By Ali Winters

At the first checkpoint at Tennessee Prison for Women, there was a large, scrolling television screen behind the desk displaying the image of two pairs of hands – one pair with a key and one pair in handcuffs. The message read, “You can either be one of us or one of them.” I had been working in the facility for less than a year, but this message exemplified an uneasiness I had long felt without articulating: The prison’s façade of “rehabilitation” masked a system so blatantly punitive and practically ineffective that the choice itself was impossible, offensive, and encapsulated all that was wrong with this failed iteration of the carceral state.

As a senior clinical therapist at the prison, I provided mental health services to women in solitary confinement. Initially, and admittedly somewhat idealistically, I viewed my job as stabilizing my patients, improving their ability to cope, and ideally moving them toward healthier living and functioning as part of a multidisciplinary team.

Over time, however, I found myself in the unfortunate position of “sounding board” – of becoming a receptacle for the dark energy that saturated their life experience in agonizingly inhuman conditions.

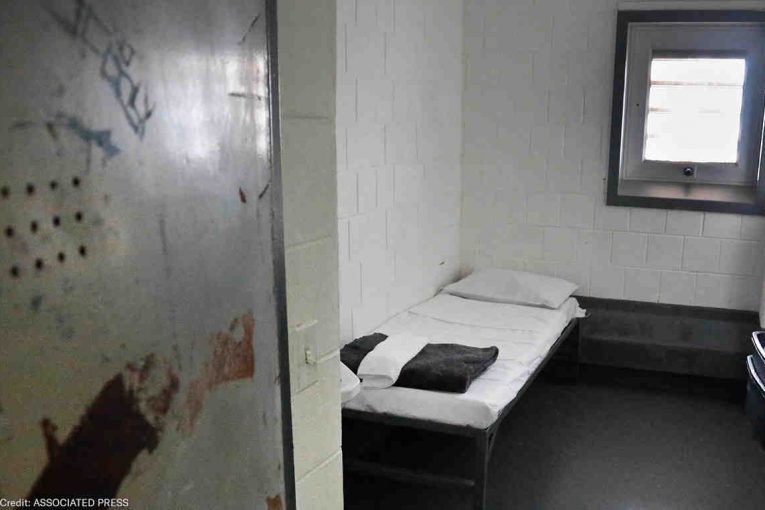

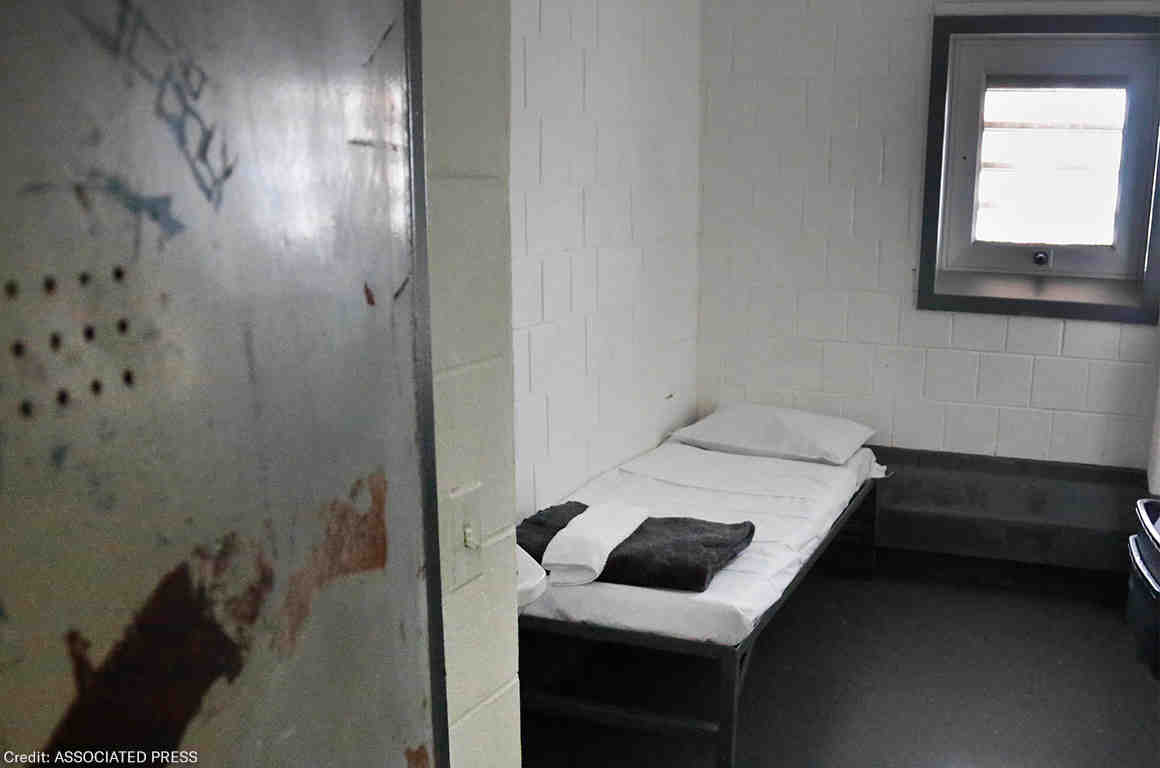

Confined to a cell the size of a parking space for more than 23 hours a day, my patients were bombarded by unremitting florescent lighting and constantly deafening sounds, both of which impaired proper sleep and eroded their psychological well-being. The architecture of punishment was also a major factor. High ceilings and concrete floors ensured they found no normalcy, and were either too hot or too cold. Cells were also arranged, or designed, in a way that made it next to impossible for them to have effective communication between them and, outside of incidental contact during escorting, they by course experienced no human touch at all.

Most of my patients came and went from solitary as part of a determinant stay of just a few days for minor rule infractions. They quickly resumed their lives on the main compound once released. But, some women in solitary confinement were not so lucky. These women, for a variety of reasons, were barred from joining the general prison population for months, years, and even decades. This is what people mean  when they say “prolonged solitary confinement,” and it is as devastating as it sounds.

when they say “prolonged solitary confinement,” and it is as devastating as it sounds.

Some women were placed there because of behavioral problems, others by virtue of their sentence, still others for their own protection. A few, called “safekeepers,” were there out of a need for proper treatment of a medical or mental health condition. These women – and the institutional response to them – made that choice at checkpoint so hard for me to answer.

The women with whom I worked were part of the 80,000-100,000 people enduring solitary confinement every day and hundreds of thousands of people enduring solitary confinement every year in this country, an increasing number of whom are women due in part to the swelling numbers of women entering the US correctional system. Under the pretext of “safety” and “security”, many prisons and jails across the country house people in prolonged solitary without any due process or independent oversight. The lack of accountability breeds bad practices and violations of rights and dignity. In other words, these women endure excessive and often retaliatory placement in solitary that can last for years or decades without any real justification. The human mind is not equipped to tolerate that kind of extended isolation, especially when the environmental conditions mix both sensory deprivation and sensory overload. While some incarcerated women had a capacity to withstand it better than others, in the end, no one escaped without being changed by the experience.

In addition to the trauma they suffered, at base these women felt ignored and discarded. Like ghosts searching endlessly for a clairvoyant to interpret their needs, they felt abandoned by each person passing their door.

The direct result of this perpetual cycle of cresting and falling hope was an ever-increasing agitation and irritability. They yelled and banged on their doors. They paced for hours inside their cell. They picked fights with each other and staff. As these symptoms progressed, they entered an existential crisis, vacillating between a semi-conscious state of detached numbness and desperate attempts to feel something. To feel anything. Many became fixated on seemingly insignificant things, responding dramatically to even the slightest of provocation. Some would brood for days over a perceived injustice, then spend weeks, or even months, carefully planning a retaliatory strike. Still others would turn inward, capitulating to the despair and isolating even further.

Deprived of so much, and in the absence of something to occupy their minds or somewhere constructive to channel that negative energy, these women would create their own distraction-rich reality. And because they believed they had nothing left to lose, those distractions would frequently escalate into violence. Prolonged solitary confinement doesn’t make prisons safer. Quite the opposite actually; prolonged solitary confinement creates the very violence prisons claim they are trying to control.

During my time working in the prison, I often reminded myself that as painful as it was for me to witness this kind of suffering, I could disconnect from it at any time. My patients had no such luxury.

When I accepted a faculty position at Tennessee State University, I experienced some ambivalence about leaving the prison. Frankly, I believed my job with these women was incomplete. So, as has become my charge and calling, I became an advocate for them on the outside. Back to the question of whose “side” I chose, in the end it was the side of my patients. I remain hopeful that the other side, the side in power will soon find the wisdom and impetus to move toward safer alternatives to prolonged solitary confinement. The very rights and health of incarcerated women are on the line.