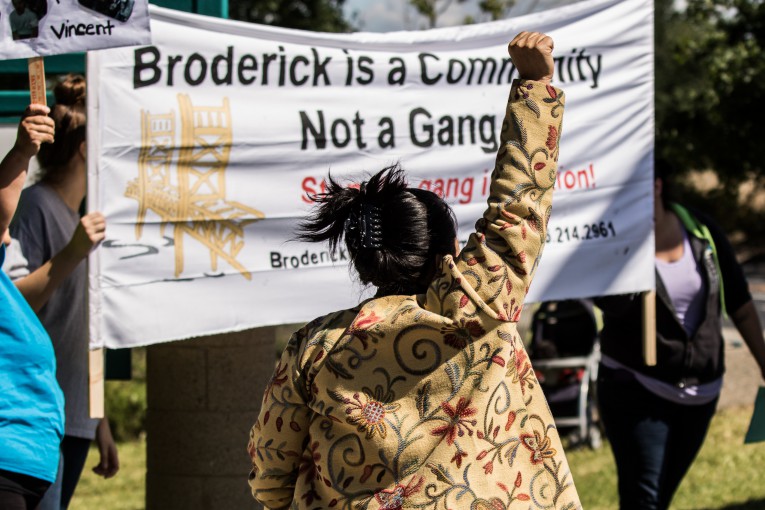

As the West Sacramento Gang Injunction appellate case moves toward a hearing, now five years after Yolo County Judge Kathleen White granted the injunction following nearly six months of trial, a new court decision further complicates the original ruling.

A ruling earlier this year in the 4th Appellate District, People v. Sanchez, changed potential rules for the admissibility of hearsay offered “not for the truth of the matter stated” when cited by an expert as the basis of his opinion. Under Sanchez, the court held “that such hearsay remains inadmissible under state law when the expert relies upon it to express opinions about specific issues in the case (as opposed to opinions concerning generalized background information).”

In the case involving the Broderick Boys, the question was whether the supposed gang members “participated or acted in concert” (collaborated) with each other to commit nuisance activity (crimes) on behalf of the gang. In so doing, Attorney Mark Merin in an August 12 briefing letter, argues, “Massive amounts of inadmissible hearsay ‘not for the truth of the matter stated,’ were admitted on this central issue by the trial court on the ground that such evidence could come in as the basis of expert opinion.”

The Sanchez court, Mr. Merin argues, “reasoned that the facts that are the basis of the expert’s opinion must be proven to be true through admissible evidence – otherwise, the alleged ‘facts’ are irrelevant and the expert’s opinion without weight.”

On the one hand, “there was much admissible evidence of convictions, crimes, and incidents involving individuals who claimed to be identified or associated with the Broderick Boys, as well as face-to-face encounters with such individuals by witnesses.”

But, as Mark Merin argues, “there were no actual witnesses who had first-hand observations or interactions which revealed the Broderick Boys’ composition and organization as a gang as defined by Engelbrecht – that is, an ongoing organization, association, or group in which ‘active’ members ‘participated or acted in concert:’ in other words, collaborated with each other on behalf of the gang entity over time.”

He noted, “This was an especially difficult problem in this case because there was no ongoing congregation of identified gang members at any particular place or time in the community, a type of collaboration which in itself can constitute a public nuisance and lay the basis for group liability.”

Instead, the Yolo County DA’s office relied upon “successive and scattered crimes as the basis of their theory that a public nuisance had been created by gang-identified individuals working in collaboration. But, the fact that various individuals committed independent crimes actually or potentially punishable under the STEP Act – the crimes our communities are plagued with – could not carry the People’s burden.”

In one example cited in the brief, Timothy Acuña drove a stolen car in the neighborhood, giving rides to some friends. Mr. Merin argues, “This type of evidence could not carry the People’s burden, even though he entered a plea, like many others, to an offense under the STEP Act. Independent gang related crime does not a nuisance make. The group gatherings were fleeting, one-time combinations – which were connected to each other only by gang culture and presumed individual propensity for crime – and therefore could not be evidence of ongoing group collaboration.”

In order to establish a public nuisance, the DA needed to “tie all the crimes together, such that each supposed gang member could be held responsible for the cumulative effect of all the other supposed members’ crimes as well as his own. Only by tying the crimes together could the People factually support its theory that there was a public nuisance, that is, a continuing violation of the public peace, caused by a collaborative group (gang), and, as well, generate a basis for finding group liability for all the individual acts thus aggregated.”

To solve this problem, “the People relied entirely upon police employed experts and the inadmissible hearsay evidence introduced through them “not for the truth of the matter stated” as well as other improperly admitted hearsay.”

Throughout the trial, attorneys for the alleged Broderick Boys gang members “objected to the inadmissible hearsay cited by the experts for precisely the reasons outlined by Sanchez.”

Mr. Merin notes, “Appellants’ counsel objected that this testimony constituted hearsay and stated ‘there’s no exception for it, and it’s being offered for its truth right now.’ The trial court denied the objection, stating that the hearsay was being offered not for the truth of the matter stated but rather ‘as the basis for his opinion.’”

He continues, “Additionally, the trial court admitted on this ground two wholesale compendia of information central to the People’s theory that the Broderick Boy gang was responsible for a public nuisance. The trial court admitted a comprehensive summary of the 108 crimes and incidents alleged to constitute a public nuisance, which included multiple layers of hearsay.”

As Mr. Merin notes, “As it turned out, on the basis of this muddled record, the trial court ruled that almost one hundred people who were not shown to collaborate in any ongoing common enterprise or on behalf of any ongoing group were collectively liable for over 108 crimes and incidents during a ten year period, crimes which cumulatively were held to be a public nuisance.”

He continues, “Why? What was the ‘pattern’ common to the scattered individual or transient group crimes? All these men (and a few women) ‘wore red’ at some time within this ten year period, and, in many cases, apparently subscribed to a violent and widespread Hispanic gang culture, or vocally claimed, with or without the commission of a crime, to be ‘Broderick Boys.’ In this case, ‘membership’ though such indicia was found sufficient. From this nominal ‘membership,’ the existence of a gang was inferred (or presumed) by the experts.

“The scant, secondhand, and spurious evidence that a gang actually existed as a result of collaboration or organization was dependent on expert testimony that used inadmissible hearsay as the basis of its crucial opinions.”

—David M. Greenwald reporting

Saying that the “Broderick Boys” are not a “gang” reminds me of this quote:

“We take strong exception to them being classified as a gang. They’re a motorcycle club, not a gang.”

http://archive.jsonline.com/blogs/business/122863409.html

Part of the problem here is not whether they are gang, but rather whether the gang represents an ongoing nuissance. What the DA did was essential show 108 or so incidents over a ten year period and then loosely tie them together when if you looked at the incidents carefully – which we did back in 2010, it’s not clear that they are connected and it certainly questionable at times where they represented gang crimes.

A former coworker of mine ended up on that list as a result of his hotrod building hobby. Tenuous would be a generous description of any connection to a criminal group.

the problem with the gang injunction is that the da’s office showed a bunch of random crimes with a theme reed tying themselves. is there a gang in west sac? yes. does it present an ongoing nuissance, i don’t think we know

and, not only that…..which CA statute is violated by being part of any group.. whatever the “group” may be….is there now a special definition of “gang” and is it illegal to belong to such a group?

and, if so, why???

why would it be “illegal” to be a part of any group? isn’t that against the constitution, or amendments or some such..

If there is not a specific statute, then how can anyone be being accused of being a gangmember….

doxx please by those who know these latest “rules” better than I do…

PS> Broderick is a nice community of many older Russian people, and many younger Russian refugees – or is that illegal also? some perhaps may fancy themselves “group members” of some group or other, yet again, what crime is committed by being in some kind of group…

It is important to understand that it is not illegal to be in a gang – it is of course illegal to commit crimes as part of a gang. The Gang injunction is not a criminal action, it is a civil one which is why the article discusses nuisance abatement.

and yet, the gang stuff is what is constantly in the news…and the spin is always derogatory..

even the bike club reference above….I know many a biker and they are far from criminals..

many are the kindest folks one could ever run into…though they may look disheveled or tattooed up and down…most are clean and do not do drugs..

yeah, they may rev their Harleys at in appropriate moments… but even that is an exception by a handful…

and one person’s “nuisance” is another’s nirvana….if not a crime, why do others make it sound like a crime???

I’m speaking specifically to the issue of the gang injunction. There are criminal aspects to gangs and criminal charges associated with committing crimes as a gang member.

yes, I get your clarification David. I also hope you understand why I question…not only have I gotten out of the loop in recent years, but there is a ton of rascism in many actions such as what you share in the commentary….we have way too many unfair and discriminatory rules and regulations…and way too many laws of various kinds that are used inappropriately and unfairly….I often do not look at something in a vaccum….I know that bugs a lot of people..

In that area I have heard there are more Russian gang members – kind of unusual as they are not even a protected class – while typically most gang members these days are of protected minority groups