by Jamel Walker

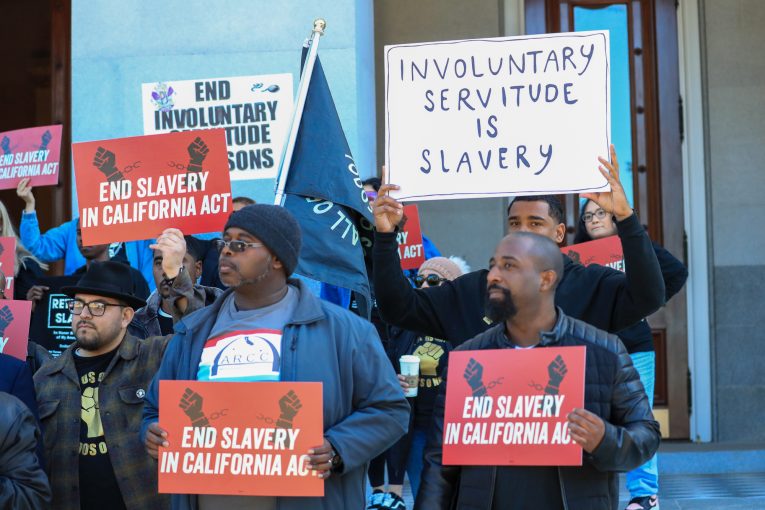

You probably thought that this country abolished slavery 150 years ago. Sadly, this is not quite true. Currently, California Legislators are debating whether it is cost-effective to end slavery in California. Introduced in February 2023 by Assembly Member Lori D. Wilson (D-Suisun), Assembly Constitutional Amendment 8 (ACA 8), known as the “End Slavery in California Act” will definitively abolish the last vestige of slavery in the Golden State’s Constitution. California Constitution, Art. 1 § 6 permits incarcerated citizens to be placed in a state of involuntary servitude. “Slavery is prohibited. Involuntary Servitude is prohibited except to punish crime.” (Cal Const. Art. 1, § 6)

Why this exception? More on that later. Surprisingly, this is not the first attempt to remove this repugnant exception from California’s Constitution. A previous bill introduced in 2022 failed to garner the requisite two-thirds vote in the Legislature that would have permitted the people of the State of California to vote on whether they wanted to remove this repugnant exception or let it stand. However, due to opposition from lawmakers on both sides of the aisle, as well as Governor Newsom’s administration, Assembly Constitutional Amendment 3 (ACA 3) died in committee on June 23, 2022.  Opponents of the bill, like former State Senator Jim Nielsen (R-Red Bluff), cite justice for victims as to why incarcerated citizens should remain enslaved during their incarceration. State Senator Steve Glazer (D-Orinda) expressed concerns removing the language could affect restitution payments, undermine our rehabilitation programs, and invite lawsuits. Newsom’s Department of Finance claimed it would cost the state $1.5 billion annually (of a $310 billion 2023-2024 budget). Proponents of removing the exception, like Assemblymember Wilson, said, “There is no room for slavery in our Constitution. It is not consistent with our values, nor our humanity.”

Opponents of the bill, like former State Senator Jim Nielsen (R-Red Bluff), cite justice for victims as to why incarcerated citizens should remain enslaved during their incarceration. State Senator Steve Glazer (D-Orinda) expressed concerns removing the language could affect restitution payments, undermine our rehabilitation programs, and invite lawsuits. Newsom’s Department of Finance claimed it would cost the state $1.5 billion annually (of a $310 billion 2023-2024 budget). Proponents of removing the exception, like Assemblymember Wilson, said, “There is no room for slavery in our Constitution. It is not consistent with our values, nor our humanity.”

If opponents are successful in killing the End Slavery in California Act, their message will be that slavery for the incarcerated is consistent with our values, as it has been since the founding of this nation.

To understand the absurdity of the California Governor’s and Legislator’s opposition to the End Slavery in California Act, it must be kept in mind that California, and ostensibly its democratic governor and legislators, are arguably the most progressive in the nation. One only needs to recall the recent actions they have taken surrounding climate change, women’s reproductive rights, immigrant rights, and the creation of a task force to study and develop reparation proposals for African Americans. Moreover, recently Governor Newsom has called for a 28th Amendment to the Federal Constitution to address the nation’s epidemic of gun violence. Yet he refuses to support an end to slavery in California’s prisons. Perhaps one could judge this statement as being hyperbolic. To illustrate that it is not, a reminder as to how we got here should suffice.

In August of 1619, a Dutch ship arrived in Jamestown, Virginia. The captain of the ship was low on rations and offered to trade his only cargo—20 African slaves. Thus began the practice of enslaving Africans in the Americas. The British colonists saw slavery as a solution to their labor shortage. In 17th century America, the colonists created an agrarian-based economy reliant upon the cultivation and exportation of cash crops such as sugar, tobacco, and rice. In order to make a profit from the labor-intensive work of the plantation system, the planters needed cheap labor. What labor could be cheaper than slave labor?

As the plantation system grew in the South, plantation owners became very wealthy in both land, slaves, and political influence. These Southern landed gentry began to receive opposition from many abolitionists in both the North and South. This opposition eventually culminated in the American Civil War.

The details of why the war was waged are not as important as what was its aftermath. Suffice it to say that leaders of the former Confederate States started the Civil War in order to continue to exploit the free labor of slaves to maintain and increase their wealth.

It has been said, “To the victor go the spoils.” To that end, on January 16, 1865, General William T. Sherman issued Special Order No. 15. The order reallocated hundreds of thousands of acres of formerly white-owned land that was confiscated for the Confederates’ treasonous behavior in waging war against the Union. These confiscated lands were located along the coasts of Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina, and were given for settlement to Black families in forty-acre plots. The order also provided for the distribution of mules to these families—thus the phrase “forty acres and a mule.” However, Sherman’s Special Order No. 15 was soon rescinded. After the assassination of President Lincoln four months later, on April 14, 1865, his vice-president, Andrew Johnson assumed the office of the presidency. A Southern Democrat and former senator from Tennessee, a slave state, Johnson was one of the most racist Presidents to assume the office. Shortly after assuming office, Johnson insisted the land seized from the treasonous Confederates and given to Black families under Sherman’s Special Order No. 15 be returned. On May 29, 1865—45 days after assuming the presidency—Johnson issued his reconstruction proclamation offering amnesty, property rights, and voting rights “to all but the highest Confederate Officials (most of whom he pardoned a year later).” In his proclamation, he declared, “This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am president, it shall be a government for white men.” Feeling empowered by Johnson’s reconstruction proclamation, Ibram X. Kindi writes in Stamped From the Beginning: “Confederates barred Blacks from voting, elected Confederates as politicians, and instituted a series of discriminatory Black codes at their constitutional conventions to reformulate their state in the summer and fall of 1865. With the Thirteenth Amendment barring slavery ‘except as punishment for crime’, the law replaced the master. The postwar South became the spitting image of the prewar South in everything but name.”

On December 18, 1865, the United States officially added the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution. It reads, “Sec. 1: Neither Slavery nor Involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” (US Const. Amend. XIII)

Again, why this exception? As Douglas A. Blackmon wrote in Slavery by Another Name: “The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, with the Southern economy in ruins, state officials limited to the barest resources, and county governments with even fewer, the concept of reintroducing the forced labor of blacks as a means of funding government services was viewed by whites as an inherently practical method of eliminating the cost of building prisons and returning blacks to their appropriate position in society.”

In other words, they needed the cheapest way to get former slaves to rebuild their ruined economy. How did they accomplish this? We find the answer in the exception clause of the Thirteenth Amendment. As a primary impetus for the creation of convict leasing laws and mass incarceration, there is a direct line to the current prison industrial complex in this country. With the rise of the convict leasing laws, a new term was introduced into the American English lexicon, when in 1871, the Virginia Supreme Court issued its ruling in Ruffin v. Commonwealth:

“For a time, during his service in the penitentiary, he is in a state of penal servitude to the state. He has, as a consequence of his crime, not only forfeited his liberty but all his personal rights except those, which the law in its humanity accords to him. He is for the time being a slave of the State. He is civiliter mortis [civilly dead] and his estate, if he has any, is administered like that of a dead man.”

The Virginia Supreme Court derived the source of its ruling, in part, on the exception clause of the Thirteenth Amendment. The Supreme Court Justices found constitutional support for re-enslaving Black people by labeling former slaves, whom racist Southerners unjustly incarcerated, “slaves of the State.”

Owing its membership in the Union to the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, California gained statehood in 1850. The Civil War had yet to be waged, nor was the Thirteenth Amendment ratified. This would not happen until 15 years later. Thus, states entering into the Union by authority of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 modeled their constitutions on Article Six of the Northwest Ordinance. Although California entered the Union as a free state, it has a legacy of apartheid that stretches back prior to statehood. We can find a poignant illustration of this in an address delivered by Charles Cushing, before the tenth annual convention of the California Bar Association, on October 23, 1919:

“Its hard to realize that … state fugitive slave laws were enacted and enforced in California, that … by express enactment of the legislature, no Indian or Negro was allowed to testify in a case to which a white person was a party.” In the case of People v. Hall the defendant, a white person, had been convicted of murder partly upon the testimony of Chinese witnesses. On appeal, it was contended that the testimony was erroneously admitted on the ground that the term “Indian” was used in the act in the generic sense and included Chinese as well as Indians.

This contention was sustained and the conviction was reversed. This decision was placed partially on the ground that when Columbus discovered America he imagined that he had accomplished the object of his expedition and had reached the Indies and had designated the Islanders by the name of Indians, and that the appellation had been universally adopted and extended in its use to the aborigines of Asia, as well as those of the new world. This decision represents the extreme prejudice of the age against what have been termed inferior races, a prejudice somewhat softened, but by no means absent, in succeeding years. The unreasoning prejudice and gross injustice to foreigners in the early history of California have been the subject of caustic comments by eminent writers.”

A century later, in a December 7, 2020, policy statement, Los Angeles District Attorney George Gascón stated, “The vast majority of incarcerated people are members of groups long disadvantaged by earlier systems of justice. Black people, people of color, young people, people who suffer from mental illness, and people who are poor.” Thus, California has a long history of incarcerating disadvantaged groups that predate the American Civil War and its aftermath of Black Codes, convict leasing, and mass incarceration. Whereas former Confederate plantation owners, politicians, government officials, and business interests criminalized being poor and Black in order to rebuild their economy by re-enslaving Blacks. According to Professor Kelly Lytle Hernández, California settler-colonial interests sought the elimination through incarceration of people they deemed as other. This included indigenous people, Mexican-Americans, Mexican immigrants, Blacks, and the poor. In her book, City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, And The Rise of Human Caging in Los Angeles, 1771-1965, Hernández describes why Los Angeles came to operate the world’s largest jail system and the leading site of racialized mass incarceration.

Vagrancy and public order laws were selectively used tools to accomplish this goal. For example, passed in 1850, the Act for the Government and Protection of Indians permitted the arrest of Native peoples for the crime of vagrancy “on the complaint of any reasonable citizen.” Moreover, the California Anti-Vagrancy Act of 1872 was instrumental in incarcerating the nonwhite and poor populations in California. Individuals rounded up for the “crime” of vagrancy either were auctioned off to white employers as forced labor, or faced dying in jail cells. Based on Art. 1 § 6 of the California Constitution’s allowance of enslaving incarcerated individuals, the slave labor of incarcerated peoples helped to build modern Los Angeles and other cities throughout California.

Were a Californian to research whether their state’s constitution or the Federal Constitution abolished slavery, they would find that they did not, but rather moved it from the plantation, first to the convict leasing system, and today, directly into the prison. Were one to reflect on how the white elite enacted laws to criminalize being poor, Black, or persons of color and were one to consider who has benefited—and continues to benefit—from this slave labor, one would understand why California’s governor and legislators are averse to removing the exception from the state’s constitution. As it turns out, criminalizing the poor and minorities has been a lucrative business for many since the inception of this country. This is exactly why ACA 3 did not make it out of committee so that the people of this state could vote on whether they wanted to continue to allow its incarcerated citizens to be “slaves of the state.” This will be exactly why ACA 8 may not make it out of committee as well.

The fact of the matter is there is no legitimate reason why incarcerated citizens should continue to be labeled “slaves of the state” of California. Governor Newsom’s Department of Finance claims it would cost the state $1.5 billion annually if the exception is removed from California’s Constitution thus making every incarcerated citizen eligible to be paid minimum wage. According to Samuel Brown of the Anti-violence, Safety, and Accountability Project (ASAP), the support services sector of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation generates $9 billion from the work incarcerated people are doing. There are approximately 93,000 incarcerated citizens housed in California State Prisons. Of that number, an estimated 60% are required and able to work. An incarcerated citizen earning $17/hr. @ 40 hrs. per/wk. would earn approximately $35,360. Multiplying that number by the 55,800 incarcerated citizens eligible to work, amounts to approximately $1,973,088,000. That is nearly $2 billion! That is a net gain of roughly $7 billion to state coffers.

There are other financial and human benefits. For example, current California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation regulations require those incarcerated citizens employed by the Joint Venture Program to allocate their earnings:

California Code of Regulations (CCR) 3476 provides:

(h) Wages earned by each inmate participating in a Joint Venture Program operation shall be subject to the following deductions, which shall not exceed 80 percent of the inmate’s gross wages:

(1) Federal, State, and local taxes

(2) Twenty percent of the inmate’s net wages after taxes shall be for any lawful restitution fine or contributions to any fund established by law to compensate (sic) the victims of crime.

(3) Twenty percent of the inmate’s net wages after taxes shall be for the costs of room and board which shall be remitted to the department.

(4) Twenty percent of the inmate’s net wages after taxes for allocations for support of family pursuant to state statute, court order, or agreement of the inmate. If the inmate chooses not to send money to a family, and there is no court-ordered withholding, these funds will be deposited in mandatory savings.

(i) In addition to (h) of 3476, twenty percent of the inmate’s net wages after taxes shall be retained for the inmate in mandatory savings under the control of the department.

(1) Funds retained for an inmate’s mandatory savings shall be deposited in an interest-bearing account.

Utilizing this structure, all incarcerated citizens earning minimum wage with a restitution order would each contribute approximately $7,072 per year. With the average restitution order being $10,000, it would take an incarcerated citizen approximately seven months to satisfy his restitution order. Assuming all 55,800 incarcerated citizens eligible and able to work have a restitution order, there would be an estimated payment of $351,209,664 of restitution payments each year of their incarceration. As it stands now, it would take the average incarcerated citizen making the average wage of .12 cents/hr. 24.1 years to satisfy his restitution order! Thus, despite State Senator Steve Glazer’s (D-Orinda) concerns that removing the exception from California’s Constitution could affect restitution payments, restitution fines will be satisfied in a timely manner.

Moreover, with 20% of earnings allocated for room and board, an additional $351,209,664 annually is collected. This represents a total of $702,419,328 collected by the state. Rather than being a drain on taxpayers, incarcerated citizens would contribute to the state’s tax base. With a combined state and federal income tax rate of 11%, approximately $217,039,600 in taxes would be deducted from incarcerated workers earning the minimum wage. Not only would it contribute to the tax base, but paying a minimum wage would contribute to the California economy based on the ability of an incarcerated citizen to make purchases from local vendors. Finally, the human benefit in an incarcerated citizen’s ability to contribute to the financial stability of their households, rather than being a drain on them, is immeasurable. There would be a decrease in the demand for public funds for low-income households. There would be an increase in the psychological well-being of the entire family because of the pride and resulting increase in self-esteem an incarcerated parent would have for contributing to the financial health of their family.

For these reasons, and many more, California government leaders should pass ACA 8, and the people of the state of California should vote on it next November 2024. If they do, they would be following in the footsteps of seven states: Vermont, Oregon, Nebraska, Colorado, Utah, Alabama, and Tennessee —two former slave states—who had the courage to remove this last vestige of the American version of apartheid.