By Gary Wells, Professor of Psychology, Iowa State University

By Gary Wells, Professor of Psychology, Iowa State University

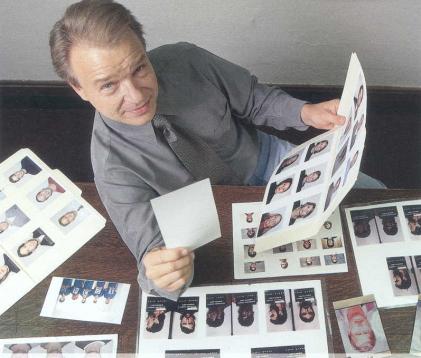

I have been conducting experiments on eyewitness identification since 1975, while I was still a graduate student in psychology at Ohio State University. Along with a fellow student, we designed this simple experiment where we staged a theft repeatedly and had people try and pick the thief out from a lineup. Not only did they make a lot of mistakes, but sometimes they were quite certain that they were right when in fact they were wrong.

After the first DNA exonerations in the early 1990s, I began to see how relevant those cases were to my research. For the first time ever, we had a litmus test that would help establish that eyewitness misidentification is not just a hypothetical problem. Before that, the work that I and other scientists were doing was largely ignored by the justice system. Many people in the legal community took the position that—“No one is actually serving time in this country for a crime they did not commit. It just doesn’t happen.” So, the DNA exonerations had the impact of getting the legal system to start paying attention to the science that we were doing.

In this area of eyewitness science we had explored a number of important factors that contribute to mistaken identifications, such as the problem of cross-racial identifications and the ways in which a culprit’s use of a weapon reduces memory for the culprit’s face. But among the most useful discoveries were finding that ways in which lineups are conducted affects the reliability of identifications that are made. This includes the instructions that witnesses are given before viewing a lineup, the quality of the fillers (non-suspect lineup members) used in the lineup, and the potential influence of a lineup administrator who can inadvertently influence the witness’s identification decision.

A number of jurisdictions began to take note of these findings and make reforms to how they conducted lineups. Other jurisdictions, however, showed some reluctance to make changes based on laboratory experiments that used simulated crimes. Accordingly, we launched an experiment with police departments in San Diego, Tucson, Austin and Charlotte using laptop computers to administer lineups in actual cases to test one of our main ideas, namely that sequential lineups (witnesses view each lineup member one at a time) would produce fewer mistaken identifications than would the traditional simultaneous lineup (lineup members viewed as a group). Unlike our lab studies, we could not be sure whether the suspected person in the lineup was in fact the culprit. But, each lineup included only one suspected person and the remaining members were known-innocent fillers. Hence, whenever a witness identified a filler, we could score that as a mistake. The Innocence Project was an important partner in this research.

The results of the study, released last year, corresponded well to what we had learned from the controlled laboratory research—that the rate of misidentification drops when witnesses view a sequential lineup. A key component was that the officer administering the lineup did not know which lineup member is being investigated by police.

The Innocence Project has been critical to bridging the gap between practices and procedures that are used by law enforcement and the social science recommendations. That’s a gap that social scientists alone cannot fully bridge, and the Innocence Project has been an incredible broker in that process.

Once law enforcement investigators are exposed to the research, they are quite receptive to it. The more lineups they’ve done in their career, the more they can appreciate the idea that there are limitations to eyewitness evidence, which they’ve observed in their own professional experience. Once they know there’s a problem, they’re eager to find a solution.

Read more about the field study.

Read more about the recent widespread reforms to eyewitness identification procedures.

Read more about Gary Wells’ research.

Originally Published by the Innocence Project – reprinted by permission.

Just an interesting tidbit on the Innocence Project:

Man freed by Innocence Project is now suspect in attempted murder. See [url]http://www.latimes.com/news/nation/nationnow/la-na-nn-alan-crotzer-attempted-murder-20120731,0,7437560.story[/url]

In regard to identifying a perp, a lot depends on how long the witness saw the perp, what the lighting was like, how far away were they from the perp, etc.

I think this type of study can be very valuable but the introduction of the Innocence Project removes ability of the study be remain unbiased.

Elaine

[[quote]Just an interesting tidbit on the Innocence Project:

[/quote]

I am not sure how you think this article reflects on the Innocence Project.

If he was innocent of the initial crimes, he should not have been incarcerated regardless of his subsequent actions when released. Surely you are not implying that The Innocence Project has some kind of crystal ball that they should have been able to see that he would commit a violent act in the future?

Perhaps I am missing your point ?

I’m missing it too because the article here is by a researcher at Iowa State, not the Innocence Project, they just were the ones that published it. So why is that point even relevant to this article on eyewitness ID?

Here’s another point that needs to be raised. The guy spent 24 years in prison. He was acculturated there. So that’s a problem – even though he was innocent. Second problem, we have stayed in contact with Maurice Caldwell, the guy is really struggling. Franky Carrillo is struggling too, but he is in a better position. The Innocence Project has been trying to raise money to be able to hire some of these guys, because they come out, many have been in prison for twenty years, some have families without much means or no family at all, they have no job skills. Franky is going to college now and educated himself in prison, but he was 16 years old. Bottom line, if he was innocent of the crime, he should be released, but it’s not surprising that this would happen.

[quote]If he was innocent of the initial crimes…[/quote]

If…

When someone is exonerated of a crime years later, and not retried for the same crime, it does not necessarily mean they did not commit the crime as a practical matter. All it means is that there is not enough evidence to support retrying them. That gets into the whole issue of the problem of retrying stale cases 20 or more years after the fact.

Elaine

So are you suggesting that if there is not enough evidence to retry, then we should not be reconsidering these cases even if the initial evidence of testimony is found to be faulty ? If this is not your position, what would you suggest ?