by Bob Schelen

by Bob Schelen

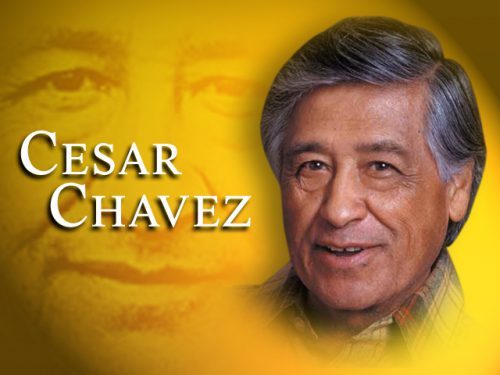

Senator Robert F. Kennedy called Cesar Chavez “one of the heroic figures of our time.”

This Friday, we will be celebrating the birthday of Cesar Chavez.

Born on March 31, 1927 in Yuma, Arizona, Cesar Estrada Chavez founded and led the first successful farm workers union in United States history. He is a symbol of hope, not only to farm workers of all ethnicities, but to all Californians who find hope in justice and peace.

Meeting challenges and obstacles head-on through non-violent tactics, Cesar Chavez helped thousands of migrant farm workers across the country. He changed the relationship between farm workers and the agriculture industry. He strengthened efforts of farm workers to have the same dignity and rights of other workers in America. His efforts impacted the entire union movement in the United States.

Chavez’s father lost his business in the 1930s during the Great Depression. Like so many others, his family migrated to California in search of work. At age 10, Cesar began a migrant farm workers’ life, traveling from farm to farm to pick fruits and vegetables during the harvests. His family lived in numerous migrant camps. They were often forced to sleep in their car. He sporadically attended more than 30 elementary schools, often encountering cruel discrimination.

By the eighth grade, he had quit school to work full time in the vineyards. The Chavez family rented a small cottage in San Jose and made it their home. In 1944, Cesar joined the Navy and served in World War II. After completing his tour of duty two years later, he returned to California.

In 1948, he married Helen; they moved to Delano, where he found work in the fields. The work entailed long, hard hours and little pay. Chavez saw injustice first hand and decided to fight for change by advocating stronger labor laws for farm workers so they could have a better life.

In 1952, Chavez met Fred Ross, who was part of a group called the Community Services Organization (CSO). Chavez became a part of the organization and began to urge Latinos and others toiling in the fields to register and vote. Chavez traveled throughout California and made speeches in support of workers’ rights, arguing that workers deserved decent lives and to be treated with dignity. In 1958, Cesar Chavez became general director of the CSO.

Four years later, Chavez left the CSO to form his own organization, the National Farm workers Association. He then joined with supporters of workers’ rights in Florida to form the present day United Farm workers (UFW) Union.

Chavez led a strike of California grape pickers demanding higher wages in 1965. In addition, they urged all Americans to boycott table grapes as a show of their support for the strike. The strike lasted five years against harrowing and often forceful opposition. When a U.S. Senate Subcommittee looked into the situation, Senator Robert Kennedy gave Chavez his total support.

Chavez preached non-violence to the strikers, even as those opposed to the grape boycott were physically abusing them. In 1968, Chavez began a Ghandi-like fast to call attention to the migrant workers’ cause. Although his dramatic act did little to solve the immediate problem, it increased public awareness of the inhumane conditions under which farm workers were forced to labor. After many battles, an agreement was finally reached in 1977 that gave the UFW the sole right to organize farm workers.

In 1973, the UFW organized a strike for higher wages from lettuce growers and during the 1980s Chavez helped call attention to the health problems of farm workers that were caused by the use of certain pesticides on the crops they tended and picked. This is an issue that continues even today in certain agricultural communities.

In 1991, Cesar Chavez received the Aquila Azteca (the Aztec Eagle), Mexico’s highest award, which is presented to people of Mexican heritage who have made major contributions outside of Mexico. Later, he became the second Mexican American to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the United States. President Clinton presented the award posthumously to Helen Chavez and six of her eight children on August 8, 1994, in Washington D.C.

When Chavez died on April 3, 1993, many believed that the UFW would also die, but that was not the case. On Chavez’s birthday anniversary in 1994, his son-in-law Arturo Rodriquez organized and led the UFW on a 343 mile march from Delano to Sacramento. This march echoed the historic 1966 march by Cesar Chavez and demonstrated that the UFW still worked on behalf on farm workers. Today, the UFW continues to win elections and negotiate contracts for farm workers.

Cesar Chavez led by example and there are many, many Californians whose lives are immeasurably better because of his work. Even as some may complain today about him and his legacy, Cesar Chavez truly made a difference.

In the 12 years, we have officially celebrated his life, a number of activities have taken place throughout the state that recognize his life, times and work. The activities include not only learning about the history of Cesar Chavez and the farm worker labor movement, but also participatory activities, such as marches and demonstrations. All this attempts to bring his legacy of hope not only to today’s farm workers, but also to people of color, immigrants, the economically disadvantaged and others that are disenfranchised from the economic well-being of life in America and California.

California was ahead of its time, some forty years ago having formed the Agricultural Labor Relations Board, in recognizing that farm workers should have the same rights as other workers. Yet, even in this century, we have seen farm workers die in the heat from too much sun and not enough water.

Such abuses have led the Legislature to pass a number of measures in recent years to more closely regulate the fields where farm workers toil so that they might live through their shifts.

The goal is to win basic rights that farm and domestic workers were denied more than 70 years ago, when the Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) administration won major reforms protecting other workers in areas like overtime, disability pay, days of rest and union organizing.

The inequality comes from a compromise FDR had to make with the so-called “Dixie-crats” that cut out much of the domestic and farm labor force, which were than African American, from the gains workers in other areas made.

Farm and domestic workers were then cut off from the labor movement. It is true there have been gains, but the poverty of the working poor, brutal working conditions, and legally sanctioned discrimination continues to stubbornly persist for a new generation of domestic and farm laborers, who are now predominantly Latino immigrants.

It is still a tough slog, as fierce fiscal battles are fought at the state and national levels. Indeed, with the new Trump Administration, we all have to be wary of losing rights, especially hard fought labor rights.

Every day, there is another issue where we must keep vigilant in protecting what we have gained. Worker rights, environmental rights, civil rights are all either in danger of being rolled back or disappearing altogether.

What better time than the birthday of one who led the fight for many of these rights to recommit ourselves to the cause of justice?