When a person is wrongly convicted for a crime, there is the presumption that the process broke down. Often we look to prosecutorial misconduct, mistakes by investigators and ineffectual defense. As this year was the 50th anniversary of the seminal Supreme Court decision, Gideon v. Wainwright, there has been much attention focused on the decline of indigent defense.

We have found that public defense is strained by declining budgets, high workloads and other problems.

As San Francisco Public Defender Jeff Adachi said in his speech at the UC Hastings College of Law, “This crisis in indigent defense is one of the greatest ethical dilemmas in our legal system. If there is to be liberty for all, then a basic contradiction exists if a poor person’s justice means being represented by a public defender who is handling 500 felony cases.”

“A few years back, I sat on the American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on Indigent Defense and I was able to see the quality of representation throughout the United States,” he said. “I can tell you that even today, the poor quality of representation provided to people in the criminal courts remains a major problem. In many states, public defenders do not have the power to refuse cases when their caseloads exceed what any lawyer could possibly handle. Yet the system, including judges, prosecutors and defenders, often turns a blind eye to what amounts to everyday injustice.”

However, if Matthew Mangino, a counsel with Luxenberg, Garbett, Kelly and George and the former district attorney for Lawrence County, PA, is correct, the problem goes beyond that of a failed system of public defense.

“More than 75,000 prosecutions every year are based entirely on eyewitness identification. Some of those identifications are erroneous,” he writes in a recent column. “The U.S. Supreme Court believes that cross-examination is the panacea to eyewitness misidentification.”

He adds, “The U.S. Supreme Court, as recently as last year, reaffirmed that the rules of evidence, jury instructions and most importantly, cross-examination are safeguards that protect an accused from the use of unreliable evidence like inaccurate eyewitness identification.”

But he also notes that Jules Epstein, in his article “The Great Engine that Couldn’t: Science, Mistaken Identification, and the Limits of Cross-Examination,” argues “that even effective cross-examination can be inadequate to protect an accused wrongfully convicted through the testimony of an eyewitness.”

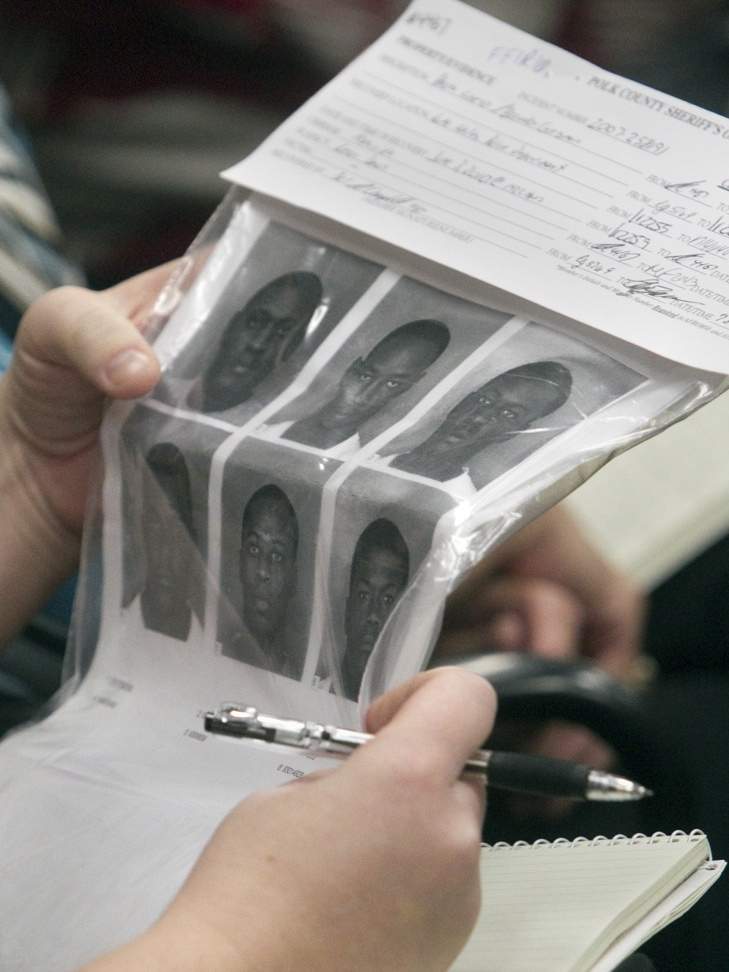

Here Mr. Mangino relates the 1984 trial of Ronald Cotton, where a college student would be assaulted by an unknown intruder into her apartment. She was able to pull the defendant’s picture out of a photo lineup.

She said Mr. Cotton’s photograph “looks most like her assailant.” The victim would “hesitatingly” pick Mr. Cotton out of a lineup and ultimately testified that he was her attacker at trial.

During cross-examination in this case, the victim acknowledged that she did not have her eyeglasses on during the assault and she also acknowledged that there were poor lighting conditions in the room, as “the light source for the identification came from blinds, a bedroom window and lights from a stereo.”

While all of these facts were established during trial through cross-examination, Mr. Cotton was nonetheless convicted of the crime only to be exonerated through DNA evidence.

Jules Epstein, Mr. Mangino writes, argues that “judges and lawyers must disabuse themselves of the notion that cross-examination’s great engine has the efficacy to redress and prevent the recurrence of mistaken identification.”

“Advances in the social sciences and technology have cast a new light on eyewitness identification. Hundreds of studies on eyewitness identification have been published in professional and academic journals,” Mr. Mangino continues. He cites the study by University of Virginia Law School professor Brandon L. Garrett which found that eyewitness misidentifications contributed to wrongful convictions in 76 percent of the cases overturned by DNA evidence.

At least one U.S. Supreme Court Justice, Sonia Sotomayor, has acknowledged the shortcomings of cross-examination.

She wrote, “Eyewitness identifications’ unique confluence of features – their unreliability, susceptibility to suggestion, powerful impact on the jury, and resistance to the ordinary tests of the adversarial process – can undermine the fairness of a trial.”

Matthew Mangino offers no solutions to the problem of eyewitness. His anecdotal evidence, however, suggests that the problem does not rest with and is not solved by a vigorous cross-examination.

The Innocence Project has been concerned with this issue for some time, as it is one of the leading causes of wrongful conviction.

They recommend five steps:

- Blind administration: Research and experience have shown that the risk of misidentification is sharply reduced if the police officer administering a photo or live lineup is not aware of who the suspect is.

- Lineup composition: “Fillers” (the non-suspects included in a lineup) should resemble the eyewitness’ description of the perpetrator. The suspect should not stand out (for example, he should not be the only member of his race in the lineup, or the only one with facial hair). Eyewitnesses should not view multiple lineups with the same suspect.

- Instructions: The person viewing a lineup should be told that the perpetrator may not be in the lineup and that the investigation will continue regardless of the lineup result. They should also be told not to look to the administrator for guidance.

- Confidence statements: Immediately following the lineup procedure, the eyewitness should provide a statement, in his own words, articulating his the level of confidence in the identification.

- Recording: Identification procedures should be videotaped whenever possible – this protects innocent suspects from any misconduct by the lineup administrator, and it helps the prosecution by showing a jury that the procedure was legitimate.

The New Jersey Supreme Court in 2011 made a ruling that was aimed at resolving what they called the “troubling lack of reliability in eyewitness identifications.”

Last year, for the first time, the New Jersey courts are having judges instruct jurors in order to improve their evaluation of eyewitness identification.

The New York Times reported last year, “A judge now must tell jurors before deliberations begin that, for example, stress levels, distance or poor lighting can undercut an eyewitness’s ability to make an accurate identification.”

“Factors like the time that has elapsed between the commission of a crime and a witness’s identification of a suspect or the behavior of a police officer during a lineup can also influence a witness, the new instructions warn,” they add.

“You should consider whether the fact that the witness and the defendant are not of the same race may have influenced the accuracy of the witness’s identification,” the instructions say.

“Human memory is not foolproof,” the instructions say. “Research has revealed that human memory is not like a video recording that a witness need only replay to remember what happened. Memory is far more complex.”

In addition, in California, Assemblymember Tom Ammiano’s AB 604 would promote the use of research-proven witness identification procedures to reduce the incidence of wrongful convictions.

“Prosecutors and police investigators are often under pressure to identify a culprit. It’s important to make sure they identify the right person,” Assemblymember Ammiano said in a press release.

“There is research that has shown that police can improve the reliability of their investigation, so the bill rewards the techniques that would help like the double-blind administration,” Assemblymember Tom Ammiano told the Vanguard in a phone interview a few months ago.

When a trial introduces witness identification that took place before the trial, the bill would say that the judge must give the jury an instruction indicating that certain techniques provide better results in reliability and that jurors can take that into account when deciding on the reliability of the ID,” he said.

The bill requires trial judges to give juries instructions about witness identification procedures. The instruction would tell jurors they could take into account the way in which identification took place, and whether it met certain criteria. The presence of that instruction would create an incentive for investigators to use more careful procedures.

Among the procedures that improve the quality of identification are sequential presentation of photo lineups (as opposed to showing all photos at one time) and having double-blind administration, in which a party not directly involved in the case administers the lineup presentation.

According to the bill, “In any criminal trial or proceeding in which a witness testifies to an identification made before trial, either by viewing photographs or in person lineups,” the court would issue an instruction to the jury.

The instruction would read: “The procedures listed in Section 683.3 of the Penal Code increase the reliability of eyewitness identifications. As jurors, you may consider evidence that police officers did or did not follow those procedures when you decide whether a witness in this case was correct or mistaken in identifying the defendant as the perpetrator of the crime.”

The jury would be further instructed, “If police officers did not follow the procedures recommended in Section 683.3 of the Penal Code, you may view the eyewitness identification with caution and close scrutiny. This does not mean that you may arbitrarily disregard his or her testimony, but you should give it the weight you think it deserves in the light of all the evidence in the case.”

—David M. Greenwald reporting