On March 2, 2012, Edward Lee Elmore was released from prison in South Carolina for a crime he had not committed. But in order to do so, he had to agree to what is known as an Alford Plea – a plea arrangement in which he maintained his innocence but agreed the state could re-convict him of murder in a new trial.

On March 2, 2012, Edward Lee Elmore was released from prison in South Carolina for a crime he had not committed. But in order to do so, he had to agree to what is known as an Alford Plea – a plea arrangement in which he maintained his innocence but agreed the state could re-convict him of murder in a new trial.

However, after serving on death row for nearly 30 years, after being convicted and sentenced to death in 1982 for the sexual assault and murder of an elderly woman in Greenwood, South Carolina, it was time to get out of prison even if it meant no exoneration.

According to press accounts, “The state’s case was based on evidence gathered from a questionable investigation and on testimony with glaring discrepancies. Elmore’s appellate lawyers discovered evidence pointing to Elmore’s possible innocence that prosecutors had withheld.”

State officials initially claimed that critical evidence had been lost. That evidence included a hair sample collected at the crime scene.

After being tested for DNA, the evidence suggested an unknown Caucasian man may have been the killer. In February 2010, Elmore was found to have intellectual disabilities and thus was ineligible for execution; he was taken off death row.

In November 2011, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit granted him a new trial because of the prosecutorial misconduct in handling the evidence. The court found there was “persuasive evidence that the agents were outright dishonest,” and there was “further evidence of police ineptitude and deceit.”

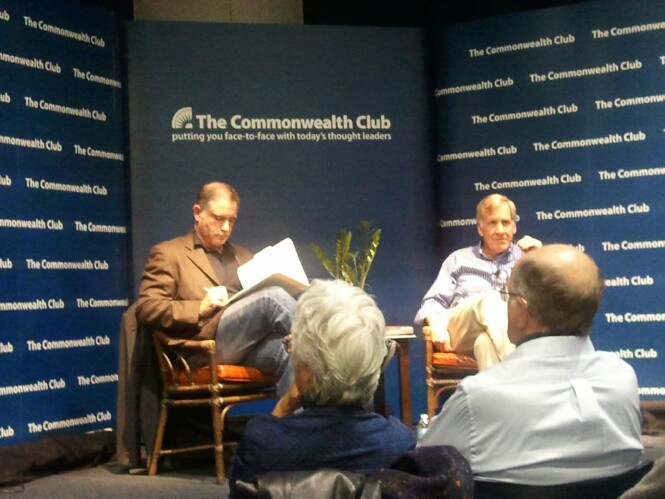

Mr. Elmore is the subject of a book by former New York Times reporter Raymond Bonner. As I have indicated previously, we saw him speak in San Francisco on March 9.

In his March 2, 2012 Op-Ed in the New York Times, entitled “When Innocence Isn’t Enough,” Mr. Bonner wrote, “On Friday, Mr. Elmore walked out of the courthouse in Greenwood, S.C., a free man, as part of an agreement with the state whereby he denied any involvement in the crime but pleaded guilty in exchange for his freedom. This was his 11,000th day in jail.”

“The state concealed evidence that strongly pointed to Mr. Elmore’s innocence and introduced damning evidence that appears to have been planted by the police,” Mr. Bonner writes.

The scary part is how difficult it is to get released even with exculpatory and exonerating evidence.

“Headlines and news stories about men being released from death row based on DNA testing suggest that this happens often,” Mr. Bonner writes. “But it doesn’t. Once a person has been convicted, even on unimaginably shaky grounds, an almost inexorable process – one that can end in execution – is set in motion.”

He adds, “On appeal, gone is the presumption of innocence; the presumption is that the defendant had a fair trial. Not even overwhelming evidence that the defendant is innocent is necessarily enough to get a new trial.”

“Due process does not require that every conceivable step be taken, at whatever cost, to eliminate the possibility of convicting an innocent person,” Justice Byron R. White wrote for the majority in a 1977 case, Patterson v. New York.

In other words, Mr. Bonner writes, “Innocence is not enough.”

As. Mr. Bonner told us at his talk in San Francisco, he stumbled on this case almost by accident. During the 2000 campaign, George W. Bush told Tim Russert his confidence “that every person who had been executed or placed on death row in Texas under his watch was guilty and had had a fair trial.”

This led him to reporting in Texas, and expanding from there.

“It was an eye-opening experience. But no case grabbed me like Mr. Elmore’s. It stands out because it raises nearly all the issues that shape debate about capital punishment: race, mental retardation, a jailhouse informant, DNA testing, bad defense lawyers, prosecutorial misconduct and a strong claim of innocence,” Mr. Bonner writes.

He writes, “Few men on death row are without any connection to the crime for which they are condemned to die. Their conviction might be reversed after an appellate court finds they were denied due process or didn’t receive a fair trial.”

However, in the case of Mr. Elmore, he became convinced “beyond a scintilla of a doubt that he had nothing to do with the Greenwood woman’s death. His conviction resulted primarily from a rush to judgment – and flagrant prosecutorial misconduct.”

“I know what I want the outcome to be on this one,” he told us in San Francisco with the kind of passion and emotion one would not normally expect to see with a veteran journalist – too often jaded by their lengthy experience. In fact, he acknowledged and even embraced the fact that he’s very passionate on this one.

He said that the book had something to do with Mr. Elmore’s release from prison. The prosecution read it and decided that they wanted to settle.

“None dare call it justice. He was forced to plead guilty to a crime he didn’t commit to get out of prison after 30 years,” he said angrily. “I want a federal investigation into the police and the prosecution because I’m telling you, they lied! I say that without any reservation.”

“They claim to have found, for example 53 pubic hairs on the victim’s bed,” he said. “53, first of all is a Guinness Book of Records [audience laughs hysterically]. I’m serious, the most you ever find at a rape scene is about eight or ten.”

As he wrote, “During his opening statement, the prosecutor, William Townes Jones III, a courtroom legend, said that 53 hairs had been gathered from the victim’s bed, where the sexual assault supposedly took place, and that most were the defendant’s pubic hairs. It was the only physical evidence that put Mr. Elmore inside the house at the time of the crime.”

A juror told Mr. Bonner that is what convicted Mr. Elmore.

But he argued, contradiction appeared from the outset.

“When Mr. Jones called an agent from the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division, or SLED, as a witness, he handed him a plastic bag marked State Exhibit 58 and asked him if it contained “53 hairs gathered from the bed of the deceased,” Mr. Bonner writes.

But the total count was actually 49 and there only 42 in the bag because seven had been taken out for examination.

Mr. Elmore’s lawyers however would make nothing of this discrepancy during their cross-examination of the investigator, or in their closing argument.

“The state’s own inability to agree on how many hairs were found wasn’t the only suggestion of foul play,” he writes. The bigger problem is the failure to secure the evidence. He writes: “State Exhibit 58, the baggie with the hairs, wasn’t sealed. Which means that the hairs could have been put in by anyone at any time, and could have included those yanked from Mr. Elmore’s groin at the police station after he was arrested.”

The bed was barely featured in the police investigation and the investigators had taken nearly a hundred pictures of the house. But, Mr. Bonner notes, they took “no photos of the bed where they claimed to have found hairs.”

However, “The state argued that, while the police might have made some mistakes, none served to deny Mr. Elmore any of his constitutional rights. The hearing judge adopted the state’s arguments verbatim and declined to grant Mr. Elmore a new trial.”

There was a single hair found on the victim’s abdomen and it was identified originally by the doctor as “Negroid” hair.

That hair disappeared.

“When Mr. Elmore’s lawyers began searching for it, state officials repeatedly said they couldn’t find it. The lawyers persisted and, 16 years after the trial, found Item T – in Earl Wells’s filing cabinet, where the state attorney general’s office conceded it had been all along,” Mr. Bonner writes.

The new examination showed that, in fact, that hair was not “Negroid,” but rather Caucasian.

“Mr. Elmore’s lawyers had the hair DNA-tested. It wasn’t Mrs. Edwards’s, which suggested it was from an unknown man, likely the killer,” Mr. Bonner writes.

This was in 2000 and it was expected that he would gain a new trial from this. But the judge ruled against him stating, “One hair is not enough.”

Writes Mr. Bonner, “Spectators gasped. But the South Carolina Supreme Court agreed.”

However, Mr. Elmore’s attorney would not give up and they got the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, the most conservative circuit in the nation, to agree to order a new trial.

Writes Mr. Bonner, “In a 163-page opinion, the majority was searing in its criticism of the SLED agents and the police.”

To reiterate, there was “persuasive evidence that the agents were outright dishonest,” and there was “further evidence of police ineptitude and deceit,” Judge Robert Bruce King wrote.

As Mr. Bonner writes, “None can call it justice.”

Far from it, and unfortunately it is an indictment on our legal system. The worst part is still the fact that most cases do not even have a small amount of physical evidence such as a hair. For those people, they may be consigned to death or life in prison for crimes that they did not commit.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

“Far from it and unfortunately it is an indictment on our legal system. The worst part is still the fact that most cases do not even have a small amount of physical evidence as a hair. For those people, they are likely consigned to death or life in prison for crimes that they did not commit.”

One case indicts our entire system? Most capital cases don’t even even have as much as a single strand of hair of evidence? Most people charged with capital (or other life-sentence serious charges) are innocent?

With the absolute lack of evidence you require to indict a whole system, I’m glad you’re not a DA investigating me. And the way you require almost no evidence–joining your pre-existing presumption of guilt–and just a couple untrue generalizations to convict, I’m really thankful you’re not on my jury.

[quote]But in order to do so, he had to agree to what is known as an Alford Plea – a plea arrangement in which he maintained his innocence but agreed the state could re-convict him of murder in a new trial.[/quote]

IMO, the Alford Plea is nothing more than a mechanism to assure the state will not have to pay the victims of wrongful convictions…

It does not, however, mean the defendant is innocent. In fact, the defendant is making an affirmative statement that he acknowledges the state has plenty of evidence to prove/reprove him guilty beyond reasonable doubt. It doesn’t suggest anyone involved in the proceedings says he’s innocent.

It’s a little like a settlement where no one has to lose face by admitting any wrongdoing. In this case, Mr. Elmore discredits the charge that there was inadequate evidence (the lonely, but profuse, hairs) to convict him–or even to reconvict him with the evidence still available that still could be used against him–by his Alford plea. It’s more like a plea bargain than anything else. He gets to walk after doing time; the state doesn’t have to prove anything over and (as Elaine points out) doesn’t have to defend itself against any wrongful prosecution claims.

It’s a mistake to make much of this. Mr. Bonner gets a book and, likely, speaker fees for a few years. But, it doesn’t say anything about actual guilt in this case and it certainly shouldn’t be used as an indictment of our legal system.

“One case indicts our entire system? “

No but this case embodies problems from the entire system.

“Most capital cases don’t even even have as much as a single strand of hair of evidence?”

Of physical evidence that can be falsified.

“Most people charged with capital (or other life-sentence serious charges) are innocent? “

Fortunately not. But enough are to call into question the veracity of the system.

“it doesn’t say anything about actual guilt in this case and it certainly shouldn’t be used as an indictment of our legal system. “

There is strong evidence that he did not do it. And I disagree, it should be used as an indictment against our legal system.

“IMO, the Alford Plea is nothing more than a mechanism to assure the state will not have to pay the victims of wrongful convictions…”

Also I think it fails to hold those responsible accountable for their actions. They still get their conviction.

“It does not, however, mean the defendant is innocent. In fact, the defendant is making an affirmative statement that he acknowledges the state has plenty of evidence to prove/reprove him guilty beyond reasonable doubt. It doesn’t suggest anyone involved in the proceedings says he’s innocent.”

He’s basically taking a lower plea to get time served. Now since he has already been convicted of a capital crime – why would the prosecutor allow that? Because he knows that the guy is not guilty of the capital crime.

The guy is innocent, but there were politics and other factors that led to the ultimate decision.

I agree with Justsaying that it is not clear that the defendant was innocent, from what DMG has presented above.

It would appear that the evidence and the case, however, were severely bungled and tainted; and so on that basis his release appears to be justified. That is, it appears there is reasonable doubt as to his guilt, so it is appropriate that he is released. Reasonable doubt is not the same as innocence. I don’t see how innocence is demonstrated beyond a shred of any doubt from the info. presented above; it seems to me that the bungled, possibly tainted evidence and possible prosecutorial misconduct entails reasonable doubt of guilt, not innocence.

I need the assistance from a lawyer in understanding this.

“That is, it appears there is reasonable doubt as to his guilt, so it is appropriate that he is released. Reasonable doubt is not the same as innocence”

My understanding is that in our legal system, one is innocent until proven guilty. Further, to be proven guilty, one must be found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. If one had been found guilty, but it was subsequently found to be on lies, or mis conduct , or tainted evidence, would that not cast a reasonable doubt. And if there were now reasonable doubt, then he should not have been found guilty in the first place. So if wrongfully found guilty in the first place, and reasonable doubt exists, how does this not equate to innocent until found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt?

It’s real simple. Once you are convicted, reasonable doubt goes bye-bye. There is no more presumption of innocence and the only thing that can gain release is evidence of innocence.

What do we have?

We have one peace of evidence that linked the man to the murder scene and that was the presence of pubic hairs which appear to be planted.

There is no other evidence he was there.

And there was a hair found that was not his or the woman’s in question which would appear to be exculpatory that the prosecution tried to cover up.

You cannot prove he didn’t do it, but there is no longer any evidence that he did it.

David

“It’s real simple. Once you are convicted, reasonable doubt goes bye-bye. There is no more presumption of innocence and the only thing that can gain release is evidence of innocence. “

I don’t doubt the veracity of this, but it does seem like something out of Alice in Wonderland to me.

Can you, or anyone else, explain to me legally/ historically how we got to such an apparently warped perception ( to me) of reality ?

Medowman: Fascinating question. The notion of innocence until proven guilty goes back to English law though not codified in any formal law. In our system, the jury is the finder of fact and make the determination of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Once that is established, in the eyes of the law, the individual is guilty. The only way that can be changed is through evidence of innocence. Even as a practical matter, it seems that you would not want a system that issues forth a new trial every time there is new evidence of doubt. Where I think the system falls apart is that there are too many entities that have too much stake in the original outcome. This comes back to the problem that the prosecutor’s goal should be not convictions or guilt but justice. Justice means that the guilty get punished appropriately and the innocent go free. Innocent in our system are those for whom guilt cannot be established beyond a reasonable doubt.

[quote]My understanding is that in our legal system, one is innocent until proven guilty. Further, to be proven guilty, one must be found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. If one had been found guilty, but it was subsequently found to be on lies, or mis conduct , or tainted evidence, would that not cast a reasonable doubt. And if there were now reasonable doubt, then he should not have been found guilty in the first place. So if wrongfully found guilty in the first place, and reasonable doubt exists, how does this not equate to innocent until found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt? [/quote]

The problem I think is that people (particularly the commenters above) are conflating actual innocence with legal innocence. The two things can be entirely different. Let me explain. A defendant charged with a crime is legally innocent until proven guilty. He may or may not have committed the crime, but he is presumed to be legally innocent of the crime charged, bc he has not been proven guilty. Once the defendant is found guilty, he is presumed guilty of the crime. Once found guilty, in order to overturn a verdict, the general standard is as follows:

[quote]A litigant who files an appeal, known as an “appellant,” must show that the trial court or administrative agency made a legal error that affected the decision in the case. The court of appeals makes its decision based on the record of the case established by the trial court or agency. It does not receive additional evidence or hear witnesses. The court of appeals also may review the factual findings of the trial court or agency, but typically may only overturn a decision on factual grounds if the findings were “clearly erroneous.”[/quote]

See [url]http://www.uscourts.gov/FederalCourts/UnderstandingtheFederalCourts/HowCourtsWork/TheAppealsProcess.aspx[/url]

There is a very high hurdle to overcome the presumption of guilt. Does that make sense?

Except that I’m not conflating actual innocence for legal innocence. Name one piece of evidence that ties the defendant to the murder?

[quote]Except that I’m not conflating actual innocence for legal innocence. Name one piece of evidence that ties the defendant to the murder?[/quote]

Whether this person is actually innocent or not is irrelevant to my discussion. The person in question was found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt and is presumed guilty. To have his verdict overturned on appeal, he must show there was legal error that effected the decision in the case based on the trial record established at trial, a high hurdle to overcome. Furthermore, the appellate courts will tend to give trials courts a lot of deference. I stated no opinion on whether I thought this defendant was actually innocent or not. I have no idea, and would not presume to say based on the fact pattern given above…

ERM,

Thanks for the clarification; interesting.

In all cases where the verdict is overturned on appeal; is the defendant considered to be (legally) ‘exonerated’? Or is exoneration a more stringent subclass of overturned verdicts?

ERM

“The problem I think is that people (particularly the commenters above) are conflating actual innocence with legal innocence. The two things can be entirely different.”

Thanks foe the excellent explanation . And you were absolutely right about my misconception. It had never occurred to me that in a system that we consider to be “just” there could possibly be a difference between “factually innocent” and “legally innocent”. I accept that it is the case, but confess that I am profoundly disappointed that we uphold such tortured reasoning in a system with so much power over lives. Makes me wonder how I could have been so naive for so long.

“The guy is innocent, but there were politics and other factors that led to the ultimate decision….Except that I’m not conflating actual innocence for legal innocence. Name one piece of evidence that ties the defendant to the murder?”

Elaine’s explanation shows the utter futility of spending much time arguing whether someone is guilty. Since only one person knows whether he did the deed–and he can’t be trusted to tell the truth or even know (if he’s crazy) whether he really did something or why–we’ve set a very high standard for a bunch of people like us to make the judgement.

David’s explanation of why we can’t ignore a jury’s guilty finding every time some minor evidence question comes up is a good one–the system would collapse if it took so little to disregard a jury’s careful work in a trial. If the evidence is serious enough to have kept the jury from arriving at a fair decision, that calls for another trial.

It seems like a good way to decide something so important in a human world that cannot be perfect. What could be better or fairer? (This probably won’t be helpful to someone who knows, but compare it to making decisions about withholding medical care. Seems as though that would be another case where perfect decisions are impossible so we come up with a continuously “improving” process of what we think is the best may humanly possible.)

We’ve come up with a method that lets off guilty people so the we can be surer that innocent people don’t get convicted. We don’t want people running around breaking laws we’ve set up to have a workable society, but it’s more important to us to be fair to the innocent than to get all the guilty punished.

In this case, the person was found guilty. He states that there still is enough untainted evidence to find him guilty again now. Since David reports he was granted a new trial, one has to wonder why he didn’t want to go through with it.

Since he agrees that the state has the evidence to convict him again, that certainly would make one pause before wanting a retrial. It’s quite a stretch to contend that he lied in his plea, given the circumstances reported in this case.

With the plea in hand, the prosecutor can figure justice is served, even without trying him again, partly because he’s done time, because retrying him wouldn’t guarantee a guilty verdict, and whatever other rationale he had. It doesn’t mean the person is any less guilty than he was when the jury determined he was guilty in the first place.

Even with questions being raised about some of the evidence–aren’t there always questions raised?–that doesn’t mean there wasn’t or isn’t enough for a jury to convict beyond reasonable doubt.

The difficulty in dealing with demands like David’s (“Name one piece of evidence….”) is that the defendant and prosecutor have agreed to forego another trial so we won’t see–more importantly, a jury won’t see–the evidence the current prosecutor has. David has the luxury of claiming the guy is innocent, but there’s less basis for saying that than for saying he’s guilty (which, of course, he is).

I don’t think you should be dismayed or profoundly disappointed to realize we’ve come up with the best we can at this point and that we improve it as technology and other knowledge advances. Like in medicine?

JustSaying

“I don’t think you should be dismayed or profoundly disappointed to realize we’ve come up with the best we can at this point and that we improve it as technology and other knowledge advances. Like in medicine?”

I would agree with your comments, except for one critical difference. Medicine is not based on a structurally adversarial system.

Alrhough it is true that there are frequently differences of opinion in the best way to proceed, the goal of everyone involved is the best outcome for the patient. In the legal system, if one side “wins” the other side “loses”. I think that when careers and compensation are at stake, it is too much to ask to assume that every one will play fair and be completely honest and forthcoming. I don’t believe that we have come up with the best that we can. I do not believe that our adversarial system is the best that we can do.

Like in fee for service medicine where doctors may be tempted to do more than is necessary for the patient, or to schedule more appointments than are necessary in order to collect additional fees, I feel that our adversarial legal system may tempt some to with hold information, or even lie, in order to have their side “win” thus advancing their personal interests. Do you believe this doesn’t happen in the judicial system ? I know for a fact it does in medicine. I rather doubt that lawyers as a group are either more or less driven my moral/ethical considerations than are doctors.

[quote]ERM,

Thanks for the clarification; interesting.

In all cases where the verdict is overturned on appeal; is the defendant considered to be (legally) ‘exonerated’? Or is exoneration a more stringent subclass of overturned verdicts?[/quote]

From: [url]http://www.wisegeek.com/what-are-overturned-convictions.htm[url]

[quote]Overturned convictions are convictions in criminal cases which are later set aside, reopening the cases under discussion and exonerating the person who was originally convicted. Worldwide, wrongful convictions are a problem in many penal systems and it is difficult to obtain accurate estimates of the number of people who have been wrongfully convicted. This is in part because not everyone can afford the appeals process and as a result some people who have been convicted in error have never had an opportunity to challenge the conviction.[/quote]

But see: [url]http://www.wtnh.com/dpp/news/crime/appeal-to-begin-for-once-exonerated-conn-convict[/url]

[quote]Appeal to begin for once-exonerated Conn. convict

Updated: Saturday, 17 Mar 2012, 1:14 PM EDT

Published : Saturday, 17 Mar 2012, 1:14 PM EDT

ROCKVILLE, Conn. (AP) – A Connecticut man whose murder conviction was overturned but later reinstated is going back to court for his second appeal trial.

Fifty-year-old George Gould’s habeas corpus trial is set to begin Monday in Rockville Superior Court.

Gould and co-defendant Ronald Taylor served more than 16 years in prison for the killing of New Haven grocery owner Eugenio Deleon Vega in 1993. Both men were freed in April 2010 when a judge in the first appeal trial declared them innocent, but the state Supreme Court overturned that ruling last July and ordered a new trial.[/quote]

Something happened with the formatting, so just ignore the blue letters – it should be black…

And ignore the repeated info in the middle!!!

ERM–thanks for the info.; and interesting situation with Gould–just because you’re exonerated doesn’t necessarily mean they system is done with you for the (alleged) crime!

I had a feeling I didn’t know enough about medicine to suggest a comparison. You’re right about the adversary nature of the legal system; of course, it’s critical to making it as fair as it is. But, never mind about my analogy; it was just to suggest that even doctors and medicine aren’t perfect.

There are many rules to limit the concerns you have. The defense, which has the advantage by not having to prove anything, likely withholds and lies as a matter of course and doesn’t care about “justice,” just getting acquitted. I’m assuming you aren’t suggesting the defense has any obligation be forthcoming, as long as they follow the rules that guide the trial.

The state better not get caught breaking the rules, although they sometimes do. Prosecutors have built-in incentives that keep them from cheating in order to win–their careers and compensation aren’t enhanced by winning if they ever get caught cheating so the risk to their success and personal interests is much higher than you are assuming.

Some have suggested every defendant could have their guilt determined by a judge or a panel of judges. Not adversarial, but would you want professional judges deciding (considering they’re part of of the state)? So, fighting it out in front of people who are more like me seems like a pretty good right to have if I’m charged with a crime. Not perfect, but I can’t think of a better way.