It is difficult to know what happened back in 2014 when at San Jose State University two police officers, including now-Yolo County Deputy DA Frits van der Hoek, were involved in a fatal shooting. The police claim that they had no choice and that they were firing on the man as he advanced on them. We have not been allowed to see the video and the stills show that the man may have been retreating.

Two people who did see the video claim to have seen no aggressive move by the man. The DA’s office in Santa Clara County cleared the officers of criminal wrongdoing but that’s hardly reassuring. We saw a pretty questionable encounter in Staten Island result in no criminal charges either.

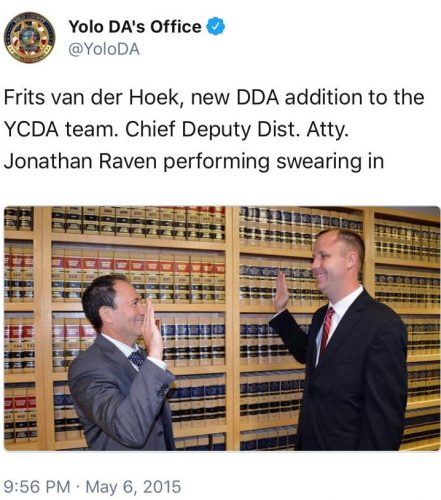

What we do know is that, given the concerns about the relationship between DAs and police, it is absolutely inappropriate for the Yolo County DA’s Office to hire Mr. van der Hoek, given the circumstances of that shooting.

Under Yolo County DA Jeff Reisig, there has been only one instance in which an on-duty police officer faced charges for his conduct and, in that case, he was not acting under the color of any sort of authority. That was West Sacramento Police Officer Sergio Alvarez, who was eventually convicted of multiple counts of rape that were committed against women while on duty. In that case, there was no gray line between official conduct and illegal misconduct.

However, in every case where excessive force occurred, the DA’s office has failed to prosecute. That includes the 2009 fatal shooting of Luis Gutierrez by sheriff’s deputies in Woodland. That

includes the 2011 Pepper Spray incident where the DA’s office found no probable cause that a crime was committed, even though multiple reports faulted Lt. John Pike, claiming he used unauthorized and excessive force against unarmed and seated protesters.

The DA’s office elected to charge Brienna Holmes with resisting arrest rather than charge the officer with throwing the protester onto the hood of a police car. And the DA’s office chose to charge the Picnic Day 5 and not the officers in the recent incident in Davis.

There was the 2012 Tasering of Tatiana Bush and Jerome Wren by Officer Nicholas Benson that remains troubling. The DA, of course, neglected to charge the officer with a crime, but did charge Ms. Bush and Mr. Wren with resisting arrest before finally dropping the charges.

The Davis PD would fire Officer Benson, but he managed to get a job with the Galt Police Department, despite an apparent strong warning from Davis PD that Mr. Benson had engaged in multiple use-of-force complaints. The failure of the DA’s office to step in allowed Mr. Benson to get a job elsewhere, where he of course used excessive force again and a lawsuit remains pending in that case.

In 2005, several West Sacramento police savagely beat brothers Ernesto and Fermin Galvan, claiming the brothers were resisting arrest and that necessary force was used. The DA charged the brothers with resisting and obstructing officers, with no underlying charge, and the case wound through three mistrials, with the DA finally dropping the case. The DA never filed charges against any of the officers, despite evidence that excessive force had been used, and it took the brothers filing a federal civil case to finally achieve some compensation for their severe injuries.

On Tuesday, numerous activists complained about the lack of discipline against the officers involved in the Picnic Day incident.

But the message sent by the DA’s office in hiring Mr. van der Hoek when they knew he had faced criticism and an investigation into his actions is hard to swallow.

One of the biggest complaints since the nation began focusing on officer-involved shootings has been the lack of ability of the legal system to deal with these cases appropriately. A large number of them – in fact the vast majority of such cases – have resulted in zero prosecutions. Where prosecutions have occurred, even in cases that are fairly clear, there are rarely if ever successful convictions.

Caren Morrison, writing in December of 2015 in the wake of the charges against officers who shot Laquan McDonald in Chicago, is a former federal prosecutor. She has studied how prosecutors handle police violence cases. She asked: “How do they deal with the conflict of interest raised by investigating the police departments they work with? Who determines whether a civilian death is justified, as the vast majority are found to be?”

She said, “The results are not pretty.”

For her, “The real issue is that the prosecutor controls whether a case goes forward at all. This is true whether the case proceeds by indictment or preliminary hearing. Other than public opinion and the possible pressures of reelection, no one oversees the prosecutors.”

Critics have pointed to the close and necessary relationship between the police and prosecutors. Prosecutors have to rely on police to properly arrest, collect evidence and of course testify in court in order to win prosecutions and, by going after police officers, the theory goes that prosecutors risk that relationship.

In a sweeping story at the end of 2015, The Guardian published an exposé which found that in the year 2015, DAs cleared police of wrongdoing in 217 cases of police killings. “The total represented 85% of all killings by police that were ruled justified in 2015,” according to a Guardian analysis. That included the case of 12-year-old Tamir Rice killed in Cleveland in 2014.

Writes the Guardian: “Criminologists, civil liberties activists and lawmakers said the arrangements created serious conflicts of interest at the heart of the criminal justice system’s response to killings by police.”

“Prosecutors work with police day in, day out, and typically they’re reluctant to criticise them or investigate them,” said Prof Samuel Walker of the University of Nebraska. Describing as a cause for concern the case of Omaha Officer Alvin Lugod, where the prosecutor declined to indict him for shooting an unarmed man in the back, Walker said: “A major change in our standard legal practice, and the structure of our criminal justice system, is required.”

So now the DA’s office has hired a police officer involved in one of those controversial shootings to be one of its Deputy DAs.

“I know how the system works, how it’s supposed to work,” said Laurie Valdez, the domestic partner of the victim in the San Jose incident. “I am so devastated. They’re still getting away with it.”

“I did not see Antonio make any aggressive move in the video,” Asian Law Alliance executive director Richard Konda said after viewing the video. “I think charges should be filed in this case.”

The message that the DA now sends, not only by its charging and lack of charging decisions and now by its hiring decision, is that it is not going to take the issue of police violence seriously. All of the protesters who came out on Sunday in Woodland and Tuesday in Davis are justified in their skepticism and, going forward, this will remain a critical case in point.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

“The failure of the DA’s office to step in, allowed Mr. Benson to get a job elsewhere where he of course used excessive force again and a lawsuit remains pending in that case.”

A district attorney has no legal authority or justification to “step in” and spontaneously alter what was a lawful pursuit of employment by an individual.

DA Reisig must comply with employment and labor law just like everyone else. He cannot, on his own initiative, contact a prospective employer and cast aspersions on somebody without specific legal procedures first being obeyed.

If (Big if) the prospective employer had a written and signed waiver from the applicant–and if the prospective employer had contacted Reisig and supplied a copy of the waiver–then the Yolo DA could have spoken on the record.

The DA’s office failed nobody. They complied with longstanding employment law.

The District Attorney could have and should have ruled that the police officer in that case unlawfully assaulted the individual he tasered – which is why he was fired by DPD.

More than a bit weird…

If you want to criticize the DA for not bringing charges, if DPD/City requested him to, fine.

The DA cannot “rule”… takes someone in a black robe to do that.

But the DA was not a part of the decision by the City. DPD cannot fire… only the City can (probably requiring CM approval, not sure)[the DA definitely cannot fire a DPD officer… that is absurd!]… was the officer “fired”, or given the opportunity to resign to avoid being fired? Given the facts, only the City could have shared info with Galt.

To the DA, the circumstances of the firing would be “hearsay”.

Your points at best, are “off target”…

Should have said “charged him with”

Phil

Then what mechanism is there to prevent police who abuse their powers, and are known to their superiors or someone in the DAs office to simply obtain a job elsewhere ? I find it hard to believe given the safety mechanisms that pertain to surgeons ( although no system is perfect) to believe there is no protective mechanism at all for our communities.

At least in California, law enforcement agencies doing the hiring bear the legal and administrative burden of vetting prospective employees. Failure to do this has high liability consequences.

Former employers cannot just volunteer work history, they respond to inquiries, and only with the presentation of a signed waiver of disclosure.

To say that a district attorney is obliged to speak on any disparaging history, may be arguable on moral grounds. But DA’s comply with and enforce legal standards. Besides, district attorneys cannot adequately summarize a police officer’s performance because they see very little of the overall job performance of any law enforcement officer. Using a medical analogy, it would be like asking a pharmacist to judge your qualities as a medical doctor.

“Using a medical analogy, it would be like asking a pharmacist to judge your qualities as a medical doctor.”

Interesting that you should have picked that particular analogy. A short anecdote to illustrate how these issues are handled in medicine. When I was a new attending physician within my first month in a new facility, I had a woman come in with a condition for which Tylenol # 3 with a prescription limit of #30 was a standard treatment. On the way to the pharmacy, she altered the prescription ( still on paper at the time) to read #300. I got a call from the pharmacist for clarification and when I assured him that it was #30, he told me they had assumed as much and already called the police while stalling her. He then made the comment that if it had been for #300 he would have been contacting my chief of department instead. We briefly laughed, but I had no doubt that he would have done so.

In medicine, if we see someone doing something that we know to be egregiously wrong, we have an obligation to report it either up their chain of command or ours depending on circumstances. Given the potential for patient harm, the consequences are just too serious to look the other way although some manage to do so. Frankly, I am unpleasantly surprised to learn that the same does not apply to the police given their ability to harm others through inappropriate use of power.