by Mark Daigre

In The Waste Land T.S. Eliot put forth that April is the cruelest month. I disagree. For myself at least, the cruelest month has got to be October. Let me explain.

On October 5, I went in front of the Parole Board, receiving a denial for a period of five years. That was bad enough, but I’m not even close to being done. Michael, my cellmate and friend of the last ten years went before the Board three weeks later, on the 26th, getting a three-year denial, and that night after he went to sleep, had a massive heart attack.

I woke up at 6:00 AM on the morning of the 27th, did my morning routine, then noticed that Michael hadn’t moved, I tapped on the bunk, expecting a response. Nothing happened. So I tapped again, this time a little louder—same result. At this point I said, “Oh Crap” in my mind and tapped on Michael’s foot. He was cold, stiff and unresponsive.

In that moment, my heart shattered. I’ve known Michael for over a decade, we have been cellies for at least eight of the last ten years and bunk-mates for 90% of that time.

He was one of the few people in my life that I could tell anything and be secure in the absolute knowledge that not only would he not repeat what I said without my permission, he would also do his best to find some way to identify with that experience, not only accepting me and my experience—but also find a way to love me at the same time.

Michael taught me so much over the years that we lived together. I watched as he genuinely forgave another person who truly did him wrong—telling an untruth that put Michael in Ad-Seg for a few months while that bogus report was investigated. Michael not only forgave that person but then went out of his way to continue communicating with them; I’m not so sure that I would have been able to anything like that as quickly and easily as he did. He showed me over and over again that forgiveness could be granted to people who “didn’t deserve it.”

He also taught me a tremendous amount about patience. Michael could take a week or more to make a paper-towel dispenser from the thin sheets of cardboard that our lunches came in, held together with soap. He could also take three or four days to make and put up a hook to hang a hat on—again using that same lunchbox cardboard and soap, sometimes with a bent paperclip added in for the hat.

Michael and I could spend hours together without saying a word, or we could talk for three or four hours straight. We had worked through the “uncomfortable silence” part of our relationship and moved into a place of comfort and, not ”just” friendship, but a place of true ally-ship. We both absolutely knew that the other was on our side, no matter what. I knew that I could trust Michael and I’m pretty sure he knew he could trust me.

On the night of the 26th one of the last things that I said to Michael was that I was, in a very selfish way, happy that I would not need to find a new Bunkie for a couple of years.

Boy did he prove me wrong!

On that morning, once I realized that Michael was no longer breathing, I leaned over and gave him a kiss on his forehead, something I’d never done before. Michael and l were never physical in our relationship; I can think of only a couple of times that we hugged, and I had never even thought about kissing him before. I did, however, have some idea of what was about to happen, this is prison after all. So I am very glad that I took that opportunity to make sure that the first touch he received was that of a loving friend.

I told the other people in our living space that Michael wasn’t going to wake up and that they should be ready to leave the space for a while, as the Investigative Services Unit (I.S.U. or “Squad”) would be in our space for a while. Then I went downstairs and told one of his friends that Michael wasn’t waking up and invited him to go in and say “Goodbye.” He felt that he had to decline, not out of cold-heartedness, but because everything we do is recorded on camera and he didn’t want to be seen going into our space after Michael had passed.

I then went to the officer’s station and told them about Michael. I also told them that he had a D. N. R. or “Do Not Resuscitate” order on file and that no measures should be taken to bring him back. That request was ignored and one of the officers told me that they had to do their jobs and they began performing chest compressions until medical staff arrived then they took over and began to administer shocks from a defibrillator as well.

Our housing unit has individual showers that can be locked from the outside. I, and the rest of the people who live in our space, were each locked into a shower alone until the immediate investigation was complete. I kept calling out to officers and medical staff as they walked by, telling them that Michael had a DNR on file and that they should stop working on him. I was ignored.

In California prisons, when a person’s file is called up on the computer, at the very top of their page, if they have a DNR, it shows. As far as I can tell, nobody looked at his file, at least until they had been working on him for more than 20 minutes. As it should be, this was an “Emergency” situation after all.

Michael was born with a heart defect, he was on his third Mitral Valve, and it had been in place for some 30 years. He had been going out to see heart specialists for his entire life inclusive of his prison career, and it was well known by medical staff how fragile his heart was.

In some ways, I am very angry with Michael. When we first moved in together, he informed me of his DNR and specifically asked me to not provide or ask for assistance if he was ever in serious medical distress. I agreed. At the time it wasn’t a big ask, we barely knew each other and I knew that I could respect his request. After all, it was his life that he was talking about.

So even if I had heard him struggling in the night, I morally could not do anything to help him. I couldn’t give CPR, I couldn’t call out for help. I couldn’t save his life.

Please make no mistake here; I am very, very glad that I was allowed to discover Michael that morning. I am also so very glad that I was able to call his sister and tell her that I had been the first person to lay hands on his body that morning and that those hands were of a friend who loves him. I am also glad that I was able to give the people that were living in the space with us a “heads-up” about being locked out of our space for a few hours that morning. And I am also very appreciative of both custody and medical staff for doing what anybody is supposed to do when someone discovered is not breathing, i.e. giving CPR and making every reasonable effort to save their life.

During the autopsy, it was concluded that Michael had passed over sometime between midnight and 2:00 am. By the time I discovered him, he was not only unresponsive but cold as well, and full rigor mortis had set in. This made the efforts by both correctional and medical staff all the more upsetting. They were trying to push blood that had become solid through his system and inflate lungs that couldn’t move.

Michael had previously told me that he had been “pulled back” a couple of times before in his life and he didn’t want to have that ever happen again.

I know from my life prior to prison, that giving CPR can be physically, mentally and emotionally exhausting. Giving a cold, stiff corpse CPR is all the more difficult and often induces some level of trauma on those performing these life-saving measures, as well as bystanders.

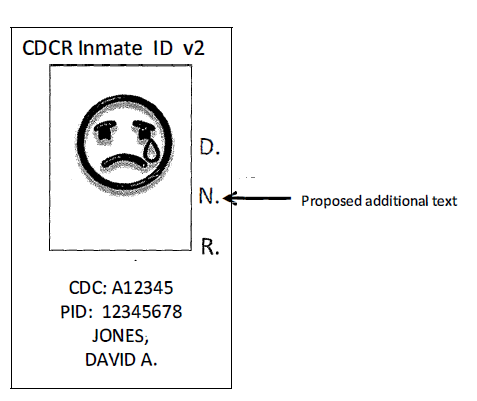

I have told you all of this because I have a request; can we add to the front of the State Prison ID Card that all incarcerated persons have/must carry, an indication that a DNR is on file? My suggestion is that it be printed,-in refalongside the person;s photo, reading from top to bottom in letters big enough to be easily noticed during a medical emergency or crises “D.N.R.”. (Please see example on the following page.)

Doing this would allow those incarcerated persons who have a DNR on file have their wishes and final directives respected and followed. It would also give custody and medical staff direction in a quick and easy to recognize manner while a highly charged situation is occurring.

This addition to the State ID Card would require little to no cost to the state to implement, and could require some level of Training for both Custody and Medical Staff. This training could be given during regular I.S.T. “or In Service Training” for custody staff and yearly “Block Training” for medical staff.