Editor’s note: the following are excerpts from the Executive Summary of the California reparations report… Read the full report here.

V Housing Segregation

Nationally

America’s racial hierarchy was the foundation of a system of segregation in the United States after the Civil War. The aim of segregation was not only to separate, but also to force African Americans to live in worse conditions in nearly every aspect of life.

Government actors, working with private individuals, actively segregated America into African American and white neighborhoods. Although this system of segregation was called Jim Crow in the South, it existed by less obvious, yet effective, means throughout the entire country, including in California.

During enslavement, about 90 percent of African Americans were forced to live in the South. Immediately after the Civil War, the country was racially and geographically configured in ways that were different from the way it is segregated today. Throughout the 20th century, American federal, state, and local municipal governments expanded and solidified segregation efforts through zoning ordinances, slum clearance policies, construction of parks and freeways through the middle of African American neighborhoods, and public housing siting decisions. Courts enforced racially restrictive covenants and prevented homes from being sold to African Americans until the late 1940s.

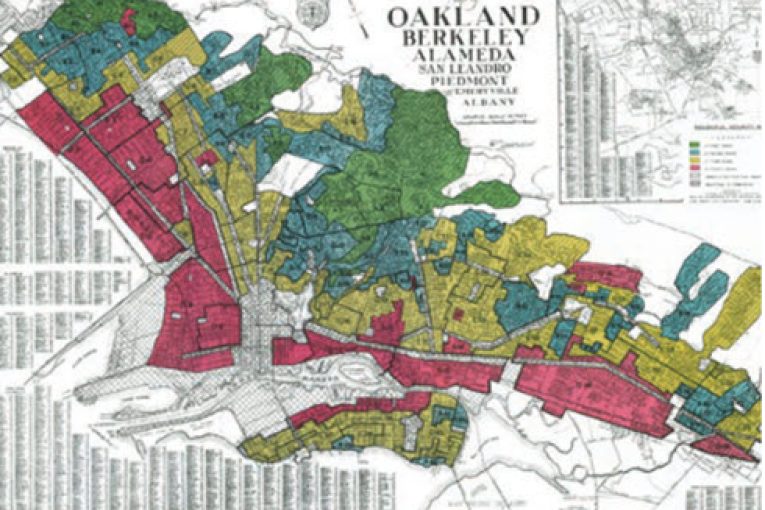

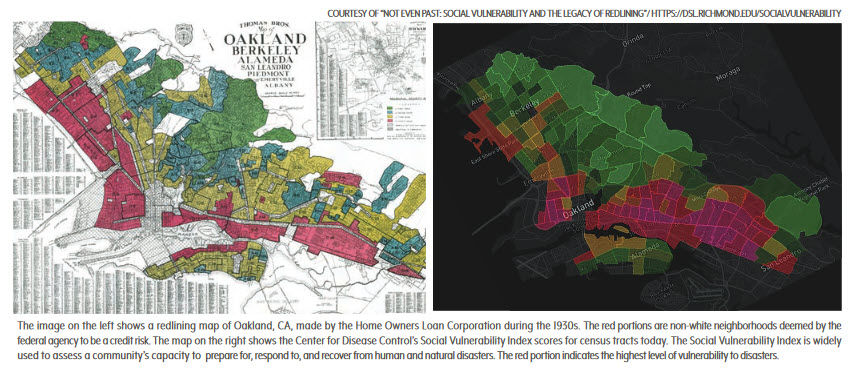

The federal government used redlining to deny African Americans equal access to the capital needed to buy a single-family home at the same time that it subsidized white Americans’ efforts to own the same type of home. As President Herbert Hoover stated in 1931, single-family homes were “expressions of racial longing” and “[t]hat our people should live in their own homes is a sentiment deep in the heart of our race.”

The passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968 outlawed housing discrimination, but did not fix the structures put in place by 100 years of discriminatory government policies; residential segregation continues today.

The average urban African American person in 1890 lived in a neighborhood that was only 27 percent African American. In 2019, America is as segregated as it was in the 1940s, with the average urban African American living in a neighborhood that is 44 percent African American. Better jobs, tax dollars, municipal services, healthy environments, good schools, access to health care, and grocery stores have followed white residents to the suburbs, leaving concentrated poverty, underfunded schools, collapsing infrastructure, polluted water and air, crime, and food deserts in segregated inner city neighborhoods.

California

In California, the federal, state, and local governments created segregation through redlining, zoning ordinances, school and highway siting decisions, and discriminatory federal mortgage policy. California’s “sundown towns,” like most of the suburbs of Los Angeles and San Francisco, prohibited African Americans from living in towns throughout the state.

The federal government financed many whites-only neighborhoods throughout the state. The federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation maps used in redlining described many Californian neighborhoods in racially discriminatory terms. For example, in San Diego there were “servant’s areas” of La Jolla and several areas “restricted to the Caucasian race.”

During World War II, the federal government paid to build segregated housing for defense workers in Northern California. Housing for white workers was more likely to be better constructed and permanent. While white workers lived in rooms paid for by the federal government, African American war workers lived in cardboard shacks, barns, tents, or open fields.

Racially-restrictive covenants, which were clauses in property deeds that usually allowed only white residents to live on the property described in the deed, were commonplace and California courts enforced them until at least the 1940s.

Numerous neighborhoods around the state rezoned African American neighborhoods for industrial use to keep out white residents or adopted zoning ordinances to ban apartment buildings to try and keep out African American residents.

State agencies demolished thriving African American neighborhoods in the name of urban renewal and park construction. Operating under a state law for urban redevelopment, the City of San Francisco declared that the Western Addition, a predominately African American neighborhood, was blighted, and destroyed the Fillmore, San Francisco’s most prominent African American neighborhood and business district. In doing so, the City of San Francisco closed 883 businesses, displaced 4,729 households, destroyed 2,500 Victorian homes, and damaged the lives of nearly 20,000 people. It then left the land empty for many years.

VI Separate and Unequal Education

Nationally

Through much of American history, enslavers and the white political ruling class in America falsely believed it was in their best interest to deny education to African Americans in order to dominate and control them. Enslaving states denied education to nearly all enslaved people, while the North and Midwest segregated their schools and limited or denied education access to freed African Americans.

After slavery, southern states maintained the racial hierarchy by legally segregating African American and white children, and white-controlled legislatures funded African American public schools far less than white public schools. In 1889, an Alabama state legislator stated, “[e]ducation would spoil a good plow hand.” African American teachers received lower wages, and African American children received fewer months of schooling per year and fewer years of schooling per lifetime than white children.

Contrary to what most Americans are taught, the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education, which established that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional, did not mark the end of segregation.

After Brown v. Board, many white people and white-dominated school boards throughout the country actively resisted integration. In the South, segregation was still in place through the early 1970s due to massive resistance by white communities. In the rest of the country, including California, education segregation occurred when governments supported residential segregation coupled with school assignment and siting policies. Because children attended the schools in their neighborhood and school financing was tied to property taxes, most African American children attended segregated schools with less funding and resources than schools attended by white children.

In 1974, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed this type of school segregation to continue in schools if it reflected residential segregation patterns between the city and the suburbs. In part, as a result of this decision and other U.S. Supreme Court decisions that followed, many public schools in the United States never integrated in the first place or were integrated and subsequently re-segregated.

California

In 1874, the California Supreme Court ruled that segregation in the state’s public schools was legal, a decision that predated the U.S. Supreme Court’s infamous “separate but equal” case, Plessy v. Ferguson, by 22 years.

In 1966, as the South was in the process of desegregating, 85 percent of African American students in California attended predominantly minority schools, and only 12 percent of African American students and 39 percent of white students attended racially balanced schools. Like in the South, white Californians fought desegregation and, in a number of school districts, courts had to order districts to desegregate. Any progress attained through court-enforced desegregation was short-lived. Throughout the mid- to late-1970s, courts overturned, limited, or ignored desegregation orders in many California districts, as the U.S. Supreme Court and Congress limited methods to integrate schools. In 1979, California passed Proposition 1, which further limited desegregation efforts tied to busing.

In the vast majority of California school districts, schools either re-segregated or were never integrated, so segregated schooling persists today. California is the sixth-most segregated state in the country for African American students. In California’s highly segregated schools, schools mostly attended by white and Asian children receive more funding and resources than schools mostly attended by African American and Latino children.