By Robb Davis

By Robb Davis

Allow Local Jurisdictions in California Some Latitude in Setting Local Speed Limits – I recently had the opportunity to take a course offered by the League of American Bicyclists entitled “Traffic Safety 101”. I am an experienced cyclists but I took this introductory course to better equip me to work with children in Davis on bicycling safety. Part of the course involved practicing various skills on an active roadway in Roseville, CA.

I do not know Roseville well and had never cycled there. Parts of Roseville are “poster children” for the concept of sprawl.

The city features wide, multi-lane boulevards, a large and spread out set of shopping destinations and, because it sits astride Interstate 80, several large on/off-ramp “cloverleaf” areas. Our practice cycling took place in one of the shopping districts around I-80.co

We practiced things like “taking the lane”, merging with traffic to make turns, and avoiding the dangers of poor road design (yes, most non-cyclists don’t understand that a road designed for cars can be terribly dangerous for a cyclist – and not just because of speed).

As an experienced cyclist I don’t get nervous in too many riding situations. But the practice ride through Roseville was very disquieting for me.

It was not only no fun, it was at turns challenging, nerve wracking and downright scary. Merging to make turns was daunting and there were several times when I nearly needed to stop my bike because I was approaching my turn but could not get a car driver to allow me to merge into the traffic flow.

In analyzing the experience afterward it became clear that a key problem was that the speed differential between the cars and bicycles was simply too great. But it was not just the speed differentials. I routinely cycle CR99 and the speed differentials on that road are much greater than those in Roseville. It is not uncommon, for example, to be pedaling along at 15-17 MPH and have cars whizzing by at 55-65 MPH. While not the most enjoyable riding, the differentials are not too troubling. The reason is that on a rural road a cyclist does not need to make many bicycling maneuvers.

In contrast, to get around Roseville (or any suburban or urban environment) to do the normal kinds of activities cyclists need to engage in – shopping, running errands, commuting, going to meetings – requires using an array of bicycling maneuvers: turning frequently and changing lanes a considerable amount. In such environments speed differentials matter much more because of the need to interact with traffic much more. Cyclists need to “negotiate” with auto drivers on a regular basis in order to get where they need to go.

Now imagine you are NOT an experienced cyclist. How much more daunting might speed differentials be to you? Even if traffic levels are not as high as in Roseville, might you not be discouraged from riding if you were not comfortable with your ability to make a turn in front of and across traffic because of the speed differentials? Recent research indicates that cyclists avoid roads with high traffic intensity (a combination of volume and speed) and routes that require them to make frequent left turns.[1] In correspondence with one of the authors about the research I raised the question about whether speed differentials discourage people form choosing the routes that require left turns. While the author acknowledged that the research field is too recent to demonstrate that conclusively, she did note that my “hypothesis about left turns is accurate.”

In Davis we have mode share goals that suggest we will want to increase bicycle ridership as a proportion of all trips up to 30-35% (or higher) in the coming decades (we are probably at 25%). We have already reached the “low hanging fruit” in terms of ridership, though that “fruit” must be viewed through the lens that we are one of the most “bike friendly” cities in the US.

We have achieved this mostly through investment in bike lanes and bike paths, which provide riders with a separate space in which to ride. We have also done it by designing our cul de sacs with access to greenbelts, which makes most neighborhoods accessible to cyclists, by developing high cost bits of critical bike infrastructure such as bike bridges and tunnels, and by providing ample bike parking at key destinations.

But the low hanging fruit harvested with these important measures has all been harvested. To go further we must address the potential riders who refuse to use the infrastructure we have. Laying down more infrastructure is going to get us only marginal gains. To increase ridership (again, as a proportion of all trips) we are going to have to coax new riders or more hesitant riders onto the road for more reasons. And to do THAT, we need to deal with the issue of speed.

The problem is that Davis does not fully control the enforceable speeds it sets in the city. The city can post any speed limit it wants (with a few exceptions like around schools) but it does not do so because it cannot enforce the speed limit if the street’s “critical speed” is too high. In other words, if we wanted to we could post a speed limit of 15 mph on every street.

However, people ticketed on many such streets could not be compelled to pay their fines if they contested them. This is because the state requires the city to assess the “critical speed” on streets (or, more correctly street segments – not including neighborhood streets).

The critical speed is the speed that 85% percent of drivers actually drive on the street. Cities (and counties) have a bit of leeway to set speed limits below that – 5 mph – without justification, based on the latest California law. What this means is that if the critical speed is 30 mph on a street, the City can post and enforce a speed limit of 25 but could not enforce one of 20 mph.[2]

Actions to reduce speeds to a lower enforceable level are called “traffic calming” and there are many methods used to achieve calming. The problem is most are costly and some are onerous to cyclists and cars (think speed bumps or tables). The problem with many of Davis’ streets is that they are simply far too wide.

I am not talking here about neighborhood streets but our “feeder” and “arterial” streets. Wide streets, laid out in a grid with few stops, invite higher speeds. This pushes up up “critical speeds” and creates a situation in which greater differentials exist between bikes and cars.

City-wide traffic calming is prohibitively expensive and it may make much more sense to focus on changing car driver behavior to achieve lower speeds. We could do this through public education campaigns or through placing temporary speed estimators on streets to remind drivers of their speeds. Or, if we were allowed, we could use speed limits to change behavior.

Currently, of course, we have no power to use this particular approach for reasons noted above. It is for that reason that I would like to launch a legislative initiative in the state of California that would return a limited amount of control to California’s cities to set enforceable speed limits that enable them to achieve critical community goals. I know nothing about writing legislation but my proposal would look something like this:

Each local government jurisdiction (city or county) in the state will be permitted to unilaterally set enforceable speed limits on select “safety corridors” not to exceed XX% of total street/road miles. Such corridors must be signed so as to alert drivers to their special status with special speed limits posted with special status signs.

The purpose of these “safety corridors” is to enable jurisdictions to promote alternative transportation uses that will be more effectively employed if traffic speeds are lowered. Such corridors are expected to have the effect of promoting increased walking and biking for all street users and reduce the incidence of injury or mortality caused by car/pedestrian or car/bicyclist collisions.

The exact proportion indicated by the XX% above will need to be developed. The issue of signage is critical to this proposal because creating new “signage” is no small feat, given that the federal and California-specific Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices (CA MUTCD) specifically mandates signs that can be used on state roads and streets. It is not feasible to go outside the manual and create new signs. Fortunately, the CA MUTCD has a set of signs that could be adapted for use in these new safety corridors:

These numbers refer to the CA MUTCD and, combined with standard speed limit signs, could provide the special signage necessary to alert motorists that they are in a special zone. These signs were developed to accompany a federal program that permits states (in California through the California Highway Patrol) to adopt special safety rules such as the requirement to use headlights in the daytime in areas with an elevated level of accidents – especially deadly ones. It would seem uncontroversial to use such signage as a “preventive” measure.

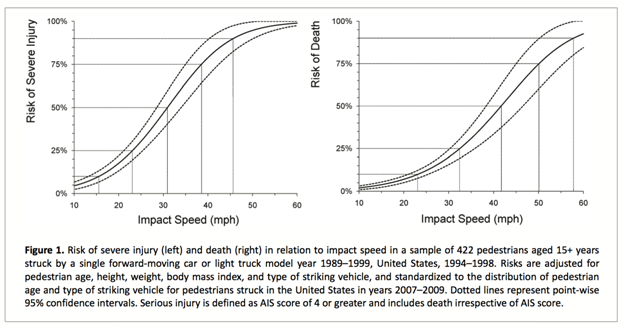

Keep in mind that reducing speed limits where there is much mixing of pedestrians and cyclists with cars makes sense from an injury (and mortality) reduction perspective. The following chart[3] shows the relationship between car speed and injury and death when cars hit pedestrians.

Another study[4] summarizes this in its abstract:

This research explores the factors contributing to the injury severity of bicyclists in bicycle-motor vehicle accidents using a multinomial logit model. The model predicts the probability of four injury severity outcomes: fatal, incapacitating, non-incapacitating, and possible or no injury. The analysis is based on police-reported accident data between 1997 and 2002 from North Carolina, USA. The results show several factors which more than double the probability of a bicyclist suffering a fatal injury in an accident, all other things being kept constant. Notably, inclement weather, darkness with no streetlights, a.m. peak (06:00 a.m. to 09:59 a.m.), head-on collision, speeding-involved, vehicle speeds above 48.3 km/h (30 mph), truck involved, intoxicated driver, bicyclist age 55 or over, and intoxicated bicyclist. The largest effect is caused when estimated vehicle speed prior to impact is greater than 80.5 km/h (50 mph), where the probability of fatal injury increases more than 16-fold. Speed also shows a threshold effect at 32.2 km/h (20 mph), which supports the commonly used 30 km/h speed limit in residential neighborhoods. The results also imply that bicyclist fault is more closely correlated with greater bicyclist injury severity than driver fault.

The point here is that if we can reduce speeds on certain key streets-those leading to schools or to key activity centers[5]-to 20 mph or below we not only encourage more riding but we also reduce the probability of injury and death to very low levels. At this time, neighborhood streets have speed limits of 25 mph but many culs de sac and short streets keep speeds down, and in the downtown core frequent stops keep speeds down. However there are no feeder or arterial streets with critical speeds that would permit the posting of an enforceable 20 mph speed limit.

If California law allowed us to reduce speed limits on a limited number of streets we could reduce bike/car speed differentials, encourage more cycling by less experienced or confident cyclists while reducing the potential for injury in the case of collisions.

Robb Davis is a League of American Bicyclists Certified Instructor, a member of the Board of Davis Bicycles! and Vice Chair of the City’s Bicycle Advisory Commission. In March he and his wife will celebrate a decade of living “car-free”. The views expressed in this piece are Robb’s alone and do not reflect the opinions or positions of any of these three entities. Robb will try to be available throughout the day to respond to questions concerning this article.

[1] Broach et al (2012) “Where do cyclists ride? A route choice model developed with revealed preference GPS data” Transportation Research Part A 46:1730-1740.

[2] There is a bit more to the story than given here and I would be happy to share more specifics for those interested.

[3] Tefft, Brian C. (2011) Impact Speed and Pedestrian’s Risk of Severe Injury or Death. Washtington: AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety.

[4] Kim et al (2007) “Bicyclist injury severities in bicycle-motor vehicle accidents” Accident Analysis and Prevention. 39:238-251

[5] The City’s Transportation Advisory Group will be recommending a street classification of “primary bikeways” that could be used to prioritize key streets for calming.

“20 mph or below”?

I think 25 mph is already slow enough.

Thanks for this information Robb.

My experience – being both a driver and a bicyclist in this town – is that there is little to no speed limit enforcement in Davis. And I have wondered why. We used to have a traffic officer (or two) on motorcycles but they seemed to have disappeared.

I’d like to suggest that the PD start enforcing the speed limits . The City could certainly use the revenue. And it would certainly make for a safer experience for bicyclists

“The problem with many of Davis’ streets is that they are simply far too wide.”

I agree. Another reason to support narrowing the streets are the planning implications of streets that are far too wide. Given our community desire to avoid sprawl, perhaps our scarcest resources is the land supply. Yet we squander our supply with massively wide streets, medians and setbacks. In some of the subdivisions the buildings appear to be 200 ft. apart. Are we planning our streets and subdivisions for Roseville’s community vision or Davis’ vision?

-Michael Bisch

And how about the pedestrian experience on these massively wide streets? We speak frequently of human scale in our community dialogue pertaining to development. Where is the human scale in the design of some of these streets? It’s like walking through a giant surface parking lot, not much to enjoy!

Another technique we use to kill the pedestrian experience in our subdivision design is to turn the homes away from the street, worse yet, turn the homes away from the street AND build tall walls between the neighborhood and the street. These gated/security subdivsion designs are hardly conducive to the pedestrian experience or for building community on which we pride ourselves so highly.

-Michael Bisch

Rob wrote:

> Keep in mind that reducing speed limits where there

> is much mixing of pedestrians and cyclists with cars

> makes sense from an injury (and mortality) reduction

> perspective. The above chart[3] shows the relationship

> between car speed and injury and death when cars

> hit pedestrians.

I’m all for pedestrian and bike safety (as a guy who has been hit by cars walking and riding). I wonder how they got the speed in the 422 accidents in Rob’s graphs since most times when a pedestrian is hit the pedestrian says “he came out of nowhere going 50mph+ and the driver says I was driving no more than 20mph… I’m seriously wondering if we call the Davis PD that we can think of even one accident in recent years where the driver and pedestrian that was hit agree on the car speed (or an accident where a cop had a radar gun on a car that hit a pedestrian)…

Just quickly (and David assures me he is going to fix the graphics that are missing/misplaced above):

Michael: The reality is that the streets of most concern (B Street, segments of Villanova and Loyola, for example) are already built. We cannot undo the width and narrowing the travel lanes via various calming techniques would be costly. However, your points are well taken.

South of Davis: The study from which the graph is taken is open source from AAA and can be found here:

[url]https://www.aaafoundation.org/sites/default/files/2011PedestrianRiskVsSpeed.pdf[/url]

You will note that much of the data on speed comes from scene reconstruction and an imputation process where only estimates were available. We obviously have very few fatalities or even serious injuries in Davis related to vehicle/ped or vehicle/bike crashes (though we have had a few recently). The main point of my piece is that lower speeds provide more comfort to the less experienced cyclist and that injury/mortality reduction is an additional benefit of lower speeds IF crashes do occur.

I will come back to rusty49’s point later if I have time. Not that I disagree rusty49 but there are some key streets posted at 25 in Davis that are out of compliance and we cannot ticket people for surpassing that limit. I will try to provide a couple of examples later.

SOD: I assume you are being a bit facetious on the speed point, after all they have ways to estimate speeds by looking at skid marks and stop times.

To attempt to address (but maybe not answer) SouthofDavis’ question… the answer to the methodology may be in the studies cited by Mr Davis… one way, particularly on the fatal crashes may be investigation of skidmarks either prior to or immediately after the POI [point of impact]… I believe that the science is pretty strong, but you’ll notice the “banding” of the data, which gives a measure of ‘confidence level’. Besides speed variables include the age, size, and health of the victims… a strong, healthy, young male has a better chance of surviving a given speed crash than a 90 year-old woman with osteoporosis (sp?).

I respect Robb for citing his data sources… those curves are entirely consistent with data I’ve reviewed for 30+ years, and with a basic knowledge of physics… the energy absorbed by a victim is proportional to the SQUARE of the velocity of the vehicle.

We don’t need a 20 MPH or below speed limit anywhere in Davis. All we need is to have current speed limits and laws enforced for drivers and BICYCLE RIDERS.

Robb wrote:

> South of Davis: The study from which the graph is

> taken is open source from AAA…You will note that

> much of the data on speed comes from scene

> reconstruction and an imputation process where only

> estimates were available.

Thanks for the info, but I want to remind everyone that “estimates” are not a good way to find out how fast a vehicle was really going (the “speed kills” people almost always estimate higher that actual and the defense attorney “expert witness” will almost estimate lower than the actual speed). If you talk to anyone that has worked a “breaking box” at a BMW CCA or PCA driving school it is amazing how different tires will leave VERY different skid marks in the exact same model car going the exact (verified with radar) speed over the exact same surface…

Then David wrote:

> SOD: I assume you are being a bit facetious on

> the speed point, after all they have ways to

> estimate speeds by looking at skid marks and

> stop times.

I was serious since:

1. People that hit someone almost always lie about how fast they were going (as do people that are hit).

2. Unless you pay a ton of money for a scientific study that either gets the permission of the guy in the accident to re-use his car (and tires) in the study or tracks down an identical car (and identical age, brand, wear and model of tires) you just have a ballpark idea of the speed.

Then Rusty wrote:

> We don’t need a 20 MPH or below speed limit anywhere

> in Davis. All we need is to have current speed limits

> and laws enforced for drivers and BICYCLE RIDERS.

It is hard for most people to drive a car at under 25mph (and real hard to go under 20). There is a radar sign that shows every cars speed in front of the Alder Ridge Apartments (now called “The Edge”) on Cowell and just about every car that passes it is going over 25mph. Unless I am out for a shopping run on my crappy single speed (an old mountain bike without derailleurs but still has all the sprockets on the cranks and rear wheel) I am almost always going over 20 mph on my bikes…

Put up the electronic speed detection signs all over town and it will cause a reduction in speed. It is less expensive than more patrol officers.

The 55mph freeway speed limit was impractical and was not enforced. Speeds crept up only slightly when it was dropped.

The lower-than-25mph speed limit will not be enforced nor is it practical. Current speeds are not even enforced, and changing signs does not also create dozens of police to increase enforcement.

I bicycle around Davis, and its pretty good except for downtown, and the City Council has just made downtown worse by adding four stop signs, so now bicycles will avoid 3rd Street or just blast through more stop signs. Bicycles avoid obstacles.

The trick is infrastructure, and a long-term changing of driver attitudes, similar to the long-term change in racist attitudes, i.e., it does not happen overnight.

Roseville bike lanes and wide streets are indeed nightmare-ish. Sacramento City’s new bike lanes downtown have many dangerous flaw points. I tried to ride a bike in suburban Orange County once — nothing! No bike lanes, no bike culture, and an overwhelming car culture.

Live where bikes are welcome.

Frankly – I see the speed detection signs as a tool and I think Davis has added some of them that will actually provide some data on behavior. I think they can help. We need more tools.

Alan – part of why I am proposing doing this on a limited number of key streets is so we focus enforcement in those places where there is a greater likelihood of cyclists with lowers skills/experience (children in particular). I don’t think there is enough enforcement now but part of the problem is that we have too many out of compliant streets (critical speeds too high) and the police simply are not going to waste their time handing out tickets that judges will not uphold. By focusing on a few key streets/segments we can also focus enforcement.

Again, this is but one tool and it does not mean we will need more officers–because of the focus. I agree that other calming solutions would be better but they are costly. The CC tasked staff nearly two years ago to come up with solutions to calm Sycamore (north of Covell) and J Street (between Covell and 8th). To date nothing has been done though both the BAC and the SPAC provided input and recommendations.

I am proposing this as one tool.

rusty49: Here are four street segments posted at 25 for which the critical speed is too high to allow for enforcement. With a law like the one I am proposing we could enforce 25 MPH on these streets. Think about how important they are for children biking and walking to schools:

8th Street from Anderson to B Street

F Street from 8th to Covell

L Street from 5th to Covell

Loyola from Pole Line to Monarch

There are others like these.