By Danielle Silva

By Danielle Silva

In a time where progressive prosecutors are becoming a national movement, several organizations came together to create a document outlining abolitionist principles and strategies titled “Abolitionist Principles & Campaign Strategies for Prosecutor Organizing.”

Community Justice Exchange presented the document at a webinar on Nov. 11, 2019.

The presentation began with words from Mariame Kaba, the founder and director of Project NIA and co-founder organizer with Survived and Punished New York. She noted how, in 2014, many police-related shootings had gained attention and these incidents were not addressed by the prosecution.

During that time, Kaba and other individuals engaged in a campaign after the police shooting and cover-up of Laquan McDonald involved Cook County state’s attorney Anita Alvarez. Their campaign #ByeAnita spoke out against her poor practices as a prosecuting attorney as she was running for her third term in office. Alvarez was replaced by Kim Foxx in 2015, a person regarded as a progressive prosecutor.

Kaba wanted to address that, while they did not support the Alvarez, that didn’t mean they supported Foxx.

The Abolitionist Principes for Prosecutor Organizing was created to help address the distinction between supporting progressive policies and progressive prosecutors.

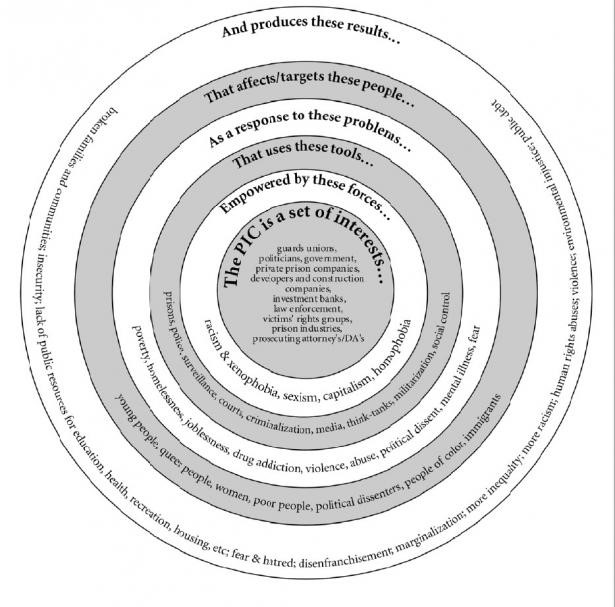

Abolitionism, at its core, focuses on reducing the Prison Industrial Complex or “the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems.” The document, made by Community Justice Exchange, Court Watch MA, Families for Justice as Healing, Project NIA, and Survived and Punished NY, wanted to clarify how abolitionism didn’t just support progressive policies but seeking to reduce the power of the PIC, which included the role of prosecutors.

to economic, social and political problems.” The document, made by Community Justice Exchange, Court Watch MA, Families for Justice as Healing, Project NIA, and Survived and Punished NY, wanted to clarify how abolitionism didn’t just support progressive policies but seeking to reduce the power of the PIC, which included the role of prosecutors.

Kaba explained that the document isn’t supposed to be taken as law but should be seen as establishing abolitionism as a set of needs and of values.

Jamani Montague, National Membership Coordinator of Critical Resistance, presented some definitions to help better understand the document.

Montague reiterated that the definitions aren’t static but are working definitions that allowed them to articulate what abolition meant.

“Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) Abolition is a political vision with the goal of eliminating imprisonment, policing, and surveillance and creating lasting alternatives to punishment and imprisonment,” Montague stated.

She elaborated that abolition should be seen as a practical organizing tool and a long-term goal. While there are no perfect solutions, they argued that abolitionist strategies can work on undoing the current system that has given power to the PIC that should be given to the people.

Montague also explained the difference between Reformist reform and Non-Reformist reform. Non-reformist reform, also known as abolitionist reform, “is a practical effort or step that changes aspects of the prison industrial complex towards completely dismantling the system.” Reformist reform, on the other hand, addressed “immediate issues… but grew the scope of the PIC.”

To determine if a policy is non-reformist reform, the policy must: reduce funding to police; challenge the notion that police increase safety; reduce tools/tactics/technology police have at their disposal; and reduce the scale of policing.

Prosecutors are seen as individuals who have a large role in putting individuals in prison and, as such, non-reformist reform encourages prosecutors to have less power and authority.

“Individualizing police violence or prosecutorial harm creates this false distinction between good prosecutors and bad prosecutors, and good police and bad police rather than challenging the assumption that there’s a system that these folks are playing their role in,” Montague stated.

“It needs not to be seen as an individual issue but a systemic one,” she added.

They used solutions to overcrowding in jails as examples in comparing non-reformist and reformist. Reformist argues for more jail construction and building new jails as old ones are closed as a solution to overcrowding. Non-reformist argues for reducing the jail population and closing more jails.

Rachel Foran, Tactical Organizing Director of Community Justice Exchange, spoke next, introducing the document.

She reiterated the idea that prosecutors should be seen as law enforcement and part of the prosecution, even if they have progressive politics. While they may have policies that seem attractive in helping individuals who are incarcerated, the document states, “Prosecutors are not social workers… They cannot and should not provide services to people who are in need.”

“Resource shifting from carceral prosecution to carceral social services is not de-resourcing. Social services become another punishment tool of the punishment system whether housed in or mandated by the prosecuting office,” the document states.

Abolitionist principles state that the prosecuting office must be stripped of its power and resources and cannot be co-governed with/by community organizations.

While there isn’t one path to the answer, the document outlines how abolitionist campaign strategies should first focus on increasing the number of people who share a vision for abolition, raising awareness, shifting the narrative away from stigmatizing language used in traditional punishment narratives, and encouraging “Mutual Aid.”

Mutual Aid is “a form of political participation in which people take responsibility for caring for one another and changing political conditions, not just through symbolic acts or putting pressure on their representatives in government, but by actually building new social relations that are survivable.”

These strategies are a base for higher goals for abolition. In focusing on the prosecution office, they encourage electoral organizing to remove officeholders and staff in the prosecuting office committed to status quo punishment and harm, shifting office and policy culture to hold elected prosecutors accountable to implementing promised policy changes, shrinking the systems of harm by implementing policies that reduce the reach and influence of the prosecutor, and pressuring state and local actors to prioritize funding for community-based resources that produce safety and well-being.

These steps contribute to an overarching goal to address the goal of shrinking structural power.

The document also provides a section explaining examples of demands organizers may need to utilize in their local context, such as de-resourcing, funding the community, rejecting hi-tech interventions that reinforce racism, rejecting and disrupting media narratives that use individual cases to applaud the role of the prosecutor and obscure the daily grind of prosecutions, and demanding transparency in the prosecutor’s office.

Two examples were provided by other speakers in the context of using abolitionist principles with the prosecutors who claim progressive policies.

Woods Ervin of the San Francisco Chapter of Critical Resistance stated how he had been a part of the No New San Francisco Jail Coalition.

In 2015, the Board of Supervisors rejected an $8 million jail construction proposal from the state and established City Workgroup to investigate alternatives to depopulate the jail after years of No New SF Jail Coalition organizing. The money was instead used for the Jail Replacement Project to research community-based alternative solutions to decrease San Francisco’s reliance on imprisonment from a group of

In June 2016, San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón, the now-former SF DA who also took a stance against the proposed jail, began “backroom deals” for a partially locked mental health facility run by Sheriffs known as the Behavioral Health Justice Center.

“The Coalition was using the JRP to push for decarceration, expansion affordable housing, and community-based mental health care,” Ervin stated. “Gascón derailed and attempted to push funding for this project lead by his office.”

The JRP ended in a stalemate but the Coalition continued to organize against the construction of new jails. Ervin explained that Gascón’s stance as a “progressive prosecutor” and a prosecutor for decarceration made it difficult to limit his power as a prosecutor in a city like San Francisco.

A representative from Court Watch MA gave another example of speaking out against unfair practices against progressive prosecutors while not immediately showing support for the prosecutor’s office.

The policies stated in the document have helped them navigate how they interact with Boston District Attorney Rachel Rollins, considering supporting her policies that are non-reformist such as decarceration policies while also establishing they don’t support the role of a prosecution office.

DA Rollins received racist attacks due to being a black, female district attorney. While Court Watch MA continued to push DA Rollins to hold up to her promised decarceration policies, they also made sure to push back against the racist comments that targetted DA Rollins.

She stated that she looked beyond simply the policies of Rollins but the prosecuting office as a whole. The representative recommended looking into the details of the policy to make sure to see the extent of decriminalization that the policy contains as some policies may only apply to certain cases. One such instance is the idea of “need” – she argued that the prosecuting office deciding what a person needs should not be something the prosecuting office does.

Court Watch MA has also released a report called Rhetoric, Not Reform: Prosecutors & Pretrial Practices in Suffolk, Middlesex, and Berkshire Counties that explored pre-trial reform and how practices promised from prosecutors often are not kept.

In the short question and answer portion, the speakers of the webinar pointed out that solutions should be focused on community healing and community advisory. Committees should not be working with prosecutors as, simply because of how the system is set-up, prosecutors will always have committees subject to their policies.

Working with towards opportunities for communities should be the emphasis and, if there are non-reformist policies like decarceration that a prosecutor pushes for, the community should hold them to it. They encouraged individuals to continue the conversation and organizing interventions.

This is a really good article