In two weeks, at the Vanguard’s Dinner and Awards Ceremony, the work of the Northern California Innocence Project (NCIP) will be honored with a Vanguard Award. On hand to personally receive that award with be NCIP Executive Director Cookie Ridolfi and Legal Director Linda Starr.

In two weeks, at the Vanguard’s Dinner and Awards Ceremony, the work of the Northern California Innocence Project (NCIP) will be honored with a Vanguard Award. On hand to personally receive that award with be NCIP Executive Director Cookie Ridolfi and Legal Director Linda Starr.

The immediate benefit of the work NCIP and other branches of the Innocence Project across the nation is to exonerate those who have been wrongfully imprisoned like Franky Carrillo, who spent 20 years in custody before his 2011 release. Mr. Carrillo will be one of the featured speakers at this year’s event and will present the Vanguard Award to the organization and individuals who helped to exonerate him.

The immediate benefit of the Innocence Project’s work is obvious – freeing those wrongly convicted of crime. The secondary benefit may be just as important from a global level.

Not only has the Innocence Project focused the nation on cases of wrongful conviction, they have inspired efforts like the Wrongful Conviction Registry and other research efforts which have enabled researched to analyze real data on wrongful convictions.

A good example of the fruit of these efforts is a multipart series in the Texas Tribune which analyzed 86 overturned convictions and examined the causes of those. They found that “in nearly one quarter of those cases courts ruled that prosecutors made mistakes that often contributed to the wrong outcome.”

Like the California report on prosecutorial misconduct, co-authored by Maurice Possley, the Vanguard‘s keynote speaker in two weeks and Kathleen Ridolfi, the NCIP exuective director, few prosecutors are disciplined even for misconduct that results in “harm” that results in actual conviction reversal.

In the California Study, they chronicled over 700 cases and found six prosecutors were disciplined. The Texas Tribune only looked at 86 cases, 21 of which involved prosecutorial errors that contributed to the wrong outcome.

The Tribune reports, “The State Bar of Texas, though, said it had publicly disciplined very few prosecutors in recent years. Some lawmakers and criminal justice reform advocates have called for increased accountability for prosecutors whose errors result in wrongful convictions that forever change the lives of innocent people and their families.”

The Vanguard has reported on the case of Michael Morton, who spent 25 years in prison for the killing of his wife in 1986. It was not until 2011 that DNA would exonerate him.

He told the Tribune, “There’s no balancing of the books when you lose two and a half decades of your life to prison.”

“When the murder charge was dismissed in December, it was Texas’ 86th overturned conviction since 1989,” writes the Tribune. “But had the district attorney who prosecuted Morton turned over all the evidence in his files during the trial, the former grocery store manager and his lawyers argue, the entire tragedy could have been thwarted.”

Unlike others, Michael Morton is fighting back, pursuing criminal charges against the former prosecutor who tried his case, now Williamson County state district Judge Ken Anderson.

“I can’t make up for those lost years, but what I can do is prevent what happened to me from happening to someone else,” he says.

The Tribune reports that none of the prosecutors in the cases they tracked received reprimands, in cases where 21 men and women involved in those cases spent a total of more than 270 years in prison before their convictions were overturned.

“In the wake of Morton’s case and other high-profile exonerations, some lawmakers and reform advocates have joined his call for new laws to hold prosecutors accountable for mistakes that derail the lives of the wrongly convicted and their families,” they report.

But they also report, “Many prosecutors, though, argue that reform advocates exaggerate the problem. They say instances of true prosecutorial misconduct are rare and appropriate sanctions are in place to deal with them.”

“You don’t just throw the baby out with the bathwater,” says Tarrant County District Attorney Joe Shannon. “All you’ve got is a few anecdotal situations where things went awry.”

Prosecutors argue that DA’s rely heavily on police investigations, and “if police work is sloppy or incomplete or if witnesses provide conflicting statements, the truth can be obscured even from prosecutors with the best intentions.”

However, a huge problem is one of tunnel vision where “police and prosecutors had made up their minds about a suspect too early in their investigation.”

As Dallas County DA Craig Watkins, who has been fighting for exonerations in cases in Dallas County, notes, “As evidence comes in, we have to follow that path. There’s a failure to follow the other leads.”

The paper quotes Jennifer Laurin, an assistant professor at the University of Texas School of Law who teaches criminal law, and she said, “when the brain is convinced of a particular scenario, people often have trouble processing incompatible information.”

A big problem that the paper found is a violation of the Brady rule requiring prosecutors to provide defendants with exculpatory evidence. They report, “In 17 of the 21 overturned Texas cases with prosecutorial errors, the courts ruled that exculpatory evidence was not given to defense lawyers.”

Part of the problem, Professor Laurin argues, is that if the prosecutor becomes convinced that the individual is guilty, they may fail to recognize evidence that could be exculpatory.

“In the heat of that pursuit, it can become easy sometimes to do the wrong thing for the right ends,” Professor Laurin told the Tribune.

On the other hand, the problem may be simpler, said DA Watkins.

“Truth may not be the issue,” he says. “The issue may be winning.”

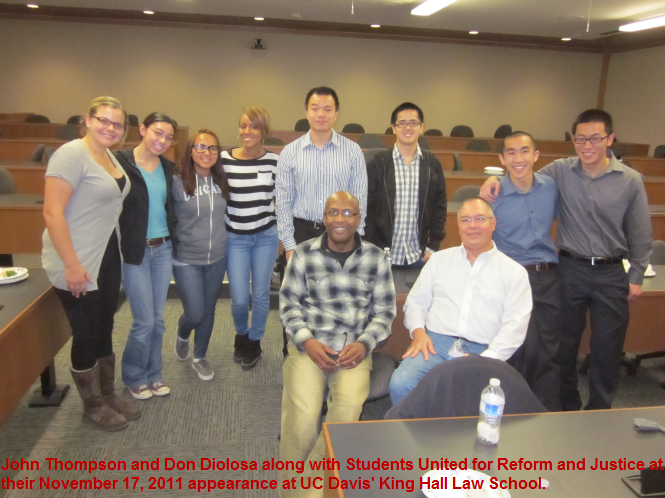

Last November, Students United for Reform and Justice, an organization of students at UC Davis King Hall Law School who have come together to “collectively recognize and respond to the massive injustices that persist in the American criminal justice system,” brought John Thompson and Don Diolosa to speak at the Law School.

The Vanguard will be honoring Students United for Reform and Justice at our Dinner and Awards ceremony.

John Thompson was convicted of murder and spent 14 years on death row before private investigators learned that prosecutors had failed to turn over evidence that would have cleared him at his robbery trial. They also destroyed clothing that would have shown his blood type did not match the blood on the scene.

His convictions overturned, Mr. Thompson was awarded $14 million by a jury for the wrongful imprisonment, but the US Supreme Court overturned it in what some called “one of the most cruel Supreme Court decisions ever,” with Justice Clarence Thomas ruling that the district attorney can’t be responsible for the single act of a lone prosecutor.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was so bothered by the majority decision that she read her dissent from the bench for the first time that term.

We agree that most prosecutors operate in an ethical manner, but they hold positions of ultimate responsibility over the lives of others and that magnifies mistakes and outright misconduct. Those who intentionally commit acts of misconduct need to be held accountable as much as those who commit crimes need to be.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

I suspect what really needs to happen is that some sort of record needs to be kept to see if a pattern of misconduct can be determined for a particular prosecutor. And the misconduct has to be clear. Do we know if anything like this has been attempted?

So the first question is what is the standard: does it have to cause a case to get overturned? Because that’s going to be rare.

I mean in the John Thompson case the prosecutor destroyed evidence, do you really need a pattern there?

But what was the ostensible reason for destroying evidence? Do we know? My thought was that I wonder if prosecutorial misconduct can be tracked to particular prosecutors, or is it really a random phenomenon? It seems to me I vaguely remember a prosecutor in one southern state that had rampant misconduct occur on a pretty frequent basis.

See [url]http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/03/us/orleans-district-attorneys-office-faces-us-supreme-court.html?pagewanted=all[/url]

Elaine,

I know that you have tried to explain this to me before, so bear with me. What would be the objection to all information obtained by the police investigating a crime being turned over to both the prosecution and the defense at the same time. This would seem to me to avoid the problem of the prosecution either intentionally or inadvertently not turning over possibly exculpatory evidence since both sides would be in possession of exactly the same information ?

Based on this article I see very few instances of maliciousness. The article even calls these issues errors.

That’s not surprising. I think in most cases they are errors. That said, if you are making an error because you have tunnel vision and have decided that an individual is guilty, I think that’s hardly reassuring to the person who spends 20 years or more in prison for a crime they have not committed. Moreover, it does not mean that someone in a position of this sort should not be held accountable for their errors.

And to add one more point to David’s comment. Whether deliberate or not, an innocent person is imprisoned, and the real perpetrator is free to repeat the crime. In either event, the potential for the devastation of more than one innocent life.

[quote]I know that you have tried to explain this to me before, so bear with me. What would be the objection to all information obtained by the police investigating a crime being turned over to both the prosecution and the defense at the same time. This would seem to me to avoid the problem of the prosecution either intentionally or inadvertently not turning over possibly exculpatory evidence since both sides would be in possession of exactly the same information ?[/quote]

From [url]http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/prosecutor[/url]

“The prosecutor also must notify the defendant of the evidence against him and must turn over any exculpatory evidence (evidence that would tend to clear the defendant) that the prosecutor possesses.”

So generally the prosecution has to turn over all evidence against the defendant it plans to use at trial. And it must turn over any exculpatory evidence – and what is “exculpatory” is sometimes open to “interpretation”. But to turn over “everything” as you suggest, including work product, is problematic. It has to do with trial tactics. For instance some evidence is not admissible/relevant at trial, but depending on who says what at the trial, can be admissible later as rebuttal testimony to show the witness was not credible.

[quote]That’s not surprising. I think in most cases they are errors. That said, if you are making an error because you have tunnel vision and have decided that an individual is guilty, I think that’s hardly reassuring to the person who spends 20 years or more in prison for a crime they have not committed. Moreover, it does not mean that someone in a position of this sort should not be held accountable for their errors.[/quote]

So are you advocating that prosectors be held accountable in some way for all errors, even if inadvertant/harmless/unintentional? And how do you want them held accountable? And if prosecutors are held accountable for every mistake, whether inadvertant/harmless/unintentional, won’t that impinge on their ability to do their job? Or is there some sort of middle ground for prosecutorial conduct accountability? For example if the misconduct was knowing, willful, repeated, and not harmless?

“So generally the prosecution has to turn over all evidence against the defendant it plans to use at trial. And it must turn over any exculpatory evidence – and what is “exculpatory” is sometimes open to “interpretation”. But to turn over “everything” as you suggest, including work product, is problematic. It has to do with trial tactics. For instance some evidence is not admissible/relevant at trial, but depending on who says what at the trial, can be admissible later as rebuttal testimony to show the witness was not credible.”

If it has to do with “trial tactics” it would seem to me that it would be only the “tactics” that could be affected by the prosecution having information that the defense does not have would be the defense. This is just another way of saying that the playing field is not even, but weighted heavily in favor of the prosecution. If the prosecution gets to decide what is “exculpatory” and since the prosecution is benefitted by “wins” aka convictions,

How can anyone believe that this isnot a set up for both intentional and unintential mistakes in provision of information!

“And if prosecutors are held accountable for every mistake, whether inadvertant/harmless/unintentional, won’t that impinge on their ability to do their job?”

You’ve collapsed three extremely different categories together. There are harmless errors but that word is not used in the common usage of the word which would suggest perhaps a synonym to benign. In the legal setting, harmless simply means a subjective judgment that the impact of the error does impact the outcome. But within that category could be quite serious errors such as the withholding of exculpatory evidence or other problems. You are basically advocating that the prosecutor be potentially bailed out of serious errors if there happens to be enough evidence to convict otherwise.

Along the same lines, unintentional simply means that one does not consciously make the error. But that does not preclude them from being sloppy or careless, it does not preclude them from making the error due to tunnel vision, the assumption of guilt, etc. So like harmless, I don’t think unintentional gets people off the hook.

Now if your argument is actually that error needs to be evaluated on a case by case basis for severity I agree. If your argument is that harmless and unintentional error should not be punished, I disagree.

[quote]If it has to do with “trial tactics” it would seem to me that it would be only the “tactics” that could be affected by the prosecution having information that the defense does not have would be the defense. This is just another way of saying that the playing field is not even, but weighted heavily in favor of the prosecution. If the prosecution gets to decide what is “exculpatory” and since the prosecution is benefitted by “wins” aka convictions,

How can anyone believe that this isnot a set up for both intentional and unintential mistakes in provision of information!

[/quote]

Tactics are employed by both sides. An interesting treatment of this subject is given in John Grisham’s Rainmaker. It’s a fun read…

[quote]You are basically advocating that the prosecutor be potentially bailed out of serious errors if there happens to be enough evidence to convict otherwise. [/quote]

I wasn’t advocating anything, just wanted your take on what should be punished…

[quote]Now if your argument is actually that error needs to be evaluated on a case by case basis for severity I agree. If your argument is that harmless and unintentional error should not be punished, I disagree.[/quote]

Sounds like we’re pretty much in synch on this one…