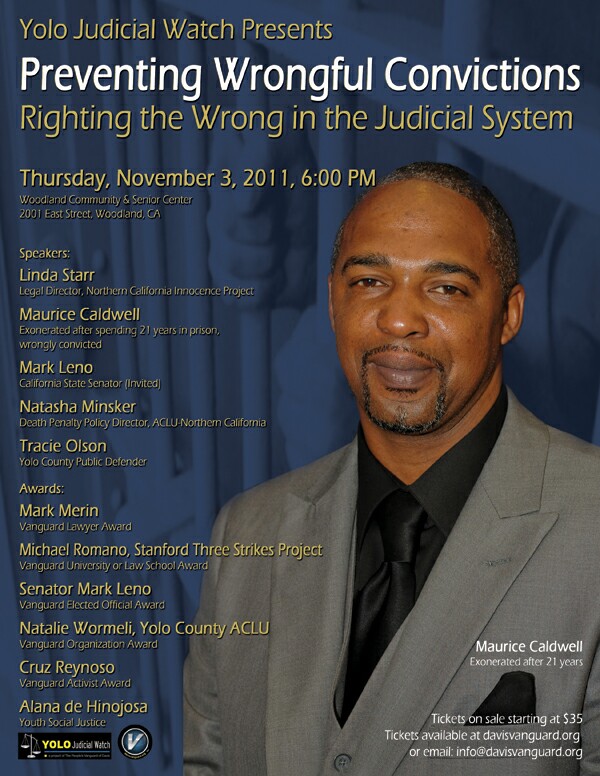

On November 3, Yolo Judicial Watch will focus its attention, at its annual Fundraiser and Awards Ceremony Event, on the issue of preventing wrongful convictions.

Maurice Caldwell, who will also speak at the November 3 event, was wrongfully convicted of a 1990 murder and had his verdict overturned last December, after spending over 20 years in prison. He was finally released this year around the first of April.

A judge set aside Mr. Caldwell’s 1991 conviction last December and ordered a new trial, after lawyers for the Northern California Innocence Project (NCIP) at Santa Clara University School of Law demonstrated evidence of actual innocence and that Mr. Caldwell’s defense attorney at trial was incompetent.

A San Francisco Superior Court judge then ordered Mr. Caldwell released when San Francisco prosecutors declined to retry him.

In September, the State of Pennsylvania received a report from the Advisory Committee on Wrongful Conviction, and while it focused ostensibly on Pennsylvania, there is much that we can learn from this very thorough and thoughtful report commissioned from the bipartisan joint state government commission.

“Since 1989, 34 states and District of Columbia have been witness to 273 postconviction DNA exonerations. These exonerations represent cases in which the conviction has been indisputably determined to be wrong by continuing advances in the use of DNA science and evidence,” the Commission reports in the executive Summary of a 328 page report that looks at the problems, what other states and jurisdictions have done about these problems, and sets for recommendations going forward.

The Commission notes: “They represent tragedy not only for the person whose life is irreparably damaged by incarceration for a crime he did not commit, but also for the victim since each wrongful conviction also represents the failure to convict the true perpetrator.”

This is a point lost on many, that the damage of a wrongful conviction is not merely to the person who is imprisoned wrongfully, losing a huge percentage of his or her life to incarceration. The wrongful conviction also casues damage to the victims.

The case of Maurice Caldwell is instructive, because not only was Mr. Caldwell denied his freedom wrongfully for 20 years of his life, but the actual perpetrator killed another innocent person before his arrest in that case – a loss of life that might have been avoided had investigators been more cautious in evaluating the evidence.

They write, “These exonerations challenge long-accepted assumptions in the soundness of certain practices of the criminal justice system both nationwide and in Pennsylvania.

They cast a disturbing doubt on the reliability of eyewitness identifications, confessions, and overly aggressive practices within the adversarial legal system.”

It is of these “overly aggressive practices within the adversarial legal system” that the day to day work of the Judicial Watch project is based on, but the bottom line is the outcome it produces, putting people through potentially unnecessary stress, putting people into the legal system who do not belong there, and potentially incarcerating people for unduly long periods of time at times for crimes that they did not commit.

The report continues, “Victims can often be mistaken in their identifications of perpetrators, especially when influenced, often unintentionally, by subtly suggestive procedures for lineups, photo arrays, and showups. Interrogation techniques applied to suspects are calculated to obtain a confession and recurrently ‘work’ against innocent suspects, especially those who are inexperienced, suggestible, unintelligent, mentally defective or anxious to end the interrogation.”

Many have suggested these are mere rare occurrences, they will cite the low frequency of exonerations compared to the numbers flowing through the judicial system.

However, we also need to understand that safeguards are not nearly as plentiful as we would like to believe. We know that “defendants have been punished for crimes they did not commit.” The report argues, however, “Compounding these concerns, biological evidence is available in only a small number of cases involving violent crimes. There is every reason to believe that mistaken identifications, false confessions, inadequate legal representation, and other factors underlying wrongful convictions occur with comparable regularity in criminal cases where DNA is absent.”

And that thought should keep us up all night, because “While it is impossible to say with confidence how many innocent people are now, have been or will be imprisoned, it would be indefensible to say that every conviction or acquittal is factually correct.”

They argue, “To this end, we must pay close attention to the lessons contained in these DNA cases. To the best of our ability, we must respond by creating practical and workable measures that serve to advance conviction integrity by minimizing the risk of error.”

The report goes on to discuss recommendations that have been and are currently being considered in a number of other states.

The report summarizes the best practices and reform efforts in other state, looking in particular at efforts from 14 states, one of which does not include California.

Yolo Judicial Watch, however, believes that one element missing from a lot of these reform efforts is the need for scrutiny and oversight in the judicial system itself. Most newspapers, as they struggle financially, have cut back on their court beat reporters.

Moreover, even when they did focus more energy on the courts, the beat reporters tended to pick high profile cases. So the Topete Trial in Yolo County has rightly received numerous daily stories from several regional newspapers and television stations.

But often the worst abuse occurs in cases which no one is watching. We watched a proceeding, for instance, on Friday where a man was charged with auto theft. Except he never stole the car. Iinstead, he was late returning it after borrowing it, which the victim claimed was without permission.

The DA was quick to point out that the statute does not require permanent deprivation of the property, it could be temporary. But the judge overruled the prosecutor, arguing that there was clearly no intention to permanently deprive the individual of their property, and therefore she dropped the case down to a misdemeanor.

The DA took the word of the “victim,” a man with a 28-year history of heroin addiction, whose memory was not completely clear, and there was substantial evidence that the defense had that the defendant had had permission to use the car, and the victim likely forgot.

Where is the scrutiny by the DA? The individual was willing to plead to the misdemeanor to end the ordeal, but could have continued to fight and win.

While this is not an example of a wrongful conviction, it is an example of the need for the public to scrutinize what is going on at the court level. Without the existence of exculpatory evidence here, who knows what would have occurred.

It is important to push for changing the way we conduct investigations, question witnesses and scrutinize eyewitness statements, because the cost is tremendous.

People will look toward the man wrongfully executed, but what Maurice Caldwell suffered is perhaps far worse. First, the wrong person lost 20 years from his life. But second, the consequence of that mistake was horrific, as another individual was killed as the result of the failure of the authorities to catch the right person.

In many ways, that is every bit as much of the ultimate cost as the wrongful execution. An innocent person is dead because of this failure.

The Northern California Innocence Project (NCIP) at Santa Clara University School of Law operates as a pro bono legal clinical program, where law students, clinical fellows, attorneys, pro bono counsel and volunteers work to identify and provide legal representation to wrongfully-convicted prisoners.

To learn about Maurice Caldwell, Linda Starr and the efforts of the Innocence Project, attend Yolo Judicial Watch’s event on November 3 at the Woodland Community and Senior Center. Tickets are available starting at $35. For additional information about sponsorship opportunities please click here.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

I think the stolen car story is an example of how the judicial system is working. The DA tries to throw the book at the defendant, the defense uses the I had permission defense, and the judge weeds through the mess and comes up with an answer.

Sure from a distance it looks like it works, except for the guy who spends periods of his life incarcerated when the DA could have made the determination himself that this was not auto theft.

“Since 1989, 34 states and District of Columbia have been witness to 273 postconviction DNA exonerations. These exonerations represent cases in which the conviction has been indisputably determined to be wrong by continuing advances in the use of DNA science and evidence,”

It seems, based on what I’ve read here and elsewhere, that the majority of the wrongful convictions occurred during times (70s, 80s and early 90s) when DNA science (for the purpose of identifying/eliminating a criminal suspect) and forensic work were virtually nonexistent and/or not nearly as advanced as they are presently. What’s more, juries were likely less inclined to treat forensic/DNA evidence as indisputable fact in the above mentioned decades as they are now (in fact, often juries expect damning scientific evidence.)

In other words, the DNA science and forensic techniques, which can now be used to clear a suspect/defendant, were not readily available when many of the wrongfully convicted were investigated, arrested, charged and ultimately convicted for their alleged crimes. (By the way, the above quote doesn’t specify precisely when the convictions occurred or what percentage of the convictions were pre-“DNA profiling,” so it’s difficult to nail down what science was available at the time of each conviction, but I believe “DNA profiling” as a technique came about in the mid 80s.)

Have there been fewer wrongful convictions this century or do we not have much data due to the lengthy appellate process?

Given the advancements in science (which will presumably continue), are we likely to see far fewer wrongful convictions in the next 10-20?

What you are seeing is a measurement issue. How did we learn about the wrongful convictions – when they were determined in court, many took two decades to resolve. Moreover, the advent of DNA testing probably reduces the numbers of the class of cases we have detected. But DNA is a small percentage of all cases, so I believe the number is a lot higher than we think.

DMG,

“What you are seeing is a measurement issue. How did we learn about the wrongful convictions – when they were determined in court, many took two decades to resolve. Moreover, the advent of DNA testing probably reduces the numbers of the class of cases we have detected. But DNA is a small percentage of all cases, so I believe the number is a lot higher than we think.”

What are the different classes?

What percentage of all exonerations are the result of post-conviction DNA/scientific analysis/evidence? I suspect that the cases where DNA or other scientific evidence cannot prove the innocence of the convicted or raise considerable doubt about his/her guilt are far less likely to result in exonerations.

For those exonerations that result from DNA/scientific evidence, the court is essentially looking at the case again, but now with incredibly powerful scientific evidence/analysis, which law enforcement, prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges and juries may have never taken into account. It could also be that this evidence was introduced and easily discountable, due to the relative newness of the science/technique.

In those cases where no such evidence/analysis exists, the convicted often has to rely on less definitive (ie less scientific) evidence that they contend points to their innocence or procedural issues that occurred at the various phases leading up to the conviction. Aren’t convictions such as these more difficult to overturn?

We know, through DNA profiling, that certain individuals could not have committed the crimes they had been convicted of 20+ yrs ago, for example. In the other cases, in which no such evidence unequivocally points to the innocence of the convicted, the judge is left with evidence that has shades of gray and/or procedural issues.

I guess what I’m throwing out here is…

1-if the vast majority of all known wrongful conviction cases were overturned due to the relatively new DNA profiling/forensic techniques; and

2-the vast majority of those arrests/trials/convictions took place at a time when DNA profiling/forensic techniques either didn’t exist, weren’t universally applied or were not advanced enough to be of much help in eliminating suspects; then

3-it could be that we see fewer wrongful convictions this century, when the presence of DNA is available, because of the developments in DNA profiling and science (the use of which is now standard in criminal investigations) can rule out innocent suspects (or acquit defendants) in the same way it has proved the innocence of so many wrongfully convicted; lastly

4-unless we see significant changes in other realms of the criminal justice system, which can then be used as a basis for the convict’s appeal, I suspect that the measurable number of wrongful convictions (year 2000- and on) will be significantly less than the number of wrongful convictions of the 20th century.

“4-unless we see significant changes in other realms of the criminal justice system, which can then be used as a basis for the convict’s appeal, I suspect that the measurable number of wrongful convictions (year 2000- and on) will be significantly less than the number of wrongful convictions of the 20th century.”

To clarify: The above assumes a drastic change would occur that throws out confessions obtained through certain interrogation tactics used by law enforcement, eyewitness identification, etc. and could be used to appeal a conviction.

Theft and Unlawful Taking or Driving of a Vehicle

CA Veh Code:

[b]10851[/b] (a) Any person who drives or takes a vehicle not his or her own, without the consent of the owner thereof, and with intent either to permanently or temporarily deprive the owner thereof of his or her title to or possession of the vehicle, whether with or without intent to steal the vehicle, or any person who is a party or an accessory to or an accomplice in the driving or unauthorized taking or stealing, is guilty of a public offense and, upon conviction thereof, shall be punished by imprisonment in a county jail for not more than one year or in the state prison or by a fine of not more than five thousand dollars ($5,000), or by both the fine and imprisonment.

Please note the statute is not auto theft or grand theft auto…

It is unlawful driving or taking…