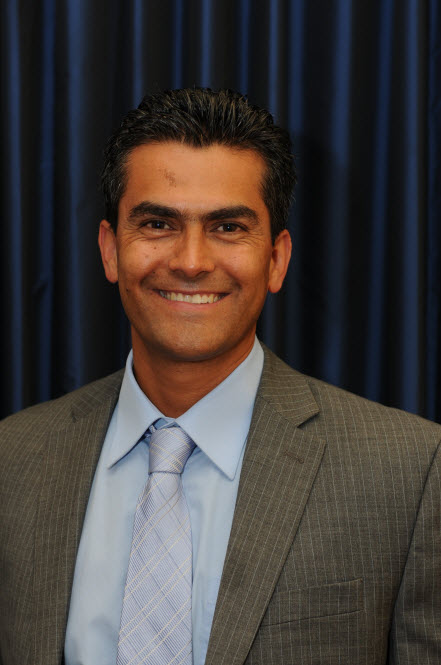

Franky Carrillo spent two decades in prison after he was convicted of a drive-by shooting in 1992 and sentenced in 1992 to one life term and 30 years to life in prison. Critical to his conviction was the testimony of five eyewitnesses who said that they saw him pull the trigger.

Franky Carrillo spent two decades in prison after he was convicted of a drive-by shooting in 1992 and sentenced in 1992 to one life term and 30 years to life in prison. Critical to his conviction was the testimony of five eyewitnesses who said that they saw him pull the trigger.

Had we known then what we know now about the fallibility of eyewitness identification, particularly under poor lighting conditions, this travesty of justice may have been avoided.

Unfortunately, combining an overzealous if not outright corrupt investigator, indifferent defense and wrongful eyewitness identification, Mr. Carillo, who will speak at the Vanguard‘s event in Woodland, ended up serving twenty years for a crime for which he was factually innocent and not present on the scene.

Due to the vigilance of groups like the Innocence Project, the Northern California Branch that helped to free Mr. Carrillo which will be honored by the Vanguard on Thursday, not only do we have people exonerated after being wrongly convicted, but we have data to show us what has gone wrong.

Research shows that eyewitnesses may get their identifications wrong by up to 25 percent of the time. It is important to understand under what conditions that is more likely to occur.

Last year, the New Jersey Supreme Court made a ruling that was aimed at resolving what they called the “troubling lack of reliability in eyewitness identifications.”

A year later, for the first time, the New Jersey courts are having judges instruct jurors in order to improve their evaluation of eyewitness identification.

The New York Times reported this week, “A judge now must tell jurors before deliberations begin that, for example, stress levels, distance or poor lighting can undercut an eyewitness’s ability to make an accurate identification.”

“Factors like the time that has elapsed between the commission of a crime and a witness’s identification of a suspect or the behavior of a police officer during a lineup can also influence a witness, the new instructions warn,” they add.

“You should consider whether the fact that the witness and the defendant are not of the same race may have influenced the accuracy of the witness’s identification,” the instructions say.

“Human memory is not foolproof,” the instructions say. “Research has revealed that human memory is not like a video recording that a witness need only replay to remember what happened. Memory is far more complex.”

Even under the best of conditions, eyewitness identification is simply not reliable. As the instructions indicate, researchers have noted that our minds do not work like tape recorders.

Writes the Innocence Project, “The human mind is not like a tape recorder; we neither record events exactly as we see them, nor recall them like a tape that has been rewound. Instead, witness memory is like any other evidence at a crime scene; it must be preserved carefully and retrieved methodically, or it can be contaminated.”

Moreover, memory is subject to contamination that is undetectable to the eyewitness. Dr. Geoffrey Loftus, a Psychology Professor at the University of Washington, is one of the foremost authorities on memory and human perception.

In his testimony as an expert witness in a recent trial, he spoke of post-event information. This is information, as its name implies, that creates a coherent story rather than the fragmented information that is initially processed. At the time, making this more coherent does not make it more accurate.

While post-event information makes it seem more “real,” the memory could actually be based on a false premise. For instance, an eyewitness may hear from someone else that the attacker wore a certain color, and subconsciously accommodate that information to his or her memory of the event.

Writes the Times, “Although it applies only in New Jersey, the ruling was widely heralded for containing the most exhaustive review of decades of scientific research on eyewitness identification.”

Moreover, experts believe that the new instructions will be influential as other state courts look at revising their approach to eyewitness identification.

“These instructions are far more detailed and careful than anything that exists anywhere in the country,” said Brandon L. Garrett told the Times. Professor Garrett is a law professor at the University of Virginia and the author of “Convicting the Innocent,” a book that includes a study of eyewitness misidentifications, which was cited by the New Jersey court in its decision.

“These instructions are far from perfect,” he added, “but they are a remarkable road map for how you explain eyewitness memory to jurors.”

Barry Scheck, who is the cofounder of the Innocence Project, called the changes “critically important,” predicting “the new instructions would not only affect how juries are instructed, but would also influence trials themselves and the evidence-gathering that precedes them, since both sides will know that such instructions will be given.”

“It changes the way evidence is presented by prosecutors and the way lawyers defend,” he said, adding, “The whole system will improve.”

“We expect juries are going to hear this evidence, so we want to give them the tools with which to evaluate the eyewitness testimony,” New Jersey Chief Justice Stuart Rabner told the Times.

Meanwhile, we can see in the example of Franky Carrillo how this might have applied.

Years after the conviction, the victim’s son admitted what investigators should have known all along – he had not seen anything.

Attorney Ellen Eggers had to lead a team of investigators out to the scene of the crime under similar lighting conditions.

Eventually she convinced the judge to go to the crime scene.

“[The reenactment] established that none of those witnesses could have seen what they claimed to have seen,” she said. This meant it was not merely adult witnesses recanting years later – there was actually evidence to support that recantation.

It was the revelation that one could not make out the facial features in the lighting conditions, coupled with Mr. Carrillo’s father’s testimony that he was at home that night, that led even the prosecution to believe that Mr. Carrillo was not the shooter that night.

“A fundamental principal in American criminal justice is that one is innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt,” writes Nancy Petro, a contributor to the Wrongful Conviction blog. “In the past two decades, DNA-proven wrongful convictions have revealed that we’ve routinely met the standard of ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’ with evidence that is quantifiably incorrect one-fourth of the time.”

“A 25 percent error rate in school has historically earned the very lackluster grade of D. A 25 percent margin of error would shutter any hospital and ground any airline,” she noted. “But, in the criminal justice system, most Americans, blinded by trust in the system and a popular allegiance to ‘tough on crime’ policies, have yet to demand best practices in securing the most accurate evidence possible from those who have witnessed a crime.”

“Responsible citizens must urge our elected officials to require best practices in the criminal justice system,” Ms. Petro writes. “Any case based solely upon eyewitness identification should raise red flags. It’s becoming increasingly obvious that eyewitness identification alone, with its 25-percent error rate, cannot prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.”

If that’s the case, more states should consider following the lead of New Jersey.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

[quote]”But, in the criminal justice system, most Americans, blinded by trust in the system and a popular allegiance to ‘tough on crime’ policies, have yet to demand best practices in securing the most accurate evidence possible from those who have witnessed a crime.”[/quote]

I would add one more factor to our willingness to convict based on questionable identification. That factor is fear. What I see reflected in many of the posts on the Vanguard and in the press in general is a not just fear of crime, but also of diversity and social change. I think that too often, a lack of understanding of the culture and values of those we identify as “the other” make us too willing to believe too quickly and easily in their guilt. Whether this distrust of “the other” is based on age ( as in disapproval of the actions of those rowdy students, or the comment “Don’t trust anyone over 30), or race, or religion, or nation of origin, I think it presents a real threat to accuracy in our court system and to the cohesiveness of our society as a whole.

[quote]Research shows that eyewitnesses may get their identifications wrong by up to 25 percent of the time.

Even under the best of conditions, eyewitness identification is simply not reliable. [/quote]

If eyewitness identification were “not reliable”, it would not be permitted in the court room – much as lie detector tests are inadmissible because they have been deemed unreliable. Apparently eyewitness testimony appears to be reliable [b]at least 75% of the time[/b]. Eyewitness testimony is imperfect to be sure, as most evidence is, and challangeable by the defense. But to make such a sweeping statement that eyewitness testimony is “not reliable” is incorrect IMO. You can certainly say eyewitness testimony [b]can be unreliable[/b], but that is a far cry from making a blanket statement that it [b]is unreliable[/b].

I have no problem with jury instructions as given in New Jersey…

As for the Carrillo case, there are not enough facts here for me to draw any conclusions, e.g. what other evidence was available at the time. I did some research – Carrillo was only 16 years old at the time of his arrest, which put him at a huge disadvantage in the criminal justice system.

“If eyewitness identification were “not reliable”, it would not be permitted in the court room”

No there were a whole bunch of forensic procedures allowed to be admissible into the courts that had no scientific basis. We have long accepted eyewitness ID, that does not mean it is reliable. The courts are now trying to get jurors to at least understand conditions under which eid might be challenged. That’s a start. A 25% error is too high to be useful without stringent guidelines. We just did not know enough of the science to question it sooner. This is a case where courts are behind the times in evidence versus science.

ERM: My understanding of Carrillo is that the DA sent their investigator to observe the crime scene and determined that the witnesses could not have seen what they claimed and so the DA did not oppose when the judge vacated the jury verdict and did not attempt to retry the case.

To dmg: No evidence or investigative technique is perfect. All evidence is unreliable to some extent, including DNA. See below. Does that mean we shouldn’t use evidence, because it is imperfect?

See [url]http://www.marymeetsdolly.com/blog/index.php?/archives/925-Unreliable-evidence-A-look-at-DNA-forensics.html[/url]

[quote]So where is the problem in this technique? After scientists analyze the DNA found at a crime scene, they compare it to the suspect’s DNA to see if their barcodes match. The more loci where the STRs match, the more likely that the DNA comes from the same individual. Typically, to make sure that the barcodes matched, labs in the United States look at 13 loci. Labs in the United Kingdom look at 10 loci. If all 10-13 loci had the same lengths of STRs, it was said that the DNA was from the same individual. The lower the number of loci, the less confidence the DNA is a match. In other words the longer the barcode, the better the identification tool.

The problem comes from the fact that most DNA from a crime scene is not perfect. It can be degraded or mixed with DNA from other individuals. Sometimes labs can only match 9 loci to the DNA found at a crime scene.

Scientists are starting to question this assumption that 10-13 loci are enough to rule out the possibility of a random match to DNA other than the suspect. In other words, if 10-13 loci are not enough to make a definitive barcode, then a 10-13 loci DNA profile can actually match more than one individual. According New Scientist, a recent look into the possibility of random matches produced some serious results:[/quote]

Or to put it another way, some evidence is reliable enough to be admitted into the court room. Lie detector tests have been deemed so unreliable, they are not admissible in court. Eyewitness testimony is reliable enough that it is permitted in court. However, the accuracy of eyewitness testimony is always subject to challenge by either side.

[quote]ERM: My understanding of Carrillo is that the DA sent their investigator to observe the crime scene and determined that the witnesses could not have seen what they claimed and so the DA did not oppose when the judge vacated the jury verdict and did not attempt to retry the case.[/quote]

All that means if the eyewitness testimony was no good. We don’t know what other evidence there was; how stale any remaining evidence was, etc. The prosecution obviously felt they could not successfully retry this case. I have to wonder where the defense attorney was in this case? Out to lunch?

Meaning the original defense attorney. Why didn’t he go to the crime scene, recognize the eyewitnesses could not have seen what they did, and challenged the eyewitness testimony on this basis?

“No evidence or investigative technique is perfect.”

Would you get into a car if you knew you have a 25% chance of dying?

“Or to put it another way, some evidence is reliable enough to be admitted into the court room. Lie detector tests have been deemed so unreliable, they are not admissible in court. “

I think part of it is that the research on lie detector tests have been known for some time while we are just finding out the fallibility of eyewitness testimony. We allowed bullet lead analysis into the courtroom at one point, we don’t any more. Science changes things.

“All that means if the eyewitness testimony was no good. We don’t know what other evidence there was; how stale any remaining evidence was, etc. “

Define we? There was no evidence linking Carrillo to the crime scene other than the eyewitness testimony.

“Meaning the original defense attorney. Why didn’t he go to the crime scene, recognize the eyewitnesses could not have seen what they did, and challenged the eyewitness testimony on this basis? “

Ineffective defense.

Re: eyewitness testimony not reliable:

Hmmm…this may account for why my wife was acting so funny last night. Perhaps she was not my wife! Tonite I will check her ID to be sure; understanding that my eyeball testimony may be unreliable.

[quote]erm: “No evidence or investigative technique is perfect.”

dmg: Would you get into a car if you knew you have a 25% chance of dying? [/quote]

Comparing driving a car to the courtroom is not a good analogy. I can give you a hundred reasons why (don’t tempt me – I’m a lawyer, I can do it! LOL). Evidence is not taken in a vacuum, it is pieced together to make a whole. It is more accurate to think of a body of evidence as a jigsaw puzzle, with possibly hundreds of pieces of evidence that need to fit together properly. Even if one piece is missing or defective, that doesn’t mean you can’t get a good picture of the whole. It depends on the number of pieces that make up the whole and how many and which pieces are missing as to whether you will be able to see the “entire picture”.

[quote]I think part of it is that the research on lie detector tests have been known for some time while we are just finding out the fallibility of eyewitness testimony. We allowed bullet lead analysis into the courtroom at one point, we don’t any more. Science changes things.[/quote]

So are you advocating not being able to use eyewitness testimony at all?

[quote]dmg: Define we? There was no evidence linking Carrillo to the crime scene other than the eyewitness testimony.[/quote]

But it is not necessarily just because of the faulty eyewitness testimony that Carrillo was exonerated. See [url]http://www.ktla.com/news/landing/ktla-francisco-carrillo-free-man,0,813369.story[/url]

[quote]Defense investigator David Lynn testified to a confession he obtained from another man who exonerated Carrillo.[/quote]

[quote]Ineffective defense.[/quote]

The point being that there were many reasons why this case was flawed/overturned: the defendant was 16 years old; conflicting eyewitness testimony; a later confession by someone else; ineffective defense counsel. One could argue but for ineffective defense counsel, the exonerated defendant would probably never have been found guilty, no?

[quote]Hmmm…this may account for why my wife was acting so funny last night. Perhaps she was not my wife! Tonite I will check her ID to be sure; understanding that my eyeball testimony may be unreliable. [/quote]

That’s a sobering thought isn’t. If eyewitness identification really has a 25% failure rate, and there are a class of easy calls, what’s the real failure rate when identifying strangers?

“Comparing driving a car to the courtroom is not a good analogy. “

I’m not comparing a car to the courtroom, I’m defining what a 25% error rate means.

“So are you advocating not being able to use eyewitness testimony at all?”

No. I start with the court admonishment. What I worry about is what a 25% error rate means? Does that include a case in which I see Elaine, someone I know and recognize? If it does, that suggests that the real failure rate is higher?

“One could argue but for ineffective defense counsel, the exonerated defendant would probably never have been found guilty, no?”

That would be more speculative. Clearly without the faulty witness identification, there would have been no case against him to begin with. But I do agree there are multiple factors that have to go wrong for these cases to happen.

Elaine

[quote]So are you advocating not being able to use eyewitness testimony at all?[/quote]

No, but I think it might be reasonable to eliminate using the testimony of someone who has something obvious to gain from testifying.

[quote]erm: “So are you advocating not being able to use eyewitness testimony at all?”

dmg: No. I start with the court admonishment. What I worry about is what a 25% error rate means? Does that include a case in which I see Elaine, someone I know and recognize? If it does, that suggests that the real failure rate is higher?[/quote]

What it means is that eyewitness testimony is not perfect, just as most other evidence is not perfect (not even DNA evidence). As I mentioned before, evidence has to be taken in its totality. And as I said before, a court admonishment is fine…

[quote]That would be more speculative. Clearly without the faulty witness identification, there would have been no case against him to begin with. But I do agree there are multiple factors that have to go wrong for these cases to happen.[/quote]

Hardly speculative in this case. If it could be clearly shown the eyewitnesses could not have seen what they did now, it could have been shown then. Where the heck was the defense attorney? Had he noticed the same thing, this case clearly never would have gotten off the ground…

25% failure rate is well beyond “not perfect” and into the realm of “flawed” particularly in light of easy identifications.

“Where the heck was the defense attorney?”

Overworked and disinterested I believe.

[quote]No, but I think it might be reasonable to eliminate using the testimony of someone who has something obvious to gain from testifying.[/quote]

What did the victim’s son have to gain by identifying the wrong person?

The victim’s son made a mistake and relied on someone else’s account to shape his testimony.

[quote]The victim’s son made a mistake and relied on someone else’s account to shape his testimony.[/quote]

But the victim’s son had nothing “obvious to gain” in this case – I was replying to medwoman’s comment…

And I was asking a general question, not targeting this individual as having something to gain.