Part One: California’s Private Judges, a Rolling Investigation

By Susan Bassi

Most people in California are unaware that, over 25 years ago, California began privatizing the public court system by authorizing the use of paid “private judges” in certain divorce, family law, and other cases. When the privatization plan was being debated, a state court judge, James Ford, pointed out that the plan to pay private judges to do the work of public court judges was probably criminal.

PANDEMIC PRIVATE JUDGES

Parties to a lawsuit in California state courts can hire a “private” judge to decide parts or all of their case in lieu of a public court judge. Some divorce attorneys deceptively tell clients that, by paying a lawyer to act as a private judge, a divorce case will be cheaper, faster, and more private than the public court system.

During the pandemic, public court functions were severely restricted and cases backed up. As a result, many family law attorneys encouraged their middle-class and high asset clients to hire  private judges.

private judges.

In a LA, middle-class divorce attorney Melinda Johnson billed over $200,000, for her private judge’s fees. Court records show that a year after the splitting spouses agreed to hire Johnson, they had been charged not only $200,000 for Johnson, but also fees to JAMS (the private judge rental company, Judicial Arbitration and Mediation Services, Inc.), and court reporter fees, on top of fees paid to their own attorneys. Costs they were not told about when they agreed to use a private judge.

Attorney Dennis Wasser of the Wasser, Cooperman & Mandles law firm, represented the husband in the case. The husband paid private judge Johnson fees at a rate of $750 per hour. Johnson billed for hearings, legal research, notes review, completing domestic violence court forms, and drafted orders. Judge tasks the couple would not have had to pay for in public court. Laura Wasser, Dennis Wasser’s daughter and partner, represented Britney Spears in her divorce and Angelina Jolie, whom Wasser put into private judging back in 2017.

In the LA case, Judge Johnson failed to register the wife’s restraining order in the state law enforcement CLETS system (California Law Enforcement Telecommunications System).

In 2022, after it became apparent that the cost of the private judge arrangement was unjustified and unsustainable, the wife went back to public court to terminate Johnson’s private judge appointment. Removing Johnson should have been easy because the private judge agreement Johnson was working under had an upcoming expiration date. By law, the private judge would be off the case when the agreement expired. Instead, the wife had to fight a request made by the husband to extend the private judge appointment.

NOT A PRIVATE AFFAIR

California divorce cases are not private. Divorce hearings and files are deemed matters of public interest. The public has a right to oversee the equitable division of community property, proper support of children and how much splitting spouses are paying their lawyers.

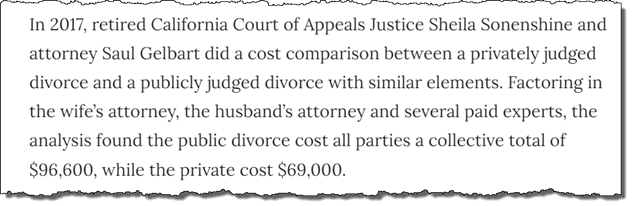

Retired Justice Shelia Sonenshine worked as a JAMS private judge for years. In 2019, she told a reporter that she and attorney Saul Gelbart had conducted a study and found that, after factoring in the wife’s attorney, the husband’s attorney and paid experts, public divorce cost splitting spouses $96,600. By comparison, Sonenshine claimed private judge divorce cost a mere $69,000.

PRIVATE JUDGES NEED NOT BE AN ATTORNEY

“Private” judge is a misnomer, as is the notion that a “private” judge must be an attorney. “Private” judging does not have to be conducted by an attorney charging $750 per hour, but attorneys and “private” judges who are attorneys do not mention the non-lawyer alternative.

It is unknown how many lawyers act as private judges. Neither California’s courts nor the State Bar keeps lists to inform legal consumers about the costs and quality of legal work private judges perform for fees charged from $350 to $950 per hour.

SECRET DOCKETS

California’s courts are required to post lists of all cases that have moved before a private judge. However, the courts have largely failed to furnish the lists. Santa Clara County began to post a private judge list beginning in 2017. However, in posting only 28 cases, including Google Founder Sergey Brin’s first divorce, hundreds of other divorce cases that should be on the list seemingly disappeared from public view and oversight.

Without the lists, litigants and their lawyers cannot investigate if a suggested private judge receives a flow of business from an opposing attorney that could assure favorable rulings for the client whose attorney pays the private judge the most money. Without lists of private judge dockets, it is impossible for parties and their lawyers to determine if the private judge they select and pay to handle divorce, custody or domestic violence matters has the necessary training and experience.

Without the lists, litigants and their lawyers cannot investigate if a suggested private judge receives a flow of business from an opposing attorney that could assure favorable rulings for the client whose attorney pays the private judge the most money. Without lists of private judge dockets, it is impossible for parties and their lawyers to determine if the private judge they select and pay to handle divorce, custody or domestic violence matters has the necessary training and experience.

HIDING RECORDS BEHIND THE BAR

In October of 2021, private judge Michael Smith called the police on reporters lawfully seeking access to inspect public court files, hearing notices and domestic violence CLETS restraining orders, contained in Smith’s private offices based on his appointment as a private judge.

Smith who has acted as a private judge since at least 2013, was reported to the state bar for blocking access to public records in violation of Government Code section 6200.

There are no public records of discipline taken against an attorney who failed to follow the law when acting as a private judge.

PRIVATE JUDGE BUSINESS – FOLLOWING THE MONEY

On average, California’s public court judges are paid $200,000 per year. They work in courtrooms and courthouses open to the public. Public court judges are required to publicly disclose their financial conflicts of interest on 700 Forms. Each year public court judges are responsible for hearing hundreds of divorce, custody, probate, and domestic violence cases at taxpayer expense.

By comparison, private judges are not obligated to publicly disclose their financial conflicts of interest. They are however obligated to disclose the business the lawyers in the case regularly bring to the private judge business where the private judge is associated. As a matter of law they must also disclose information that might cause a reasonable person to question if the private judge could be fair.

PAYING FOR SECRET VIOLENCE

Domestic violence is a matter of public interest. Abuse secreted in the privacy of the family home is harmful and compromises a spouse’s fundamental right to live in peace inside their own home. Left unrecognized by a family court judge, domestic violence poses a threat to vulnerable spouses, children, employers, neighbors and police.

DEATH OF THE NON- CLETS RESTRAINING ORDERS

Melinda Johnson was appointed as a private judge in the Reichental divorce, and she purportedly issued a DVRO against the wife. In a December of 2021 published decision, the Court of Appeal noted Johnson had abused her discretion by filing a non-CLETS DVRO. The case was returned to Johnson, who was privately paid more fees to correct the order.

The attorney representing the wife in the Reichental matter, Jude Egan, wrote an article about the case, which appeared in The Recorder, a legal publication. Egan’s op- ed was titled Death of the non- CLETS Domestic Violence Restraining Order.

Egan noted that a non-CLETS order had been previously used in family court as a middle ground. A warning of sorts to stop abuse without going so far as to issue a CLETS order.

Public policy seeks to assure family courts make restraining order applications a statutory priority over all other family court matters. However, there is no such thing as a “non-CLETS” DVRO in California as of 2020.

Public court judges aim to hear cases involving domestic violence within 21 days of allegations of abuse in connection with a divorce or intimate partner relationship.

Melinda Johnson’s case dockets and JAMS’ billing statements reveal that,as she acted as a private judge and ruled in domestic violence matters, Johnson regularly failed to publicly notice hearings, denied public access to private judge court files, and exceeded the time to decide the matter as mandated by public policy.

PRIVATE JUDGE THREAT TO POLICE OFFICER SAFETY

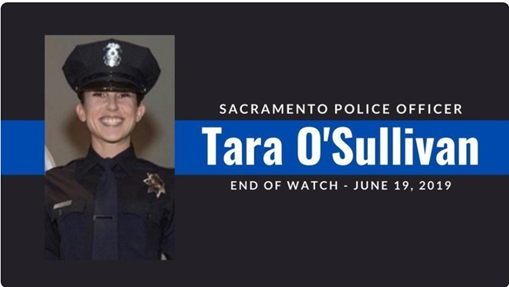

On June 19, 2019, Sacramento police officer Tara ‘O Sullivan was killed after responding to a domestic violence call. During the pandemic, a Change.org petition was created to support the building of a Memorial Bridge in Officer Sullivan’s memory. The project is supported by domestic violence survivors, advocates and police officers.

In 2020 the state legislature added Family Code section 6380, requiring judges issuing domestic violence orders to assure those orders are communicated to law enforcement via CLETS, a California Law Enforcement Telecommunications Systems. Proper CLETS notification may have saved Officer Sullivan’s life, as she would have been forewarned of the history of domestic violence and of a possible threat lurking in the secrecy of the home.

CLETS restraining orders are intended to protect a spouse from repeated abuse and unwanted contact. A restrained party typically loses their Second Amendment Rights and is required to turn in their guns.

DVRO CLETS orders can impact employment, a parent’s ability to pay child support and custody of one’s own children. Firefighters, police officers, state employees and lawyers can find employment terminated should they become named as a restrained party in a CLETS Domestic Violence Restraining Order, DVRO.

Now, when a family court judge finds an application rises to a level of concern, a temporary order is issued until such time as a formal hearing can be held. Once a family court judge issues an order to restrain one of the parties, public court staff communicate the order to the law enforcement CLETS database managed by the state’s Attorney General.

POLICE OFFICER TRAINING IN DOMESTIC VIOLENCE CASES

California’s Peace Officer Standards and Trainings, POST, requires police officers to confirm the existence of a CLETS DVRO when responding to a domestic violence call. If that CLETS order has not been properly communicated to police officers such that they are aware of a history of violence or possible threats to their safety, they are vulnerable to the very harm seen in circumstances surrounding Officer Sullivan’s tragic death.

Private judges have no authority to communicate a CLETS DVRO to law enforcement as public courts do. Risk of a DVRO not being entered into CLETS endangers both the victim spouse, law enforcement officers called to help and the society at large.

Susan Bassi is an investigative journalist who has been investigating the use of private judges in California’s middle class and high asset divorce, custody and probate matters for nearly a decade. As part of a Diversion Program offered by Santa Clara County Superior Court, Susan has agreed to provide 45 hours of pro bono work to the Davis Vanguard as an effort to bring greater public awareness about private judging, domestic violence, policing and the importance of local news. To support this series, please donate to Davis Vanguard a 501 3 c Charity #46-3013126