For years the issue of land use seemed to disappear from the radar of the city. The economy was down, applications were not happening, and for several election cycles, issues such as budget and finance seemed to predominate. But as the great recession faded and pent-up demand met with the need for economic development and new housing for students – land use issues have exploded back onto the scene.

The first battle was waged over Nishi and, unlike the two previous Measure J projects – Covell Village and Wild Horse Ranch, Nishi was fought to a veritable draw with about 600 votes separating No from Yes.

The defeat of Nishi has emboldened vocal critics of development, while leading some supporters to believe that Measure R is what stands in the way of Davis and good planning.

While it is somewhat tempting to believe that, what we have seen in recent months leads me to believe that Measure R is only a symptom of the problem, not the problem itself. I say that as a strong believer in Measure R and the concept of citizen-based planning. However, in the last few months I have come to believe that the entire planning process is toxic.

There is, in fact, a long and growing list of community pushback against infill projects. We can start with Paso Fino, then go to Trackside, Sterling, the Hyatt House Hotel, and now perhaps Lincoln40.

For those who believe that the problem is infill and if we simply opened up the possibility of developing on the periphery, things would be easier – I have to disagree. Look first at the battle for Nishi and then look at the immediate pushback against the idea of housing at Mace Ranch Innovation Center (MRIC). There is no reason to believe that MRIC with housing would be any less contentious than any of the other developments.

Something needs to be made clear here as well – with a lot of these projects there are some legitimate concerns. Certainly, with Paso Fino, the idea of swapping the greenbelt and developing it was probably ill-considered. With the initial Trackside project, the idea of six stories was a problem.

So, I do not want to convey the message that there have not been legitimate concerns about at least some of these projects. Likewise, I had a problem with Mission Residence which preceded these other disputes – in that case you had a long process where the neighbors and city laid out goals for redeveloping the B St area and then, a few years after that process, the city allowed the developer to violate those agreements.

That was an egregious abuse of process that we really can say we have not seen before or since. At least in my view.

However, what has evolved in the last six months to a year is a very contentious and toxic process for all involved. There are legitimate reasons for neighbors to have concerns over impacts of projects, but at times we forget there is a public process that has to play out with give and take.

The Hyatt House has been another recent example. The neighbors have laid out a list of concerns, although I think some of them have been overplayed. For example, I do not believe that the safety issue is a legitimate concern. For most neighbors, neither is the privacy issue.

Nevertheless, the Vanguard visited the home of a person who has a legitimate concern about privacy issues. The developers have attempted to address some of these concerns through trees and now screening mechanisms.

At the end of the day, I think a lot of the neighbors simply do not want a hotel there. That will ultimately be the call of the city council. Part of what we do not know is how the city council will respond to any of these disputes – because none except Paso Fino have gotten to the council yet.

Part of the overall strategy of the council seems to be to look at the bigger picture. We will see that at play with the General Plan update, as the council seeks community input.

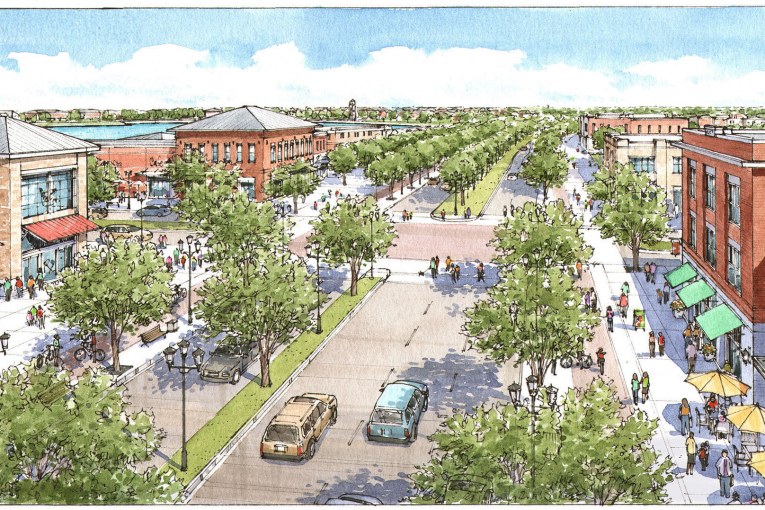

Another strategy seems to be trying to create a more predictable planning environment. On Tuesday will be the discussion of Form-Based Codes.

The Form-Based Codes Institute notes, “Form-Based Codes foster predictable built results and a high-quality public realm by using physical form (rather than separation of uses) as the organizing principle for the code. A Form-Based Code is adopted into city or county law as regulations, not mere guidelines. Form-Based Codes are an alternative to conventional zoning.”

Staff writes, “Form-Based Codes focus primarily on the look and feel of the built environment emphasizing a high-quality public realm. This is accomplished by prescribed massing and form in how buildings relate to one another through the establishment of various scales of block patterns and street types.

“Land use receives less emphasis and is secondary to form. This differs from the focus of conventional zoning where land uses are segregated and intensity of development is established through parameters such as, density, floor area ratio, setbacks, parking standards, traffic level of service, and general height and area regulations.

“The conventional zoning code creates the regulatory framework for development that is oftentimes combined with advisory design guidelines that attempt to inform the built environment. Form-Based Codes replace conventional zoning codes and design guidelines serving as a regulatory tool to implement a community plan or vision based on desired forms of urbanism.”

According to the Form Based Codes Institute, there are five main elements of Form-Based Codes which are as follows:

- Regulating Plan – A plan or map of the regulated area designating the locations where different building form standards apply.

- Public Standards – Specifies elements in the public realm: sidewalk, travel lanes, on-street parking, street trees and furniture, etc.

- Building Standards – Regulations controlling the features, configurations, and functions of buildings that define and shape the public realm.

- Administration – A clearly defined and readily understood application and project review process.

- Definitions – A glossary to ensure the precise use of technical terms.

While looking toward new innovations should always be encouraged, perhaps this type of approach will alleviate tension between old designed neighborhoods and new designed infill. On the other hand, I think there are some more fundamental issues at work – that we see played out in the tension between development in town and those who wish to see new student housing accommodated on the campus.

It is clear that this clash is going to be the real challenge for the city going forward, and attempting to deal with vexing issues such as revenue and housing.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

“It is clear that this clash is going to be the real challenge for the city going forward and attempting to deal with vexing issues such as revenue and housing.”

It never occurs to you that revenue and housing are only so vexing because the city isn’t going forward? Too easily vexed for a city that claims to be so smart.

How is a hotel that charges $250 per night, seasonal rates, going to benefit the lower income folks of Davis, and more importantly, its Albany Ave. neighbors?

How about $700,000 in TOT to the city which will help the city pay for infrastructure and services?

People who stay in hotels buy dinner and perhaps tchotchkes. People who stay in nice hotels buy nice dinners and tip. Lower income people often work in service industries.

Great. Why do I have the feeling that this is ultimately another way to force development into places it doesn’t belong (without actually admitting it)?

Maybe we need another pyramid diagram (or two), before we’re all convinced?

Have you ever considered that the problem is that you readily jump to that conclusions?

Education is a wonderful thing.

Form based codes

Mark: I would have to ask what the REASON is, to change the current approach. Is the goal to approve “less” development?

Shouldn’t the first question be: what is form-based codes and what changes they will bring?

David:

I think my question is better, but it is closely related to your question. In other words, what “problem” are we trying to address?

But, you and Mark make valid points. There’s nothing wrong with looking at other methods, as well. Perhaps I’m over-reacting, based on all of the other recent development proposals that are being considered (and pushed by some).

Thank you for proving the point of my article

The problem may be in your mirror

Well now, that’s not very nice, is it? Especially since I already acknowledged that I probably over-reacted.

David Greenwald said . . . “The first battle was waged over Nishi and, unlike the two previous Measure J projects – Covell Village and Wild Horse Ranch, Nishi was fought to a veritable draw with about 600 votes separating No from Yes.”

David, I respectfully disagree with you.

— The battle over Nishi was still in its embryonic state when the battle over Davis Innovation Center resulted in the denise of that project (see LINK).

— Nishi was also preceded by the CEQA lawsuit over the Embassy Suites Hotel/Conference Center,

— As well as the intense Paso Fino skirmish, and

— The 11-unit development south of Montgomery Boulevard under the provisions of Yolo County’s Ag Clustered Housing Ordinance.

Preceded by conflicts over Wildhorse Ranch, Covell Village, Measure J, Wildhorse and Mace Ranch. There have been other ideas over the years that have been rejected too but are less high profile. Mike Corbett’s proposal South of Davis, Redevelopment of Olive Drive, a sports complex north of Covell. I’m sure there were others even before that going back all the way to when Jerry Adler was on the CC. History didn’t end when the Berlin Wall came down as some suggested it would and Davisites opposing growth probably goes back as far as Malthus or at least to Revelle and Ehrlich. Picking a starting point is a foolish endeavor. Just as picking a new system for decision making won’t end it. The only way Davis can improve things will be to get rid of Measures J/R that constrain what the elected officials can do beyond reason. Otherwise forcing all development into the existing boundaries is a recipe for intense continued conflict as we would expect from animal models of increasing population density.

Form-based codes put teeth in what are now completely toothless neighborhood guidelines. Debacles such as the Mission Residence project would have been prevented. They neither encourage nor discourage development.

Don or anyone else who can provide an answer. Do you have any good sites for unbiased information on form-based codes. This first hit my awareness within the last year and I need to do my homework.

David Greenwald said . . . “I had a problem with Mission Residence which preceded these other disputes – in that case you had a long process where the neighbors and city laid out goals for redeveloping the B St area and then, a few years after that process, the city allowed the developer to violate those agreements.”

The B Street Visioning Process is actually another example of how the planning process is allowed to become toxic. That process was overseen by Planning Staff and at least one Council Member was very active, and the end result of the process was the assignment of Floor Area Ratios for the parcels throughout the two blocks that ranged from a low of 1.5 to a high of 2.0 (most being 2.0) except for the two lots owned by Jim Kidd which were assigned a Floor Area Ratio of 1.0. How Staff and the Council Member could allow that kind of discriminatory action absolutely “toxic.” The hearsay justification that was given to me when I asked about it was that the neighbors “didn’t trust Jim Kidd”and since he wasn’t at the meetings to defend himself they took preemptive steps to mitigate their distrust.

During the past decade I was involved in massive, simultaneous revisions of the City of Sacramento and County of Sacramento general plans. In the case of the city, it was a matter of analyzing and writing critiques of the plan on behalf of my employer. In the case of the county, it was that duty plus actually writing a section of the plan (which ultimately took something like 14 drafts). Both plan revision processes were long, tedious, excruciating, contentious and ultimately mind-numbingly boring. The outcome in both cases was massive documents that no one (even staff) could be reasonably expected to fully comprehend. By the time the plans and the attendant EIRs were complete, everyone was sick of the whole thing. But the biggest problem: by the time the plans were completed, things had changed (in some cases drastically). Many of the underlying assumptions and principles were no longer valid or at the least were badly out of date. It was as if by the time the process was done, it was time to start all over again! It gave proof to the old adage, “A plan is something from which to deviate.” So, maybe it’s time to try something else in Davis. It could be “Form Based Codes,” or something else. I don’t know if that will make things any less “toxic,” but let optimism prevail.

And here’s a casual observation. I recently had occasion to spend some time looking at “master planned” home and commercial developments in Reno. There was apparently no opposition to these projects from neighboring residents, the reason being that all were bordered by empty land. With no restraints on expansion, all the new developments were of the “leapfrog” variety, widely separated from other development by vast swaths of empty land. This of course means that there is no way to get around other than by automobile, but with nothing “next door,” there’s no opposition. The compact nature of Davis means that virtually any infill project will be contiguous with existing neighbors who will be impacted in some way, and will legitimately want their voices heard. The process will often become contentious, but that’s simply to be expected.