The debasement of faculty labor over the past decade is really a battle over what happens inside the classroom.

By Claire Goldstene

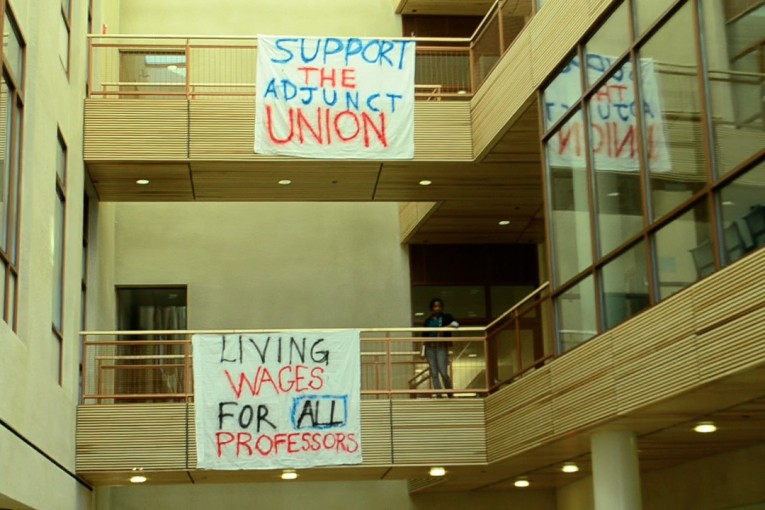

Adjunct unionization is on the rise on college campuses across the United States.

The ivy-covered walls of academe are hiding a growing class of low-wage workers. Some earn so little that they qualify for food stamps. Most lack access to employee-sponsored health and retirement benefits, are unable to pay down their student loan debt, and are deprived of opportunities for career advancement.

Who is this growing class of low-wage workers? Temporary and part-time professors.

Professors in this category shuttle among three or more campuses and teach upward of eight classes a semester to hundreds of students in order to cobble together a less-than-modest living. And most do not know from one year to the next, or even from one semester to the next, if they have a job.

Temporary faculty now comprise over 75 percent of college teachers nationally, which includes one- or multi-year contract faculty, temporary full-time faculty, and adjuncts, paid on a per-course basis. According to the Adjunct Project, the median pay for a three-credit course is $2,987.

Education is an inherently political endeavor. The debasement of faculty labor over the last number of decades—especially the last ten years—is really a battle over what happens inside the classroom. A system of higher education where the bulk of teachers lack job security, are grossly underpaid, and often find out just days before the semester begins that they are scheduled to teach necessarily degrades the quality of education.

A financially-stressed and time-constrained professoriate, in ways both conscious and unconscious, teaches in an inhibited manner. Anxious about contract renewal, fearful of negative student evaluations, and lacking the time and energy to fully dedicate themselves to any particular class, these faculty are unlikely to engage students in controversial discussions that question the status quo.

In this environment, teaching that emphasizes critical thinking, engages complex ideas, and presents students with perspectives that might upset existing social arrangements gives way to teaching more focused on rote memorization. Ultimately, all of this reinforces social and economic inequality—the very thing education is supposed to combat.

Despite claims to the contrary, the low pay and uncertain employment status of contingent faculty are not the inevitable result of supply and demand, where an overabundance of PhDs has depressed wages. Indeed, more students than ever attend institutions of higher learning, and the demand for qualified teachers is at an all-time high.

What has diminished is the supply of tenure-track jobs. This reflects, in part, declines in federal and state resources for higher education, but also decisions to direct money toward the construction of new facilities, including such things as rock-climbing walls and luxury dorms, and the ballooning number of highly paid administrators and their large support staffs, who greatly outnumber faculty in most cases.

The tendency to apply a corporate model of governance and management to universities is connected to an impulse to temper the historic role of colleges as sites of political activity and protest. Much of the anti-war and social activism of the 1960s emanated from universities among college students. But a financially insecure teaching core is less likely to encourage disruptive thinking and action on the part of students. Thus, amid these structural shifts in higher education, most students’ college experience is less about critical engagement with complex ideas and more about technical training.

This is particularly the case in community colleges, where the preponderance of adjunct faculty is the greatest, and where the student population is comprised mostly of ethnic and racial minorities, those from working-class families, and first-generation college students. Increasingly, community colleges focus less on transfer to a four-year university and more and more on providing discrete job training. Doing so sustains class hierarchies, as students at “elite” universities continue to enjoy an educational experience centered on the intellectual breadth of the liberal arts, critical thinking, and a holistic understanding of education with the expectation that they will occupy more influential and higher-paying jobs.

As more students than ever attend institutions of higher learning, the working conditions of temporary faculty have national political ramifications. Like other low-wage workers, contingent faculty are successfully organizing. Through various forms of collective action, they are demanding better working conditions and higher pay.

Much is at stake in this battle. The issue is not only whether college faculty will receive a living wage but also whether they will enjoy the financial and professional security essential to controlling what higher learning is—and should be—all about.

Claire Goldstene has taught United States history at the University of Maryland, the University of North Florida, and American University. She is the author of The Struggle for America’s Promise: Equal Opportunity at the Dawn of Corporate Capital (2014). Dr. Goldstene can be reached at claire.goldstene@yahoo.com.

Adjunct Project, the median pay for a three-credit course is $2,987.

Does anyone know what they are plaid in CA JCs or at UCD?

A friend’s wife makes close to $100K “teaching” Internet courses at a CA JC and the many articles on the CCSF mess said high pay for low work was the reason for the cash flow problems.

At UCD, about $7,000 per course/quarter, if you’re contingent faculty. At least in the department I teach in, unless there are unusual circumstances, you will not get more than about 2 courses per year. And once you hit 17 quarters of teaching, they may not re-hire you, because then you would qualify for review for Lecturer with Security of Employment.

A full-time Lecturer (without “security of employment,” so re-hiring decisions are made year-by-year) makes about $51,000 per year, and the teaching load is 7 classes per year, usually 3/2/2.

SoD: Does anyone know what they are plaid in CA JCs

It probably varies by district, but in the local Los Rios Community College District, this is the salary schedule for adjuncts on a semester basis.

Per hour, looks pretty well compensated to me. Could see where too few hours could be a problem, but that’s not an issue of pay…. an issue of workload.

Just knock off thrity percent or more for SSI (15%) and Medical benefits (depending on family), because where I work, they pay none of that until you are “career”.

Are you self-employed?

IF I mention the benefits they do not pay, it adds up.

$1800 a month which everyone on this forum seems to think is a living wage, let’s break it down: Kaiser just sent me a kind threat that I “need” to sign up for something before the deadline at $600 a month. 15% of $1800 is $270. Parking is $50 a month or $9 a day. $920.

If I work the Bay area I work for twice what UC pays, and I have gotten away from self-employment, because self employment tax is a killer.

More than half of the gross goes to the guvmint or taxes, same thing.

Rent? $800 for me, lots less than other people pay, but I try to fill in with other work. So far gas and food are not even on the table. Literally.

I hope that gives a clue Mr Shor. I am always looking for more work!

If you are self-employed, you pay the full SSI: 12.4% (and 2.9% for Medicare). If you are an employee, regardless of where you work, you pay half of it and your employer pays half of it. Each of you pays 6.2%, (and each of you pays 1.45% for Medicare).

As I understand it, that per hour schedule is calculated only for every hour spent in front of the class. It is meant to include all the time spent grading, lecture/lab prep., office hour(s) & after class student contact.

“The tendency to apply a corporate model of governance and management to universities is connected to an impulse to temper the historic role of colleges as sites of political activity and protest.”

Historic role of colleges is to incite political activity and protest? Gee, and here I thought it was to get an eduction. Silly me!

The role of the universities is to study and examine their field of expertise in a non-biased manner. You are never going to do that when you rely on industry funding. Then the professors are supposed to teach their students the unbiased findings of their research. The Chicago School of Economics was so powerful prior to Greenspan’s pitiful admission that he never saw the crash coming because he believed the market was infallible and would self-correct. I wonder how many economists we have now who were taught anything other than the market rules theory of economics. And what is our guiding principle now? Because the market isn’t infallible.

Well, the author is a ‘history’/liberal arts type, who probably believes that engineers/physicists/chemists, etc. should just go to trade school, and have no business at a University. Comes out several times in the piece.

The university has taken on the corporate model as evidenced by the disparity in remuneration between the top echelon and the people paid to actually teach students. This is the same model used by corporation and uses the same logic to justify obscene executive salaries while paying the people who actually produce something a pittance. We also see the corporate model when we allow our research to be funded by industry. When a company pays for research, the project and its goals will be structured in a biased manner with results likely for benefit industry.

From Food and Water Watch: In 1982, the Bayh-Dole Act began to encourage land grant colleges to partner with the private sector on agricultural research. A key goal was to develop products like seeds which were sold to farmers under an increasingly aggressive patent regime.

About one quarter of funding for ag research now comes from private donations which results in research that benefits big ag and discourages independent research. It diverts public research away from issues like rural economies, environmental health and the public health implication of agriculture.

Industry funded research routinely produces favorable results for industry sponsors and goes on to influence policy makers who use those results to make the rules that govern the industry’s business operations.

Along similar lines, we see justification for executive salaries from economists but Luigi Zingales of the University of Chicago had done some interesting research that show economists exhibit a pro-business pro-market bias. If your an academic economist, you’ll be strongly aided in your research by access to industry information which requires they trust you to cooperate. When you publish favorable work, you gain their trust which leads to more access, more publications, those publications being cited more and eventually more job opportunities. Zingales looked at 150 of the most downloaded papers on executive compensation. He classified them as positive or negative. The results show “Articles in major economic journals have a clear pro-business bias. Managerial reviews tend to publish fewer articles when the conclusion is compensation should be lower. He found articles in favoring high executive compensation receive more citations.. He concludes “these results suggest the optimal strategy for junior faculty who works on executive compensations and wants to maximize her chances to get tenure is to write articles that show the level of compensation is appropriate and the sensitivity to performance should be increased.”

Zingales suggests this may exert a deep influence over the profession, systematically influencing advice economists offer policy makers or EVEN THE IDEAS THEY ALLOW TO ENTER THEIR DISCUSSIONS.

We are currently raising tuition in order to pay higher executive and star professor compensation packages and I highly doubt their is anyone (except Gov. Jerry Brown) who will stand up and argue that we should not let our land grant colleges follow the corporate model.

And let me ad that our push for innovation centers is just an off-shoot of industry funding research then taking those findings and funding start ups to develop and market new products. Turn me into a toad if the funders of the research don’t benefit from these innovation centers.

Davis Burns–excellent comment! I don’t think most people are aware of the systematic bias that has been perpetuated further over the decades in schools of economics and business. There is little critical evaluation of the foundations of the currently marketed economic paradigms. I’m reproducing the salient portion of your post below:

“If your an academic economist, you’ll be strongly aided in your research by access to industry information which requires they trust you to cooperate. When you publish favorable work, you gain their trust which leads to more access, more publications, those publications being cited more and eventually more job opportunities. Zingales looked at 150 of the most downloaded papers on executive compensation. He classified them as positive or negative. The results show “Articles in major economic journals have a clear pro-business bias. Managerial reviews tend to publish fewer articles when the conclusion is compensation should be lower. He found articles in favoring high executive compensation receive more citations.. He concludes “these results suggest the optimal strategy for junior faculty who works on executive compensations and wants to maximize her chances to get tenure is to write articles that show the level of compensation is appropriate and the sensitivity to performance should be increased.”

Zingales suggests this may exert a deep influence over the profession, systematically influencing advice economists offer policy makers or EVEN THE IDEAS THEY ALLOW TO ENTER THEIR DISCUSSIONS.”

Although it is true that universities do tend to have a strong liberal bias in their humanities departments; the business and economics departments are staunch supporters of the status quo and of the current directions in national and international business and economic policies (next up is the TPP, being debated quietly behind closed doors and not open for public debate; and which will further subjugate national sovereignity to corporate boards). Heavens forbid that any aspect of modern capitalism should be subjected to critical review!–a false communist(or socialist)/capitalist dichotomy is set-up, in which the public is led to believe our only choice is between one extreme or the other; or if any attempt is made to moderate some of the more extreme elements of modern capitalism or ‘free’ trade, we are foolishly meddling with the goose that laid the golden egg, or sliding down the slippery slope!–all of the rhetorical edifice, of course, serves the purpose of protecting and perpetuating the wealth and power of the 0.001%, for which the system is working very well, thank you.

If the people who oppose illegal immigration would work to repeal NAFTA and end the war on drugs (in which the US ends up giving drug lords money to stop drug trafficking) then the Mexican economy could recover, farmers might be able to return to farming, communities would no longer be terrorized by rampant murder by warring drug lords and Mexican citizens could and would return to their homes to earn a safe and decent living. It would not end our need for Mexican labor in the fields but it would end people risking their lives to make dangerous journeys north in the hopes of leaving violence behind and finding work. America has created the problems we have with under and unemployment by hollowing out our cities and sending manufacturing to China leaving only low paying service jobs here in our country. Currently, wealth is made by financial exchanges with nothing made and no value added.

You are correct. TPP is being fast track, there will be no debate and it will be passed which will hurt the poor and middle class even more than NAFTA. We are on a course with disaster.

The first priority is to cut the cost of quality education that has skyrocketed well above the rate of inflation. Do that and then let’s talk about paying the UC low-skill workers more.

Are you seriously calling adjunct faculty “low-skilled workers?” If so, that is completely untrue (at least in the vast majority of cases I’m familiar with, including my own).

They are the fast food workers of the University, not meant to stay. Some managed to be there for decades, while maybe waiting for a chance at tenure, or an opening in their field. Just as TAs are usually there for a few years, some stay longer because of family or other reasons.

Instead of treating people like colleagues and giving them a place in the University, it depends on the department whether they value them enough to treat them fairly.

In the last several years I have had a temporary contract and each year costs to work there go up, and benefits go down. Is it any wonder people complain?

If you mean that it’s no wonder the adjunct faculty themselves complain, no–I don’t wonder at that at all, considering I’m one of them. I was taking exception to what a commenter above was saying about “low-skilled UC workers.” I was arguing that the vast majority of adjunct faculty I know at UCD (and in other institutions) are far from “low-skilled.”

And given that only about 30% of faculty positions are now tenure or tenure-track, I don’t think these workers are “not meant to stay,” since that seems to be the direction that colleges and universities are going in.

Fortunately, I’ve had a good experience with the vast majority of faculty in my department treating me fairly and as a valuable contributor to the university’s teaching mission.

Yes, KSmith, I should have said Adjunct Faculty instead of “People”.

I have worked in places that actually wrote letters to tell me as I left “they should have done more” for me. I am not an Adjunct anything, but I supported them and professors during my time in academic departments. It is worse in Non-academic departments.

The rates they pay are about 30% under community colleges and Cal State from the studies and research I have done. In spite of the research money making up 85% or more of the UC budget, it gets sucked up for “other things”.

I am glad to hear you are valued in your position.

That was an unfortunate mistake on my part. I agree with you that adjunct faculty are not low skilled. I meant to type lower-skilled. And maybe that isn’t correct either… lower credentialed, lower experienced… I think those are possibly more appropriate.

I was thinking about this more like a professional service organization where the adjunct employee is the paraprofessional. My point is that we need to address the overall cost of higher learning before we address any more complaints of low pay for any employee of the university. Because any increase in pay will transfer to the students.

Thanks for clarifying, Frankly.

I think those descriptions (lower credentialed and lower experienced) are not more appropriate either–at least not in all cases. If we’re talking experience -teaching-, oftentimes adjunct faculty have more experience (as far as number of classes taught) than tenured faculty. They also usually have the same credentials (PhDs and publications).

Admittedly, my experience is only with particular departments.

I agree with your overall point–cost needs to be addressed. Personally, I’m happy with the pay I get as a part-time Lecturer at UCD. I just wish there were more job security (as far as not knowing from year to year if I’ll be assigned any classes).

I have to agree with KSmith, Frankly.

As a consultant and very experienced IT administrator, database and web guy, I can do it all. Each job I went to I was more qualified and experienced, but the last job I was interviewed for at the county, (as a clerk), I was told I was not qualified. HR people are a joke.

After a while, your heart just isn’t in it to fight. I say this because the people or the project is more important than the money, because the stress will kill you hoping for a raise.

My pay scale when I worked in the DA’s office was comparable to an assistant DA, my bill rate much higher. Now at the UC, I make almost as much, with no SSI or benefits, twenty years later. In the Bay I make twice that. I just would rather work locally, with good people.

I think what KSmith was saying, is people like us have spent our time in the trenches, and the bosses can go away and know the place will be bulletproof until the get back because of people like us.

Yes but teaching is no longer the university’s primary mission. They don’t valie the people who teach. Even back in the 70’s I had a friend who was told teaching was a priority but when it can time for raises he got less than those who published and brought in research dollars. He was a great teacher, his students gave him the highest evaluations but he minimized the number of classes he taught, played the game by the unwritten rules and saw his salary rise. Four decades later, the university doesn’t even pretend teaching is a priority. You want tenure you need to be a rising star, do research, publish and most important, bring in big money grants.

as long as the U is top heavy with overpaid administrators and puts their money on the rainmaker professors, tutitions will rise and the freeway flyers will get squeezed more and more and paid as little as possible. It is the corporatization of the educational system. Big bucks at the very top and starve the beasts at the bottom. It’s no way to provide quality education, no way to run a country but a fine way to transfer wealth from the people who actually produce something and give it to people who actually produce nothing.

DavisBurns: Good points here. I agree that there seems to be lip service paid to the idea of teaching as a mission (at least within the UCs), but that doesn’t necessarily trickle down to those who are doing most of the teaching. Again, my own experience has been very positive in my Department, but I know that is not the case everywhere.

And my experience is admittedly only with the humanities, where emphasis is put on research, but not necessarily on bringing in big $$ grants (there doesn’t seem to be very much of that for humanities as there is in the sciences, engineering, ag, etc.). Wearing my other professional “hat,” though, I do see first-hand how grants are important and focused on to the exclusion of lots of other things.

A podcast about unionizing adjuncts, published by American Radio Works: link

As a former adjunct myself, I have received numerous mailings from the group attempting to achieve that unionization.

Thanks for the link, wdf1!