In our past two articles, we have talked about:

- The failure of our planning process (largely due to Measure J/R/D) and its consequences.

- The failure of the single family suburb form factor of housing, and why we need to be thinking very differently about how we build our cities.

Based on the comments in the last two articles, and some of the Vanguard’s commentary in between, it is clear to us that density is a term that some Davisites fear, and misunderstand.

One commenter last week accused us of wanting to “Manhattan-ize” davis. Other people use terms like “packing people in like sardines.”

These kinds of hyperbole are unnecessary, however, because, while density is a key metric in better city planning, the levels of density we are talking about for Davis are in no way extreme. In fact, we already have a number of properties in our city with the kind of density we are advocating for.

So let’s talk about density directly for a moment, before we get into the details of alternative visions for our peripheral development. Let’s get comfortable with what density means, why it is important and why YOU might want denser development in these new Davis neighborhoods as well, even if you don’t live there yourself.

Most people probably recognize in concept many of the advantages of denser housing:

- Denser housing, by definition, uses less land than detached, single-family housing—farmland and open space is preserved.

- Denser housing, such as duplexes, townhouses, and apartments, have fewer exterior walls per unit to lose or gain heat through, so they use less energy to heat and cool than detached houses. Using less energy is better on the pocketbook and better for the environment.

- In Davis, denser housing commands lower prices than detached single-family houses, and so is more likely to be occupied by our school teachers, university staff and students—23,000 of whom are currently commuting here every day.

- Housing more of our in-town workforce would reduce Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT), traffic and associated emissions due to commuters.

- And sufficient density could support more public transit, further reducing traffic from inner-city trips as well.

One of the key things that we think many people who live in low density suburban neighborhoods (like most of Davis) don’t understand or appreciate is that density can create very attractive and desirable places. One of the most positive attributes is walkability; the ability to move around on foot and gain access to amenities that are close together.

If you love our downtown, you already know exactly what we are talking about: An environment where there are shops and restaurants within walking distance of each other.

What do we all dislike about downtown? The traffic and the parking.

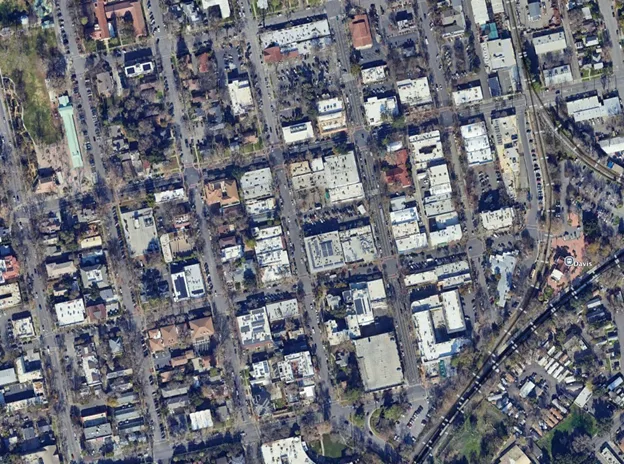

Here is an aerial photo of our downtown. It is walkable, and that is its greatest attraction.. The stores are all clustered together and there isn’t a lot of space devoted to parking. You can see from Central Park to the Amtrak station in this image, including all of our favorite restaurants and shops in between.

Now compare that to the Costco shopping center in Woodland at the exact same scale

You can always find a parking spot relatively quickly in a place like this, but we still complain when we can’t find a spot close to the door don’t we?

You can always find a parking spot relatively quickly in a place like this, but we still complain when we can’t find a spot close to the door don’t we?

Can we all agree that Davis’ downtown is a far nicer place to be than the Costco parking lot? And that lower density in general doesn’t mean it’s going to be a more attractive place?

The difference between these two shopping districts is density, which for our downtown’s sake translates into “walkability,” which itself is a synonym for “planning for people – not parking.”

No question, there is a built-in conflict. You simply cannot provide “ample parking” and maintain walkability. The parking, by definition, always pushes everything apart and destroys walkability. These two desires will always be in tension. It is a fundamental tradeoff.

Just to drive this point home, here is a picture of downtown Houston in the 1970’s at the peak of that city’s commitment to providing “ample parking.”

In their desire to make room for cars, Houston bulldozed most of their downtown.

What “walkability” means for housing

The walkable city in its idealized form looks something like this:

- You can walk from your front door to a local shop to buy a large percentage of your everyday needs:

- Anything not within walking distance of your front door can be accessed by getting onto a bike, or taking transit and then walking from the transit stop to your destination.

Experience with cities like this around the world demonstrates numerous advantages for their residents; their housing and transportation costs are less, the air is cleaner, and their carbon footprint is at least half that of their suburban counterparts. Arguably, they are healthier due to more walking and no less happy—perhaps even happier on average by being more connected to their neighbors, as many large-lot American suburbs are disconnected, lonely places.

But to make it work, you need “adequate levels of density” all around.

- If you want local shops close to your home to be viable, there needs to be enough households within walking distance (generally recognized as ¼ mile) to support them.

- If you want to take transit instead of driving, that transit needs to drop you off within that quarter mile of your destination, or people will elect to drive instead.

Density is the essential factor that makes walkability possible. Dense enough for local retail, dense enough downtown, and dense enough to provide enough ridership for the transit system to be effective.

We simply cannot be a sustainable city without embracing some levels of housing density.

But here is the good news: Walkable cities do not need to be like Manhattan or Hong Kong to provide the benefits listed above. In fact, they don’t even need to be as dense as a lot of cities that people think are indeed very nice: Paris / Madrid / Rome / Vienna / Amsterdam, etc.

In fact, it turns out that a reasonable average density target for a walkable neighborhood is only 20 units per acre (gross).

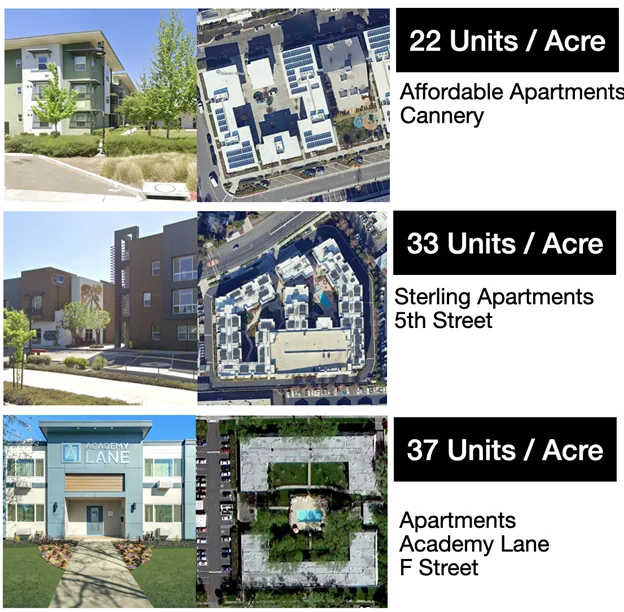

Most of us don’t have a great feel for what a given statistic of units per acre looks like, but as it happens Davis contains numerous properties on both sides of that density, and we can use these examples to visualize an average of 20 units per acre. We’ve assembled a tour: take a look and see what you think:

Single Family Neighborhoods:

Attached Housing: Condos and Townhomes

Apartment Complexes

Future Projects Coming to Downtown

Blending for 20

As we hope you noticed from the above gallery, we already have many areas of our city that are as dense, if not denser than 20 units per acre. This target need not be unfamiliar or even scary to any existing Davisite.

Having an average density of 20 units per acre is easily achievable through producing a combination of apartments and condos along with other less dense property types, including townhomes and duplexes. And there is no cause to worry whether there are developers willing to build these kinds of housing, or if they will be occupied. All of that is already happening in our city at this very moment. Obviously, they pencil out.

The key is to do this intentionally. While we already see many of these kinds of denser properties here in town, they have not been placed in a deliberate fashion or planned in combination with transit and shopping centers in order to create the walkable / transit connected neighborhoods that otherwise might have been possible.

It’s not that we want Davis to be denser than it already is. What we want is for moderate density to be well planned—considered not just as a stand-alone development, as is happening now, but as a part of the whole of the city. And that means deliberately planning for transit and bike connectivity, ensuring that the density is co-located with that transit plan, and incorporating mixed-use commercial into these neighborhoods as well.

These are not things that we are going to get via the vote-as-they-come-up Measure J process, and so it is our hope that by advocating for more sustainable and CONNECTED city design, we can inspire the developers or the city, to engage in a better process for developing these neighborhoods.

What is next:

Now that we have discussed the need for “sufficient density” in our housing supply and explored what that term means, the next topic we want to discuss is the need for pre-planned transit and bike infrastructure and how it is critical for the vision of a sustainable Davis.

After that, we will be able to consider the evaluation of some alternative concepts for Village Farms, Shriners and the rest of the Mace Curve.

Until then, we wish our fellow Davisites the warmest of seasons greetings and wishes for a prosperous new year!

The Davis Citizens Planning Group.

One omission in an otherwise sterling article: safety. The myth is that density leads to crime. The opposite is true. Density means there are “eyes on the street,” and crime diminishes. Per-capita Manhattan crime is lower than (per-capita) suburban Phoenix. Unfortunately, there’s been a war on collective action and public ownership, and those have to be elevated to keep denser communities safe. The “public realm” is paramount since the public park stands in for the private park sprawl has in each yard. With enough dense housing, communities will dedicate themselves to handling public health and safety issues like homelessness rather than building bread-and-circus projects like pro sports arenas (looking at you, Sacramento).

You would be surprised how many Davis residents shop at Costco and in Vacaville, Sacramento and online. The Davis Collection will make Davis retail slightly less awful. PetSmart will just relocate.

Do any members of the Davis Planning group live in the kind of housing they advocate for and claim is superior ?

Elmwood Drive is a good example of the tensions in this discussion. It is very likely the coolest, most comfortable neighborhood shown, with the cleanest air and least ozone, because of the wonderful canopy of mature Zelkova trees shading nearly every bit of asphalt. In planning for a hotter future, walkable will literally mean “shaded.” High-density residential areas will be the hottest, more open neighborhoods planted with shade trees will be the coolest. In a heat wave, where would you prefer to be walking?

Here are the densities of the different parts of the Village Farms proposal, based on numbers from November.

Village Farms (Nov 2024) units/acre % of units

Single-family market rate (680/157.4) 4.32 38%

Single-family starter (310/40) 7.75 17%

Townhomes (160/16.1) 9.94 9%

Condos/stacked flats (150/15.1) 9.93 8%

Multi-family affordable (60/5.9) 10.17 3%

Apartments market rate (200/11.6) 17.24 11%

Multi-family high-density (240/7.9) 30.38 13%

total (1800/254) 7.09

Comparing neighborhoods:

Central Davis (incl Elmwood)

% canopy 47.9%

CO2 equiv storage $ 2774.1

CO2 equivalent sequestration t/yr 6527

Village Homes

% canopy 27.8%

CO2 equiv storage $ 1888.5

CO2 equivalent sequestration t/yr 4443

Downtown

% canopy 24.3%

CO2 equiv storage $ 1132.3

CO2 equivalent sequestration t/yr 2664

See your own neighborhood here:

https://landscape.itreetools.org/maps/benefits/

Note that there is a walkability index in the options.

Don, we are on the same page in terms of valuing the presence of ample tree cover in our neighborhoods.

What I would point out is that density is not inversely related to canopy cover. Density, if anything gives designers the option to preserve and increase canopy cover.

If you look at the options above, the 8 unit density we see in the cannery as an anchor… there the insistence on the single family form-factor indeed means there is no room for trees.

I really dont think we should be building ANY single family homes denser than 6 units per acre for exactly that reason.. the “yards” are functionally useless, there is no room for trees… you might as well have those be townhomes… and if you did make them townhomes, you could leave some room in the land budget for trees.

Witness the 7 and 9 unit townhome examples given above… similar densities to the cannery houses, but because those are attached housing forms, suddenly you see room for trees in those images.

The amount of tree cover that is present is really just up to the architects and city planners. Plenty of very dense cities feature street trees that also cover all of the asphalt… here is a good example:

https://www.deeproot.com/wp-content/uploads/stories/2016/12/Billie-Grace-Ward_Flickr.jpg

Street trees like that have many many upsides, from protecting the sidewalks for pedestrians to reducing heat island effects… im probably preaching to the choir here…

A more extreme example perhaps from my own history: I did a high school exchange program to Moscow Russia back in the early 90’s and the apartments There have full park in the middle of the block.

Here is a link to the google map of the block in question: https://maps.app.goo.gl/nZzHD67xTNhV7akZA

Look at all those trees… THAT neighborhood is 80 units per acre!

Now, I do not advocateto be building soviet “kruschovi” type project housing… but if you look at that link, it makes the point pretty clear… you CAN preserve a LOT of tree cover while having a dense city, if anything density is a great way to reserve land allocation to preserve green space.

Tim, It’s important to emphasize that street width can be a tree shade killer: Look at most of Mace Ranch (where most trees are planted far from the curb, also meaning that they will take years longer to form any kind of canopy)… and Bretton Woods, where a canopy is essentially impossible on most streets.

More about cooling via design: Orientation of buildings to maximize cooling from prevailing winds is an important consideration, as is the relationship with trees and south facing windows etc. We need to de-emphasize the use of insulation and double glazing and solar panels to mitigate these issues.

Really looking forward to the transport chapter:

* Our regional high capacity public transportation situation is marginal, and isn’t going to magically improve as denser projects are built. People without car parking at home will obviously disproportionately be those working or going to school on UC Davis campus — That’s okay but they will be constantly looking at workarounds due to the lack of trains. People with car parking at home will use their cars because the region prioritizes cars. These people will commute outside of town, and expect to park on the way home. Where will they all park Downtown?

* 102 to Woodland: Corridor of death.

* Any high quality bicycle connectivity between peripheral projects and Downtown and campus requires extensive removal of street parking along the entire route (though possibly just one side at a time if pairs of parallel streets such as J and L only have a protected bike lane on one side to facilitate north or south travel… Though I’m not sure turning collector streets into bicycle arteries is the best solution along the whole route if we are interested in overall slowing and livability.

And if we need high quality public transportation corridors, where will they go? This is just as important as cycling… And two-way travel on the same streets such as F Street are perhaps more important for the former.

Can these two forms share the same street? Kick out the street parking and make room for both?

***

Also, in regards to “penciling out”, I would like to see a chapter on economic interests besides those of developers: Car dealers, tire repair, gas stations, Woodland megastores… Do they have influence on the situation?