Local Critics Believe Yolo County Could Do Better in Allocating Funding and Changing Current Incarceration Strategies –

Local Critics Believe Yolo County Could Do Better in Allocating Funding and Changing Current Incarceration Strategies –

Back in January, the Yolo County Board of Supervisors approved a plan that would apply for a 148-bed jail expansion as part of a plan to increase capacity in the face of AB 109.

Supervisor Don Saylor was the lone dissenter of this plan. He argued that the current needs assessment ended its projection in 2007. The 2007 needs assessment projected continued growth in the jail population. But what we have learned with actual data since then is that the Average Daily Population (ADP) has not increased since 2008 but dropped from 428 to 384.

He further argued that first-time bookings have fallen 25 percent, from 3200 per year to 2400 during that period.

“If we’re not facing the need to submit an application tomorrow, January 11, for construction or not, we wouldn’t be doing this proposal without updating that needs assessment,” Supervisor Saylor said, “because really from 2008 to 2011 we’ve seen reductions in the ADP and we’ve seen reductions in bookings, in particular first bookings have declined by 25%.”

On Wednesday, the ACLU of California released a statewide analysis of realignment.

In their press release they write: “The decisions counties are making right now about how to implement realignment will have dramatic and long-lasting impacts on public safety and on local taxpayers.”

However, their 100-page report “finds that many counties have yet to embrace a central charge of the realignment legislation: to implement evidence-based practices, including alternatives to incarceration, that are proven to prevent crime, limit future victims and stem the flow of people who cycle through our jails and prisons.”

The new report, which is based on an in-depth review of all 53 available county realignment implementation plans, finds massive new investment in jails with much less funding allocated to proven crime-prevention programs such as mental health services and drug treatment.

“Simply building new jails or re-opening unused jail space treats the symptom but not the underlying disease,” said attorney Allen Hopper, director of the Criminal Justice and Drug Policy Project of the ACLU of California and co-author of the report. “It’s time to confront the fact that in California, over-incarceration is itself a disease, and the way to end it is to expand the use of mental health services, drug treatment and job training, and to reserve prison and jail for responding to serious crimes.”

Central to the ACLU’s analysis is the stunning fact that most people in county jails have not been convicted of a crime. More than 71 percent of the 71,000 Californians held in county jails on any given day are awaiting their day in court. Most of them do not pose a risk to public safety but are stuck behind bars because they simply cannot afford bail.

And while much of the conversation about realignment has focused on jail overcrowding, the ACLU argues that counties can significantly lessen the problem by adopting a pre-trial assessment tool to identify individuals who can be safely released on their own recognizance.

The report also finds:

- a promising commitment – though not yet realized – by many counties to adopt alternatives to incarceration and evidence-based practices to reduce recidivism;

- a troubling lack of state monitoring, data collection, outcome measurements and funding incentives to help counties successfully implement realignment; and

- paradoxically, under the current funding formula, a financial reward for counties that have historically incarcerated more people for low-level offenses.

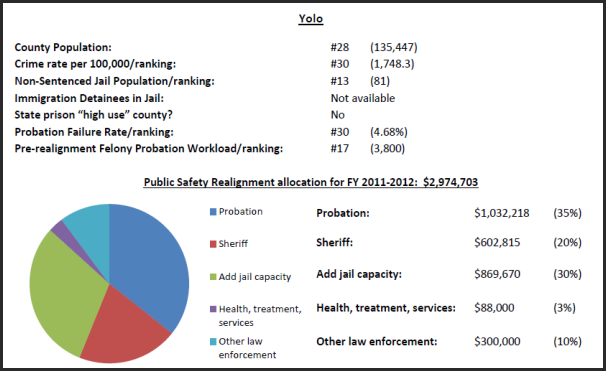

Yolo County is one of the county plans the report analyzes.

According to the report, Yolo County’s plan “makes allocations that don’t fit into the categories we created; $82,000 was allocated to the District Attorney and Public Defender, above and beyond the separate earmarked state allocation for District Attorney and Public Defender activities. This results in categorized amounts shown in the profile chart totaling less than 100% of the Public Safety Realignment allocation amount.”

The data actually understates the problem when it argues that it is not a prison high-use county. As the Vanguard noted last year, that is only due to the relatively low population overall.

According to the data, there are 3.95 persons in prison from Yolo County per 1000 people ages 18 to 64. While Yolo County ranks 20th (out of 30) in crime rate among counties with over 100,000 population (ages 18 to 64), it ranks 4th in the prison rate.

To put that into perspective, Yolo County ranks higher in the rate of people in prison than Fresno (9), San Joaquin (10), Solano (13), Sacramento (15), Los Angeles (16), San Diego (17), and Alameda (24).

The ACLU report notes that, on jail expansion, “The County will increase jail capacity by hiring staff to support 30 unused beds in the Leinberger facility. Another option contemplated in the plan is supplementing a federal contract for the use of 25 additional beds.”

They further note, “The County applied for and was denied $30,000,000 in AB 900 Phase I funds. The County more recently applied for $42,225,000 in Phase II funds.”

The ACLU report also analyzed alternatives to incarceration.

Pretrial: No. Management of the pretrial population is not specifically discussed in the plan. It is unclear whether the alternatives to incarceration currently employed by the Sheriff and Probation, such as home detention and GPS monitoring, will be used for individuals awaiting trial.

Sentenced: Yes. The Sheriff will expand the use of home detention with electronic monitoring for sentenced inmates. The Sheriff currently screens sentenced inmates for mandatory victim restitution, community service and work incentive programs.

Post release community supervision: Yes. Probation currently conducts needs assessment of individual supervisees in developing a case management plan. The department also utilizes cognitive behavioral therapy, residential substance abuse treatment, drug testing and alcohol monitoring, a system of graduated sanctions for PRCS [Post-Release Community Supervison] violators, and electronic and GPS monitoring, and assists in operating the County’s Drug Court. Other evidence-based practices such as telephone reporting and restorative justice programs are contemplated in the plan, but not supported in the budget.

Locally, there is a good deal of criticism of the county’s spending priorities. Supervisor Saylor has been a perhaps surprising leading critic of the county’s plan.

“What concerns me is that, of the $3.3 million that we initially allocated,” he said back in October, “only $88,000 of that was designated for mental health.”

“This is not about how we can be soft on crime,” Don Saylor said in dissent to the county’s plan. “It’s about how we protect public safety in the long term. I don’t feel we’re there, the budget is not what I hoped it would be and I’m not going to support it.”

Bob Schelen, chair of the Yolo County Mental Health Board, told the board, “The budget as it is currently written should be rejected because there does not appear to us to be enough money for treatment programs, for job training programs, and for a number of other programs that are important to the entire process of realignment.”

The plan and program, he argued, was balanced, but the dollars do not reflect that balance.

“We need to put the dollars into the innovative programs that we think would be helpful for this realignment program,” Mr. Schelen added.

“The reason why we’re here,” said retired Public Defender Barry Melton, “is that the state prison system blew it and didn’t spend adequate resources on health and mental health.”

Critics such as Bob Schelen, who serves on the Mental Health Board, are concerned about the lack of money being put into mental health programs.

“In Yolo County, we only have anecdotal evidence of how the plan is affecting our county jails at this time. At present, there has been at least one case where a prisoner being transferred did not receive the proper mental health care,” Mr. Schelen wrote in a Vanguard op-ed in January.

“Often overlooked in the discussion of realignment is recognition and understanding of the basic criminal justice reform strategy that underlies the legislation. The legislature explicitly found that criminal justice policies that simply rely on building and operating more prisons “are not sustainable and will not result in improved public safety,” he said.

He argued, “We need to break free of the belief from 35 years ago that there is no way to change offender behavior or reduce recidivism. Evidence-based research shows that interventions can work, but they must target those offenders that present the greatest risk of offending again and those individual characteristics that are changeable and predictive of further criminality.”

“We know that there are people that need to be in prison or jail. No one is disputing that,” he said. “However, a real concern under the pre-realignment status quo is that prisons were becoming de facto mental health facilities. This cannot be allowed to continue under realignment, and it looks like Yolo County is taking steps in the right direction on this issue.”

The ACLU’s plan puts forth recommendations, as well.

“California is far from the only state experiencing the confluence of fiscal crisis and prison overcrowding. But realignment has created a unique opportunity to take California’s public safety policies down a new path,” they write.

Much of their concern is with the issue of how pre-sentenced in-custody defendants are handled – which has been an issue we have raised previously and we will examine more closely in the coming days or weeks.

Included in their recommendations are mandating data collection and analysis, revising the realignment allocation formula to “incentivize counties to reduce recidivism and increase use of cost-effective alternatives to incarceration, particularly for the pretrial population.”

They also recommend enacting statewide front-end sentencing reforms to expand county flexibility to manage jail space and to support successful reentry.

They further recommend amending statewide pretrial detention laws “to keep behind bars only those who truly pose a risk to public safety while increasing the number of people released on their own recognizance.

They argue in favor of discouraging further county jail expansions and construction plans, halting or reducing such plans, and look into funding “concrete plans for community-based alternatives to detention for both the pretrial and sentenced populations.”

They argue: “Research and experience clearly point toward the factors that successfully reduce re-offending by people at risk for repeat petty crime and for cycling in and out of jail: housing, employment, drug and alcohol treatment, mental and physical health care and other stabilizing influences.”

Their report concludes that California is at a crucial crossroads:

“At best, counties will meet realignment with a commitment to reducing over-imprisonment, to protecting public safety, and to wisely allocating limited resources. At worst, counties will react to realignment as a mere transfer of authority over bodies – and simply incarcerate people convicted of non-serious, non-violent offenses at the local level now that cannot be shipped off to state prisons. Despite spending millions of taxpayer dollars on jail expansion, those counties will quickly see the same inexorable overcrowding and high recidivism rates that the state prison system has produced.”

—David M. Greenwald reporting

David

Thanks for covering this very important topic for our county. I hope you will be able to include a cost comparison between incarceration, home detention with GPS, and release on their own recognizance for those not yet convicted in future reporting.

I am also amazed at the discrepancy in the allocation of funds with 10 times as much being allocated to incarceration as to preventative programs. And this at a time when, at least in the field of medicine we have overwhelmingly developed an appreciation of the cost effectiveness of an evidence based, preventative model of care. While I am seeing, in this blog, in my office, and in my life in general,, from individuals all across the political and cultural spectrum a steadily increasing awareness of the need for prevention rather than after the fact attempts to “cure”, that does not seem to have reached the awareness of our county law enforcement or leadership with the exception of Supervisor Saylor.