“Prop. 218, which reads like a ratepayer’s bill of rights, lays out in detail what a city can and can’t do with a variety of taxes, assessments and fees, including water rates,” he writes. Mr. Dunning then argues that “a critical element of Prop. 218 (is) known as ‘proportionality.’ “

He quotes from Prop. 218: “The amount of a fee or charge imposed upon any parcel or person as an incident of property ownership shall not exceed the proportional cost of the service attributable to the parcel.”

He writes, “In other words, if the city has 100 water customers and you use 2 percent of the water delivered to those customers, the city can charge you up to two percent of the total cost, but no more.

“Prop. 218 further emphasizes this point by saying ‘Revenues derived from the fee or charge shall not exceed the funds required to provide the property related service.’ “

Here is the critical portion of Prop 218: “Again, the city can’t charge you more for a gallon of water than it actually costs the city to deliver that gallon of water to you specifically.”

Keep that one in mind as we move through Mr. Dunning’s analysis.

He writes, “The easiest way for the city to comply with the requirements of Prop. 218 is to charge each customer a fixed rate per gallon and be done with it. You use a gallon, it costs you a dollar. You use 100 gallons, it costs you $100. This guarantees that all water users will pay their ‘proportional’ cost of the service.”

The problem that you start running into is that there are costs to the system, even if you do not use any water at all. That requires that one has to have a fixed cost (the cost for using no water at all) in addition to a variable cost (the cost per gallon).

The problem with having a fixed cost is that low-end users end up being charged a lot more per gallon than high-end users.

So when Mr. Dunning writes, “For unexplained reasons, however, the city has come up with a three-headed monster known as the Consumption Based Fixed Rate (CBFR) that calculates the majority of your next year’s bill based strictly on the water you used the previous summer.”

He is actually quite wrong. The reasons for that system have been explained: it is a way of making sure that the low-end users are charged more proportionally to their use than they would under a more traditional rate system, that simply has a fixed rate and variable rate. The CBFR portion bases a part of your fixed portion on past use.

Writes Mr. Dunning, “The city has yet to explain how this ‘look-back’ feature of the CBFR even remotely complies with the ‘proportionality’ requirement of Prop. 218.”

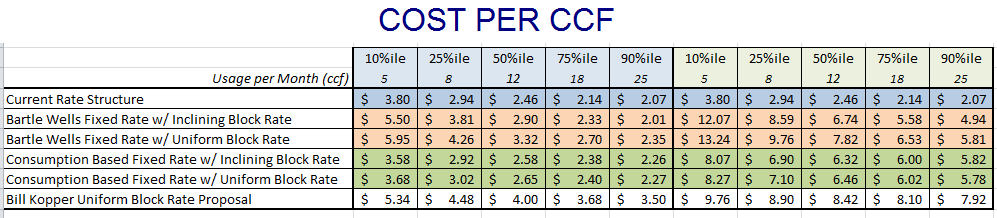

All one has to do is compare the cost per gallon in the CBFR system to a more traditional system to see that CBFR is, in fact, much more fair to the average ratepayer than a more traditional system. In our analysis from December it was not even close.

Mr. Dunning then runs through an exercise here, where he creates “five hypothetical Davis citizens who all use 180 ccf per year and compare their rates.” He argues, “If the city’s rate plan is truly ‘proportional,’ all five ratepayers should have the exact same annual bill because all five are each using 180 ccf of water per year.”

The first names of the citizens just happen to coincide with the first names of the members of the Davis City Council. It is an amazing coincidence.

In his concocted scenario, he shows that the five individuals pay wildly differing amounts for what he argues is the same water usage.

He argues, “Keep in mind that each of our five ratepayers used the exact same ‘proportion’ of water (180 ccf) during the course of a year. The only difference is that their use pattern varied, which is what one would expect in a diverse and interesting community.”

He continues, “The fact their bills vary so wildly for the same amount of water is proof positive Prop. 218’s requirement of ‘proportionality’ is violated by the CBFR rate structure. Dramatically so, in fact.”

He argues, “And for those naysayers who are so in love with the project that they can’t tell fact from fiction, be assured that these figures were double-checked – to the penny – with the city of Davis official in charge of calculating such rates.”

He concludes, “If this thing ends up in court, as it no doubt will, the city won’t have enough attorneys to explain how it costs $1,373.64 to deliver 180 ccf to Rochelle but only $596.04 to deliver the exact same amount of water to Joe.”

Except that Mr. Dunning makes some assumptions that likely lead him to the wrong conclusion.

First, he assumes that the proportionality requirement requires that the rate structure produces roughly the same cost for delivering the same amount of water.

The problem is that that is not what Mr. Dunning’s proportionality requirement says, not at all.

Remember this quote: “The amount of a fee or charge imposed upon any parcel or person as an incident of property ownership shall not exceed the proportional cost of the service attributable to the parcel.”

The critical point is again this: “[T]he city can’t charge you more for a gallon of water than it actually costs the city to deliver that gallon of water to you specifically.”

Nowhere in anything that Mr. Dunning quotes does it say the city has to charge the same amount per gallon for all uses.

His assumption here is that every gallon of water costs the same amount to deliver no matter the time of day or the time of the year.

When you used to make a phone call in the days when only the phone company provided the service, there were different rates for different times of day. The reason you paid less during off-peak hours than during peak hours is that calls during peak hours put more strain on the system and required a larger amount of infrastructure to prevent getting the message that ‘all circuits are busy,’ the phone company’s equivalent to the brownout.

Matt Williams explained this concept rather well nearly two months ago.

“Why choose the summer period for this adjustment?” he asks rhetorically. “If you have ever experienced an electrical brownout (or god forbid an electrical blackout), you know that there are times for public utilities where demand can exceed the system’s capacity to reliably deliver electricity or water. In designing the Davis water system the engineers have worked hard to create enough capacity to avoid a ‘drip out.’ “

He writes, “How do they do that? They simply look at the aggregate consumption history of all the 16,000 customers and see what the maximum usage is, and then design the plant to meet that aggregate usage plus some room for growth. They also add some capacity (almost double) to deal with the ‘peaking’ that happens between 4:00 AM and 6:00 AM when the vast majority of the city’s irrigation systems turn on to keep Davis green.”

Those people who are using more water during the summer are forcing the city to increase the amount of infrastructure they have to deliver water during those 4 am to 6 am hours during the summer when the usage in the system is maxed out.

The long and the short of it is that it costs the system more to use water during those times and during those months than it does in other times and portions of the season.

CBFR approximates this toll on the system, by setting a portion of the costs to the summer usage.

So there are two ways to pass on the costs. One way is that everyone simply pays the same amount of the additional infrastructure. In that system, you end up with the small household that does not use much water outside subsidizing those who use huge amounts to irrigate outside.

As Mr. Williams notes, “One other aspect of the summer peak that is worth noting is that in Davis the amount of water used for irrigation is close to three times as much as is used inside a household or business.”

So the real question is, what is proportionality? Mr. Dunning seems to equate proportionality with an equitable distribution of costs. Therefore each gallon, to be proportional, must cost roughly the same.

But that’s not what Prop. 218 says. Prop. 218 says the cost must be proportional to the cost to deliver the service. Simply put, the person watering their lawn in the summer is taxing the city’s infrastructure more, causing the city to add for peak usage, and therefore ought to be charged a higher rate.

Frankly, the city needs to move to a CBFR system regardless of whether the surface water project passes, because it is a far more equitable system – charging people much more closely based on how much they tax the system.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

It’s hard to justify the total annual cost disparity

that’s because you are looking at proportionality as a cost/ output rather than a cost/input. look at the phone example. you could have the same usage night versus day and yet come to very different costs because the cost on the system during peak hours is far more than the cost on the system outside of peak hours.

the current system approximates the cost based on the meter size, but that does not measure actual strain on the system, a cbfr comes much close to that approximation and sets the fixed costs accordingly.

how do you justify the large costs for those who use almost no water in the bartle-wells system?

So people who water lawns during non-peak hours will have to pay as much as if it were peak hours?

Other water districts charge a fixed cost by the size of the meter, and

variable charge by amount of water used. Nothing complicated or controversial about it.

Phone and power variable billing rates are at least partially due to the fact that they must activate reserve capacity during peak demand, and that reserve capacity production has additional variable costs.

I don’t believe we have the same issue with surface water production, but I could be wrong.

Dunning will kill Measure I “yes” votes. He already has. The reason he can kill yes votes is that environmentalism and resource-usage-class-based egalitarianism is getting in the way of having a rational rate structure.

If the measure fails we can only blame ourselves for failing to keep it simple.

Bob Dunning said . . .

[i]”And for those naysayers who are so in love with the project that they can’t tell fact from fiction, be assured that these figures were double-checked — to the penny — with the city of Davis official in charge of calculating such rates.”[/i]

Mike, there is absolutely nothing wrong with Bob’s calculations. Where he goes astray is in his assumptions. By arguing so long and hard for his “per gallon” model Bob is assuming a system that has very high variable costs and very low fixed costs. Typically in those hinds of situations the product is bought by the business in quantity by the business from a wholesale supplier and then sold to the public at retail. Bob’s examples of a gallon of gasoline fits this model to a tee in another important way . . . the customer is just a customer, and has no ownership stake in the business. Bob has also used other examples like PG&E and groceries and school supplies and vacations. PG&E’s cost structure is very heavily weighted toward variable. They buy their electricity by the kilowatt hour on the open market. They buy their natural gas from natural gas pipeline companies. Grocery stores are also heavily weighted toward variable costs because virtually every product they sell is purchased and then marked up. Same thing for school supplies from Office Depot.

Bob (and all of us in Davis) is both a customer of the water system and also an owners of it. It is kind of like a vacation time share cabin up at Tahoe or Oregon or Palm Springs. Because each of us are owners of the vacation home, whether you go to the vacation home or not, there are a substantial amount of fixed costs that are due and payable regardless of whether you incur the variable costs of driving to Tahoe/Oregon/Palm Springs to use the vacation house or not. So each of us pay a share of those fixed costs (the Distribution Charge in CBFR).

If you have ever been involved in a vacation time share you know that one of the challenges is deciding how to divvy up the available weeks and/or weekends. One of the tried and true methods for solving that is a “subscription” system where people reserve particular weeks and/or weekends and pay a subscription fee for the amount that they reserve. There is only so much “supply infrastructure” available in a time share and if place more load on the timeshare (reserve more weeks/weekends) you pay more and you pay that subscription amount whether you actually use the timeshare or do not use it.

Season tickets to a sports team work the same way. You have the variable costs associated with driving to the arena, parking, buying your kid a hot dog and/or souvenirs, etc., but whether you actually go to the game or not, you are on the hook for the cost of the ticket.

The CBFR Supply Charge works very much like those season tickets. Up front you have the ability to choose how many games you want to include in your season ticket package. The winter months are like the preseason exhibition games/scrimmages. They come free as part of the season ticket package. In Bob’s scenario Joe decided to go to 25 preseason games, but only 5 regular season games, so his “load” on the season ticket package is 5. Dan’s load is 20. Brett’s is 15. Lucas’ is 10. Rochelle’s is 25. They all send in their respective checks for their season ticket packages (the Supply Charge in CBFR), and then when and if they actually go to one of the games they have subscribed for, they incur the variable expenses of using their tickets (the Use Charge in CBFR).

If Rochelle finds that she subscribed for 25 tickets in 2011 but only actually went to 15 games, when the time comes to decide on how big her 2012 season ticket package should be, she looks at her 2011 usage and matches her subscription to her historical use.

Similarly, if Joe finds that south of France isn’t as rewarding as Davis, and actually goes to 20 games (5 with his season tickets and 10 by buying them at the box office), when the time comes to decide on how big his 2012 season ticket package should be, he looks at his 2011 usage and matches his 2012 subscription to his historical use.

That is how the CBFR “Supply” Charge works. If you p you . Subscribe for more

If you do use your vacation home in the summer you clearly pay more in the summer than in the winter, but the monthly mortgage payment and insurance payments and property taxes are uniform in all 12 months. Said another way, you are still paying for your summer usage in the winter.

eagle eye said . . .

[i]”Other water districts charge a fixed cost by the size of the meter, and a variable charge by amount of water used. Nothing complicated or controversial about it.”[/i]

eagle eye, it isn’t controversial because no one has been paying attention all these years, even though the controversy is as plain as the nose on our face.

Proposition 218 proportionality means that all rate payers should shoulder their fair share of the not only the variable costs but also the fixed costs of the water system that reliably delivers our water to us. In the current rate system in place in Davis, a ratepayer with a 3/4 -inch meter (there are over 12,000 of them), who used 51 hundred cubic foot units (ccf) per year in 2011 paid $2.71 per ccf, while the actual ratepayer who used 600 times that amount (3,040 ccf) paid only 5 cents per ccf. Yes, you read that correctly … literally thousands of Davis ratepayers paid 600 times more per unit than other Davis ratepayers did. The obvious legal question that reality poses is, “Why should the people who use very little water pay 600 times more than the people who use a whole lot of water?” That question is particularly meaningful when put into the context of:

1)Article X of the California Constitution and Senate Bill N. 7 (Statewide Water Conservation), which together require water suppliers to measure water deliveries and adopt a pricing structure for water customers based at least in part on quantity delivered, and where technically and economically feasible implement additional measures to improve efficiency.

2)The fact that the engineers hired by the City of Davis and the Woodland/Davis Clean Water Agency had to design in 600 times more capital expenditures on the Davis Woodland Surface Water Plant to support the high user than they had to design in to support the very low user.

3)The capital costs of the Davis Woodland Surface Water Plant are being allocated to the two respective jurisdictions, the City of Davis and the City of Woodland based on the proportional aggregate load each jurisdiction will place on the surface water plant

The proxy for proportionality in the Davis rate structure is the fact that four groups of Davis citizens are making recurring annual charitable donations to the large water users in Davis. Those four groups are 1) senior citizens, 2) low-income residents, 3) residents who have unfortunately lost their jobs in this down economy and 4) residents who have worked hard to conserve water.

If that isn’t controversial, I don’t know what is.

Matt: How did your email discussion back and forth with Bob Dunning go. Your post above seems to agree with his point.

SODA, Bob’s calculations of the five example rates is mathematically correct. However, Bob’s argument is a bit like getting in a car to go from Davis to San Francisco and hopping on the eastbound ramp of I-80. No matter how well you manage the mathematics of the mileage you drive, you will not accomplish the goal of arriving at the Ferry Building.

In our e-mail interchange Bob’s way of dealing with the fact that he is not just a customer but also an owner was to say, [i]”I don’t own anything in Oregon.”[/i] and then disappear from any further conversation about the issue. The fixed costs for the supply infrastructure are a reality that he does not want to acknowledge. It is as if the fixed capital construction costs for the six deep aquifer wells and the two above ground storage tanks have magically evaporated.

The ‘hypocrites’ are in rare form… Dunning says fees/rates should be equal for each gallon consumed. OK… then we should have a flat income tax where each wage earner pays the same percentage for what they earn, whether it is $20k or $2,000 k. Every property owner, no matter how long they have lived in the house they owned, should pay the same in property tax (perhaps adjusted to reflect how many people reside there, to reflect the likely demand they would have on public services). We should eliminate SS taxes as many will have to pay into the system with no expectation of receiving one dime of it. On the tax/fee side, I’d argue that the richer folks should pay less, as they will less likely need government services. “Proportionality”… fully embrace it, with all its consequences, or clam up.

I agree with Matt’s comments on the so-called “traditional” rate structure as adopted by the CC in August 2010 without a rate study, and the proposed Bartel Wells Associates 2-year “transition” to the CBFR that bears Matt’s DNA strands. I read the case law given to the WAC by our so called expert water attorneys, and none of those cases are fully applicable to the situation. (These are the same attorneys who certified the bogus Sept 6, 2011 rates, opined that our 2011 water rate referendum was illegal, and now certified the current rate systme as meeting Prop 218.)

(PS, these same attorneys hid the Aug 24, 2011 Court of Appeals decision of City of Palmdale, then told the CC when I protested that the decision did not apply to our rate system. Later they back-walked it, and admitted it does control the analysis.)

I have been staying out of the CBFR, because I flat did not understand it, but I have never liked the idea of a “look-back” process for setting current rates, and now Dunning has 5 hypothetical rate payers who clearly pay vastly different rates for the same annual consumption of potable water. City water staff have apparently confirmed his numbers, so what’s left is the idea that you can charge someone high rates for peak use in, say, May and October, and a lot less for, say, the months of April and November.

If memory serves me, when Matt first introduced the Williams Loge Rate Proposal to teh WAC, it looked a lot different than now.

Matt, may I ask that you put together (in your copious quantities of spare time sitting down there watching your cacti grow in El Macero) on your ever-present laptop (your public wants to know if the shower water damages it) a historical summary of the major changes to CBFR since it was first introduced to the WAC?

One change I remember is your Version 1.0 had to do with the rate calculation was based on your proportional use of the total city use (a percentage), but after going through the political sausage factory, that calculation is now a fixed montetary rate?

Also, what influence did the bond-broker spanking machine have on your pride and joy Ver. 1.0 W-L system?

I remember at one CC meeting, the utility manager from Sacramento looked like he was feeling something happy and medicinal (now legal in Colorado) when staff talked about how the amended Ver. 2.0 would work for stability of the income stream. What was that all about?

[i]The ‘hypocrites’ are in rare form… Dunning says fees/rates should be equal for each gallon consumed. OK… then we should have a flat income tax where each wage earner pays the same percentage for what they earn, whether it is $20k or $2,000 k[/i]

I am in support of that tax system.

I also pay the same per gallon for gas as the does the poorer and wealthier person… no matter how much each of us consume.

“I also pay the same per gallon for gas as the does the poorer and wealthier person… no matter how much each of us consume. “

You seem to be conflating the issue of affordability with that of proportional costs.

I see a much more complex impact of gas consumption:

1. You assume some of your own fixed costs for your variable use of your vehicle by paying a hidden but additional cost per mile.

2. On the other hand, we don’t have an effective way of charging, in most cases, for the cost of the wear and tear on the vehicle. Some of that is subsumed into the gas tax that pays for some road repairs. On the other hand, there really isn’t the same type of peak use tax.

3. We have not figured out how to factor in the costs of environmental degredation into vehicle use.

Thus, I would argue, the people at the lower ends of use end up with proportionally picking up a higher share of the fixed costs.

Your error is in apparently assuming that the status quo is ideal when it appears at best suboptimal.

Michael Harrington said . . .

[i]”If memory serves me, when Matt first introduced the Williams Loge Rate Proposal to teh WAC, it looked a lot different than now.

Matt, may I ask that you put together (in your copious quantities of spare time sitting down there watching your cacti grow in El Macero) on your ever-present laptop (your public wants to know if the shower water damages it) a historical summary of the major changes to CBFR since it was first introduced to the WAC?

One change I remember is your Version 1.0 had to do with the rate calculation was based on your proportional use of the total city use (a percentage), but after going through the political sausage factory, that calculation is now a fixed montetary rate?”-/i]

Actually Michael the change you refer to is cosmetic. The calculation still is based on proportional use of the total city use. The units are slightly different, but the principle is the same.

The one more substantive change is that the CBFR at one point covered all the fixed costs, but Bartle Wells and Kelly Salt prevalied on us to recognize that certain fixed costs are not related to actual water consumption (billing, accounting, fireline water pressure, etc.) and that those fixed costs should be handled by a separate charge . . . the Distribution Charge. Between the Distribution Charge and the Supply Charge, 100% of the system’s fixed costs are covered . . . no more, no less.

Michael Harrington said . . .

[i]”Also, what influence did the bond-broker spanking machine have on your pride and joy Ver. 1.0 W-L system?

I remember at one CC meeting, the utility manager from Sacramento looked like he was feeling something happy and medicinal (now legal in Colorado) when staff talked about how the amended Ver. 2.0 would work for stability of the income stream. What was that all about?”[/i]

His testimony before Council can be seen at the 3:19 point in the video of the 12/11 Council meeting. It speaks for itself. Bottom-line the risk reduction features of CBFR will mean lower interest rates for Davis when it goes to the bond market.

[i]You seem to be conflating the issue of affordability with that of proportional costs.[/i]

I don’t think so. You nor anyone else has made a strong enough argument for progressive or seasonally variable rates based on proportionate cost of production. You variable rate schemes are simply driven by environmental and/or class-based resource consumption management impulses.

[i]2. On the other hand, we don’t have an effective way of charging, in most cases, for the cost of the wear and tear on the vehicle. Some of that is subsumed into the gas tax that pays for some road repairs. On the other hand, there really isn’t the same type of peak use tax. [/i]

There is wear and tear on appliances and plumbing and fixtures based on water use.

I think you are tripping up on this comparison. It is a valid one. The cost of infrastructure for both water and gas are fixed. There are variable costs that are completely handled only by charging a fixed variable cost.

Where we get into trouble is thinking about conservation when devising rates. We want to encourage conservation and so we inject that into the rate structure. However, that makes it unfair in a number of circumstances as Dunning pointed out. I think there are plenty of incentives to reduce consumption without creating a complex rate structure that turns people off from the project.

A number of environmentalists have proposed a similar scheme for driving… somehow keeping track of miles driven and charging a higher registration tax based on mileage. If the state owned the gasoline business, there is no doubt that the “smart” and progressive people in positions of power and influence would be trying to implement variable gas prices so that the poor and less-frequently driving class of people got a price reduction, and those economically successful people that had to drive more miles would get hit with over-market gas charges.

Here is what I have to say about all of that thinking. JUST STOP IT. Keep it simple. Don’t try to solve all the world’s problems with commodity pricing.

Those that want this surface water project should start demanding a straight variable rate structure. Otherwise Measure I will fail, and I personally will blame you for my broken applicances and plumbing, and the need to use 100 lbs of salt every year going into the Delta.

If Howard Jarvis Taxpayers gets interested in these messed up rates, this pig dressed up as a water project is done for now.