By Jeff Adachi & Yali Corea-Levy

California law provides for three common pleas in a criminal case: not guilty, guilty and no contest. In the San Francisco courts, however, an accused is not given the opportunity to plead no contest. Witness the following colloquy from a case heard last month:

THE COURT: Sir, what is your plea to violating Penal Code Section 487(a) as a felony, as alleged in Count II of the amended information?

THE DEFENDANT: No contest.

THE COURT: He has to plead guilty.

MR. ADACHI: No contest is the same as guilty.

THE COURT: Well, for the purposes of felonies, we only accept guilty pleas.

MR. ADACHI: Since when?

THE COURT: About 22 years.

MR. ADACHI: I have been here when we’ve entered no contest pleas before.

THE COURT: Not on felonies. On misdemeanors.

Although the district attorney did not object, the court refused the defendant’s attempt to enter a no contest plea.

The no-contest plea originates from the Latin phrase “nolo contendere,” which essentially means that “I do not wish to contend” the charge. Black’s law dictionary defines “nolo contendere” as “I will not contest it.” Historically, the principal difference between a plea of guilty and a plea of nolo contendere is that a no-contest plea could not be used against a defendant in a civil action. However, this difference was vitiated in 1982 when the Legislature rewrote the statute to provide that no-contest pleas in a felony case could be used as admissions in later civil proceedings, limiting the exclusion in civil cases to misdemeanor cases only.

So why should it matter to an accused? Why would it be important to an accused to say the words “no contest” rather than “guilty” if the two are treated the same? A no-contest plea more realistically represents the reason why an accused decides to end a criminal prosecution in favor of a plea bargain or settlement. It is a nationally recognized phenomenon that those accused with crimes in the U.S. often plead guilty in order to avoid a trial or to reduce the exposure that they face if convicted of the most serious offense. Jed Rakoff, a senior judge of the Southern District of New York, explained that the fear of trial, the possible consequences (i.e., jail), and loss of time often lead to guilty pleas — even where the accused maintains his or her innocence: “inordinate pressures to enter into plea bargains, appears to have led a significant number of defendants to plead guilty to crimes they never actually committed.”

Judge Rakoff cites the Innocence Project, which has shown that out of 300 people who were wrongfully convicted of rape or murder, about 10 percent had pleaded guilty. He reasons that this inconsistency can only be explained “because, even though they were innocent, they faced the likelihood of being convicted.” The same logic applies to nonlife crimes. Rakoff cites the National Registry of Exonerations (a joint project of Michigan Law School and Northwestern Law School), whose records show that of 1,428 legally acknowledged exonerations that have occurred since 1989  involving the full range of felony charges, 151 (again, about 10 percent) involved false guilty pleas.

involving the full range of felony charges, 151 (again, about 10 percent) involved false guilty pleas.

It is not difficult to see why this happens. The typical person accused of a crime combines a troubled past with limited resources. He thus recognizes that, even if he is innocent, his chances of mounting an effective defense at trial may be modest at best. If his lawyer can obtain a plea bargain that will reduce his likely time in prison, he may find it “rational” to take the plea.” In this regard, a no-contest plea acknowledges the nuances of a guilty plea through a largely symbolic act.

If in fact people do choose to plead guilty in order to avoid other potential consequences, what is the harm in allowing a no contest plea? It is largely symbolic. But then again, it gives a person who decides not to contest the charges and ability to say exactly that. And the implications in terms of inequity are well established. According to the Bureau of Justice Assistance, which tracks criminal justice statistics, between 90 and 95 percent of those accused of crime in federal and state court choose to resolve their cases without a trial.

Judge Rakoff blames overcharging by prosecutors. This has always been true, but the pressure has overwhelmed an ever increasing number of innocent defendants to plead guilty. In the words of Professor Michelle Alexander in her book “The New Jim Crow,” “[n]ever before in our history … have such an extraordinary number of people felt compelled to plead guilty, even if they are innocent, simply because the punishment for the minor, nonviolent offense with which they have been charged is so unbelievably severe … [t]he pressure to plead guilty to crimes has increased exponentially.” Alexander quotes the U.S. Sentencing Commission acknowledging, “the value of mandatory minimum sentence lies not in its imposition, but in its value as a bargaining chip.” Alexander notes that this “bargaining chip is a major understatement, given its potential for extracting guilty pleas from people who are innocent of any crime.”

And due to the overrepresentation of minorities in the criminal justice system, the pernicious effects of the practice have disproportionally powerful racial effect. For instance, felony pleas may affect the right to vote and ability to procure a job post-conviction. As Alexander notes, hundreds of years after the emancipation proclamation, “America is still not an egalitarian democracy.”

A no-contest plea recognizes the fact that many disenfranchised poor people and people of color don’t have the option of taking the risk or taking the time (which almost certainly translates to money) it takes to go to trial. So why not give them the right to declare themselves unable and unwilling to state nothing other than “I choose not to contest these charges”?

This is particularly true when a no-contest plea gives the prosecution the benefit of a conviction and is not an affirmative proclamation of innocence by the accused. Prosecutors may argue that they need the accused to say the word “guilty” as a form of allocution or to protect against a subsequent claim of factual innocence. But the “California Judges Benchguide: Felony Arraignment and Pleas” advises judges that a “plea of no-contest has the same legal effect as a plea of guilty and is subject to the court’s approval.” The guide uses no contest and guilty interchangeably throughout. And, unlike an Alford plea, where an accused proclaims innocence but decides to enter a plea of guilty, a plea of no contest is not an affirmative proclamation of innocence by the defendant.

San Francisco appears to be out of step with the rest of the state: No-contest pleas to felony charges seem to be the norm in most California counties. Out of 15 chief defenders that responded to a survey, all but one responded that no-contest pleas were not only allowed in felonies, but the norm. Given that ratio, it seems reasonable to conclude that in most counties the no-contest plea is the norm in felonies.

The San Francisco court needs to change its practice of disallowing no-contest pleas. It’s the fair, humane and just way to allow a person the dignity of entering a plea when the accused simply seeks to end the criminal prosecution.

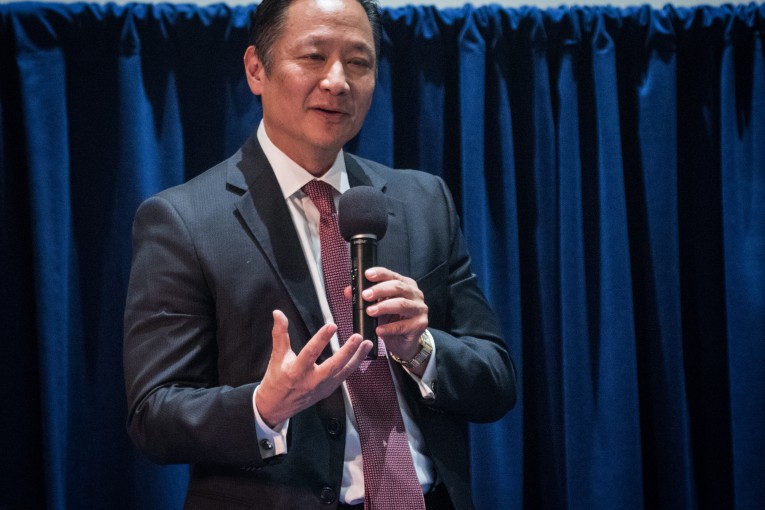

Jeff Adachi is the Public Defender of the City and County of San Francisco. Yali Corea-Levy is a San Francisco deputy public defender.

Get Tickets To Vanguard’s Immigration Rights Event

Plea bargaining takes a criminal justice issue and changes it into a business transaction. It is an icky practice.

Depends… what if you are guilty of one of the lesser charges, but innocent of the others… can you make separate pleas on each charge? If not, how does that play into First and Fifth amendment rights?

As I understand it, both amendments give someone the right to remain silent (silence is a form of free speech). Even in Court… you should not be compelled to make any plea…

How do you accommodate all the trials that would occur? 97 percent of cases plead out before going to trial. That means the trials we have represent about 3 percent of all cases. The resources needed to run such a system would be staggering.

David

I think rate depends how Judges are instructing jury during the trial . I studied some criminal cases including Dev’s case from Yolo than is a flexible matter .

I’m sure Mr. Adachi will be pleased to learn about Yolo County where they do not overcharge people and everyone is offered their day in court.

I will compliment Judge Rakoff on the correct usage of the term “overcharge” which means to discourage people from going to trial. Many people here in Davis seem to be ignorant of this and use “overcharge” when “Prosecutorial Discretion” would be the phrase they are looking for.

There seems to a complete lack of logic in this article. “If in fact people do choose to plead guilty in order to avoid other potential consequences, what is the harm in allowing a no contest plea? It is largely symbolic. But then again, it gives a person who decides not to contest the charges and ability to say exactly that” I can see how the judge would not want to cosign the implication that they are a corrupt actor in a corrupt transaction.

“I will compliment Judge Rakoff on the correct usage of the term “overcharge” which means to discourage people from going to trial. Many people here in Davis seem to be ignorant of this and use “overcharge” when “Prosecutorial Discretion” would be the phrase they are looking for.”

You have this wrong. What’s happened in Yolo is not simply overcharging, but unreasonable plea offers that have resulted in people feeling they have little to lose by going to court. This is embodied in the low conviction rate in jury trials.

I am not wrong David,

“Prosecutorial discretion is the authority of an agency or officer to decide what charges to bring and how to pursue each case.” Which is exactly what you are complaining about. Or, if you prefer, here is a definition from a separate source.

“Prosecutorial discretion refers to the fact that under American law, government prosecuting attorneys have nearly absolute powers. A prosecuting attorney has power on various matters including those relating to choosing whether or not to bring criminal charges, deciding the nature of charges, plea bargaining and sentence recommendation. This discretion of the prosecuting attorney is called prosecutorial discretion.”

Adachi complains because there are too many plea bargains and you complain because there are not enough.

Yes, you were wrong and failed to address my point but also failed to understand that the nature of the complaint in Yolo is not simply “overcharging” but also “unreasonable offers.” Adachi is not complaining that there are too many plea bargains and I’m not complaining that there are not enough. You’re completely failing to understand the nature of the complaint here.

David:

“Yolo is not simply “overcharging” but also “unreasonable offers.”

“unreasonable offers” is a function of “Prosecutorial Discretion”.

“overcharging” would mean a very high plea bargain rate which Yolo does not have though other jurisdictions do. I have been a consistent critic of high plea bargain rates. You cannot have “overcharging” and low plea bargain rates, they are mutually exclusive.

Yes you can. Because plea rates are not just a function of the charges, they are also the function the offers given by the prosecution. The reason they are not taking the pleas in Yolo is because the offers are not reasonable and the defense takes its chances and takes the cases to trial. Once there, the statewide acquittal rate is something like 16 percent in a trial, in Yolo, it’s 42%. That number alone backs up what we are observing on the ground.

To illustrate this point, here’s from a case we covered, vague up because I often get told stuff by the defense that they don’t want attributed.

But the basic facts were that the guy was charged with several robbery charges and faced 10 years in prison. It was a ridiculous overreach and should have been petty theft.

According to your theory, this would induce a plea agreement except that the DA’s offer was six years.

The defense is like forget that. Why take six years when I have a decent chance of getting a better outcome going to trial.

So they did, the jury convicted the guy of the lesser charge of petty theft and he was out with time served.

Perfect example of how your theory is completely wrong and you have failed to account for the key variable of the reasonable offer.

David, your example confirms that the DA is NOT “overcharging”. Overcharging is defined as adding extraneous charges for the purpose of driving a plea bargain. Your example shows a defendant going to trial which would indicate that a plea bargain did not drive the charging decision.

if the DA just likes to add a whole bunch of charges and is content to go to trial on them then that is not “overcharging”, that is “Prosecutorial discretion”.

What you consider to be a “reasonable offer” may not be viewed that way by the victim. I listened a discussion of timeshare sales practices once. They had what they called the “puke price” and the “nosebleed drop”. Overcharging is similar.

“Overcharging, in law, refers to a prosecutorial practice that involves “tacking on” additional charges that the prosecutor knows he cannot prove.[1] It is used to put the prosecutor in a better plea bargaining position.”

You’re being ridiculous. What term do you use to describe charging a defendant with more severe charges than warranted? You’re turning this into a semantics debate.

“What term do you use to describe charging a defendant with more severe charges than warranted?” Abuse of “Prosecutorial discretion”. I’ve said that numerous times. Here it is again.

“Prosecutorial discretion refers to the fact that under American law, government prosecuting attorneys have nearly absolute powers. A prosecuting attorney has power on various matters including those relating to choosing whether or not to bring criminal charges, deciding the nature of charges, plea bargaining and sentence recommendation. This discretion of the prosecuting attorney is called prosecutorial discretion.”

“semantics debate” There are very specific definitions for each of these terms. For whatever reason you insist on using them incorrectly. If you can find a source that defines “overcharging” as “charging a defendant with more severe charges than warranted” please cite it.

You’re wasting my time.

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

It is a waste of his time to debate someone that challenges his fixed-mindset. But you are not wasting the time of most others reading the exchange. It was a very good exchange.