “Matthew Charles’s lease application application was rejected again [because] of his criminal record (even [with] me paying his rent in advance). If there are any landlords [with] a 2 bedroom in Nashville willing to give Mr. Charles a 2nd chance, contact…”

Her advocacy prompted both a Daily Mail article and a law professor’s engagement via The Washington Post about how the “law at both the federal and state level makes it very hard for an ex-felon to obtain subsidized housing, which is self-defeating if the goal is to reduce recidivism.” Charitable acts that use an isolated human toll exemplar to highlight a more systemic flaw in the downstream delivery of public policy is precisely how a person with Kim’s reach should use it. It’s not always just about trying to get the high profile cases looked at—there’s a larger conversation being had about the very role of prisons in our society today that too often doesn’t include the stakeholders who are actively subject to the state power being examined. Kim included us.

Erin Haney, a death row attorney and #cut50 policy director describes Kim as “incredible – just the kindest, smartest – I have been so impressed by everything she’s doing and how committed she is.” Jessica Jackson, a lawyer mentoring Kim, praised her ability to grasp analytical legal language owing to her “very calm, very logical way of thinking,” the same calmness that got her through a horrific robbery ordeal and still didn’t push her into the reflexive stiff-arm rebuke of folks who have victimized others the way she was. Victim’s rights groups can’t attack her for minimizing the impact of crime either—Kim had been a crime victim herself long before she decided to become active in the space. She now has the moral high ground. Kim transcended fear and anger.

For a billionairess whose celebrity and cultural finesse is powerful enough to juggle an ongoing beef with Taylor Swift and the leftist flack that comes with standing in the oval with President Donald Trump on sentencing reform, Kim has a remarkable capacity for compassion and just enough of an “IDGAF” ethic not to allow what’s seemingly unpopular or momentary to dictate what she decides to do about the things that have lasting societal impact. She will never get the credit she deserves—hopefully the moments she has with those of us in these blue shirts will feed her in a way media applause can’t. Kim saw those suits hovering while she was here—she gets it.

By traveling to Valley State Prison (VSP), Kim positioned her show’s cameras where they hadn’t been before to reveal the more nuanced and humane angles of an issue largely hidden from public view that tethers, with intentionality, the rehabilitative mission of prisons to the life outcomes for those who reside within them. Who else on her level is doing that?

Albert Berreto, a former youth offender who became a youth mentor and drug counselor, was also present for the Kardashians’ visit to VSP. “I was invited by Scott Budnick,” he said, “so I went and I spoke my story. I talked about the trauma that I went through – being sexually abused, being beaten as a child growing up, all the way till I was 15. And how gangs were my way out. They were what gave me acceptance and meaning. So having Kim listen to all that? I mean, it was just interesting for somebody of her position to want to sit there and listen.”

While bloggers and journalists have speculated about her motivations, we met her, we sat with her, we watched her, she walked into our cells and she platformed our circumstances. She came here—her critics didn’t. Kim is good in every hood, just like Scott is.

Khloe echoed that sentiment, reflecting on how “I don’t think anyone would’ve imagined Kim doing prison reform, going to law school, and doing things people doubted her for.” It would’ve been easier to stand with a more sympathetic slice of humanity who didn’t have dirty hands and virtue signal in the name of any number of safe and worthy charitable causes. Kim is doing the harder thing. Her mother Kris Jenner said that “when you find something that you’re passionate about, it’s not difficult; you don’t have to think about it – it just happens.”

Nolan, a bay area youth offender serving multiple life sentences for murder, got to meet Khloe while Kim got mobbed. “Khloe was low key about it, almost incognito – like, dudes didn’t recognize her – but I did. There were no cameras on us and it was just a hella genuine interaction. For the briefest of moments it was like I wasn’t doomed to die here, ignored or forgotten. I wasn’t able to sit for the in-circle stuff with them like how I got to when I met Sol Guy and the departed Michael Latt with Scott a while back, but I appreciated that organic encounter with Khloe way more than being on camera. Sometimes just being able to interact with a real person is the best medicine. I see why so many people consider Khloe their favorite Kardashian – she has a ride or die kind-of authenticity that makes you feel like she’s in your corner.” These are the reflections that get spoken into our poetry circles and become poems in our Barz Behind Bars creative arts workshop.

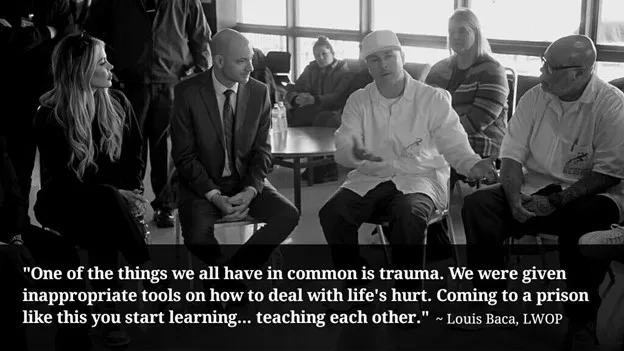

Louis Baca, a Bay Area youth offender serving a life without parole (LWOP) sentence for a drive-by shooting he committed as a teen, has served over a quarter century already. “I got to meet Khloe, shake her hand and speak with her about trauma. She was normal as hell and treated me like a real person. I also got to meet Associate Director Lemon and speak about possibility. I first met Scott over a decade ago with Richard Cabral in High Desert back before there was any legislation for youth offenders at all. I’m one of those youth offender LWOPs left behind by a gap in the law that isn’t applying the developmental brain science mitigation to our cohort of people age eighteen to twenty-five – we’re not being afforded that diminished culpability basis to earn a second chance to demonstrate our parole suitability the way similarly-aged youth offender lifers are. We’ve been left behind.”

Louis advocates for a legal remedy. “I’ll die here unless that happens, as will the other men who were featured in the show’s episode. I resisted the temptation to lobby the camera and instead, I just shared the real about how we all got here and how we help each other – but I’d be lying if I didn’t say that my hope revolves around my situation, because it’s an indefensible stasis we can’t remain in as a society. I’m hoping that this area of activism is that next step in what changes to maybe give us a second chance too. I want that chance to present my transformation, but if my destiny is to die here, then at least put me and other cats like me in a studio and let us curate from our wreckage the teachable moment life lessons that might be exported to save the next man. I did a drive-by shooting, something kids are doing daily. Make me that tool. Use my life, put it in podcasts, publish it in a rhyme book – turn it into a lesson plan. Don’t just come gawk at us like zoo animals. Either let me earn my freedom or fully harness my life to save somebody else’s – but don’t half-step and don’t leave me idle. Let us be that reckoning.”

He wants to create media that saves his peers. “They trained and taught and educated me, right? So, use me. We got a squad of well-meaning and capable guys here ready to be of service. Imagine if we put the Trauma Talks curriculum into a prison podcast and put it on Edovo? Fritzi Horstman already agreed to let our Barz Behind Bars group do it right here at VSP – so why isn’t Mr. Lemon, DRP or anybody talking to us about that? Freedom Reads, RadicalReversal – they’re all standing there inviting us to do just that in their name. If you really wanna change the culture then start allowing those of us who are creative and communicative to shape it using the programmatic tools CDCR already paid grant money for us to use. Let us be that inside-out change agent. It’s time we become the makers of the life-saving content we didn’t have coming up. Put us all in the Media Center, turn the mic on and let us show you what we can do. I tip my cap to Scott for including us and I send my respect to Kim and her sisters for using their influence to center our humanity. I hope they come back and hold symposiums on some next steps. God bless y’all.”

Kenneth Coley, a repeat offender and third-striker from Los Angeles serving life for robbery, used to resent the attention youth offenders received—it used to make him envious of the opportunities he’d already thrown away. “I get it now. I see how Scott has leveraged his life to save others – and now he’s inspiring people like Kim and her family – people who are even more famous than he is – to reframe what prisons could be. I blew my chances, but the place I get to do my time at is a way better place than the system that molded me with crazy violence, Greenwall cops, racial segregation and fewer opportunities. That’s because of what Scott has poured into this place. I see that now. It’s a good thing. These youngsters need to be saved.”

After the episode aired, Kim, Kendall and the Lord himself (a different Scott), swerved out to the youth offender fire camp where many of our VSP bros who transferred there are now doing the dangerous job of fighting fires to try and save the homes of taxpayers. The K-sisters flicked it up with some of our homies for TMZ.com in a stunning show of normalcy which is exceedingly rare for celebrities that fly at their altitude. These are not culture-vulture cosplay moves either—it’s a uniquely compassionate form of activism even politicians covet. Selflessly using the digital influence that typically drives their commercial interests to normalize conversations about how we might better use state power to nurture life instead of starving it is the sort of civic engagement abolitionists like Doran Larson say are necessary in order to diminish the stigma tied to prisons and those held captive by them.

We see more than a photo on TMZ—we see media shaping hearts and minds. Once the stigma is erased, people can focus on the humanitarian piece. You see, for the laws to change the optics have to change—and so, we have to trade in these tired and marginalizing colonial terms like inmate, prisoner, felon, and convict for identifiers that proclaim the future we are all chasing: student, mentor, and returning citizen. We have to reclaim the language, stand next to one another, cease the othering, take those photos, amplify success and normalize engagements that showcase the slices of life missing from view.

They built this system using word weapons like super-predator, dangerous few, and lost cause. Our current President wrote and helped institutionalize the very architecture of policing, prosecution and prison construction that our current Vice President used to prosecute BIPOC citizens for smoking weed while Attorney General. The cool kids are finally saying something about it—perhaps popularity can bully the body politic after all.

“What are we supposed to do,” Khloe asked, “just throw people away? People deserve second chances.” We all have to choose a side: are you for mercy and redemption—or petty vengeance?

Ben Frandsen is a former youth offender mentor and lifer who paroled from VSP, graduated from UCLA and founded the nonprofit Ben Free Project. “These,” he said, “are precisely the sort of outside-in engagements incarcerated citizens need more of, because the ripple effects of the media aggregated from these moments is the spark that motivates a college student to volunteer as an intern and prompts a state’s Senator or Governor to reconsider their position on justice issues.”

Khloe said “I dont think we highlight a lot of the creativity and the transformations.” Frandsen doubled down on that by advocating for the need to “build content verticals developed in partnership with stakeholders that harness media tools like anthologies, podcasts and journalism projects like this that let folks be the authors of their lived experience. Digital humanities archives can help shape the college students who will become the teachers, parole officers and public administration officials who steer prisons into the next century. We need to build these platforms of agency. The more we let residents speak, write, draw, paint, create music and produce their own content, the better informed the public will become. That is the freedom we imagine.”

Frandsen, now attending graduate school in the MFA program at CSU San Diego, says returning citizens are the surrogates who need to be out in front convincing policy makers to extend second chances using their lives as the proof of concept. “Beyond leading with the empathy argument that is tied to questioning why we throw away our youngest offenders, those of us who have emerged from confinement have an obligation to be that collective human land bridge that connects back to those left behind, because our success is that most compelling evidence of the need for reforms that serve our youngest carceral population. This is an area of activism that Scott has pioneered and elevated to an art form – it moves the culture as much as it does the law, funders and thought leaders. Compassion is really about helping people who you know can’t do anything to help you back. Kim, her family and Scott are doing a lot of important work off-camera too that you can’t see – and we have a Governor who has really embraced the systemic pivots that make this a hopeful moment for the California model. It’s an all hands on deck moment.”

Mass incarceration is the very structural legacy of slavery, Jim Crow and the commodification of the surplus labor of the American ghetto. The cotton gin and plantation society built the same Wall Street economy that created the hedge funds that drive business ventures today. Our prisons still compel indentured servitude via the compulsory authority of the state Constitution—recognize these stains for what they are. Carceral studies by historians like Elizabeth Hinton (From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime), Heather Anne Thompson (Blood in the Water), Ibram X. Kendi (Stamped from the Beginning), and Ray R. Album (The Golden State’s Veiled Dichotomy) have given us road maps to travel and brain food to devour. Everyone doing this action work should be reading these books and articulating the activist philosophy.

The Gwendolyn Brooks poem “To Prisoners” describes a human garden—we are those flowers under a scarecrow who too often blocks out the sun. We’re yearning for a gardener. Before there can be freedom, we have to imagine it. In order to move the culture we have to seed the objective. Public opinion is shaped by what the public can see. The visuals matter—the narratives matter. Unlike political campaign seasons that come and go, these messages can’t flip and the messengers can’t be transient—consistency is the watch word. Nobody has been more consistently engaged in this work than Scott and nobody has enlisted more allies in the fight. Kim just might be his nuclear weapon.

After having traveled into several of the Golden State’s prisons and personally taken the measure of the problem, it looks like Kim is perhaps about to flex her muscles by recruiting more celebs to campaign in earnest for the youth offender reforms the system is begging for. “I always have such a life-changing experience every time I go and visit a prison and meet new people. I think my family and friends would really benefit from experiencing this,” Kim said. “Everyone comes into the system and you want them to come out better people right? I think we need as many voices as we can.”

Stay tuned for our long-form Inner Views profile of the Kardashians’ visit to VSP and our roundtable discussion with the youth offenders there serving LWOP who advocate for second chance legislation at @BFPInnerViews.

Photos courtesy of The Mundo Press