by Anika Khubchandani

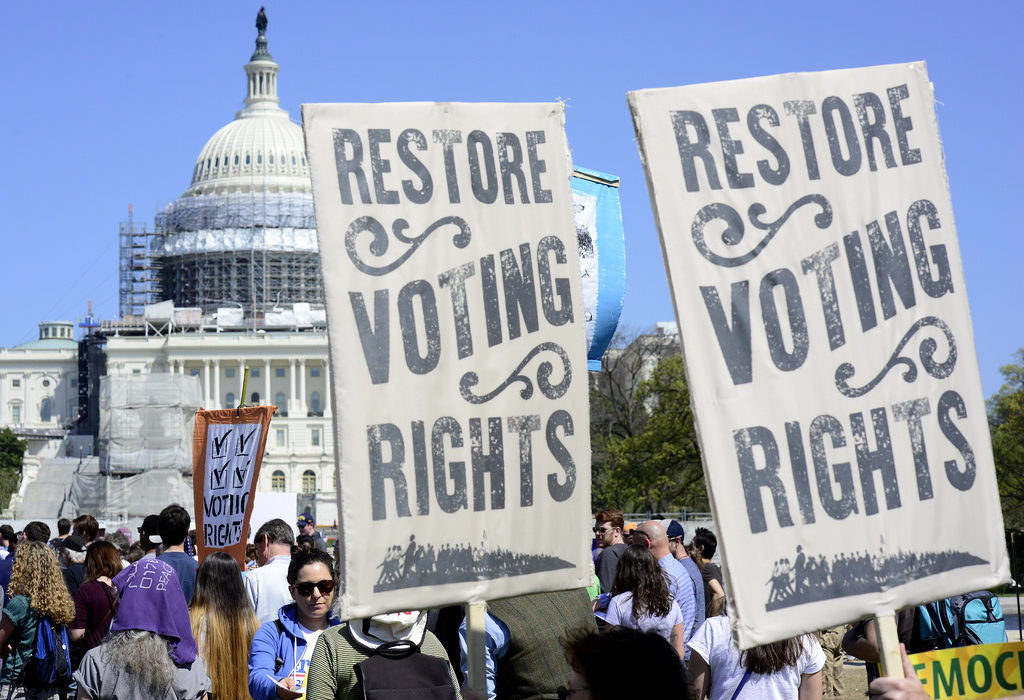

FLORIDA – In 2018, the people of Florida authorized an amendment to the State Constitution, restoring the voting rights of many ex-felons. Now, in 2020, a federal court nullified the intent of the change.

Amendment 4 began as a voter initiative and then the Florida legislature passed Senate Bill 7066 to implement this amendment. But Friday, September 11, 2020, the US Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit narrowly overturned that decision in a 6-4 ruling.

Now, ex-felons can vote, as the amendment intended, but they must complete all terms of their criminal sentences prior to regaining their right to vote, including probation, and payment of any fines, fees, costs, and restitution.

Equal rights proponents disagreed with the payments requirement and argued that this condition is in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment and the 24th Amendment on the grounds that it imposes a tax. And, they say the laws governing felon re-enfranchisement are vague, and that the state of Florida has denied these felons due process of law.

The US Court of Appeals, however, found Florida’s felon re-enfranchisement scheme to be constitutional. Therefore, the Court reversed the judgment of the district court and vacated the  disputed sections of the permanent injunction.

disputed sections of the permanent injunction.

Chief Judge William Pryor delivered the opinion of the Court and divided his discussion into three sections.

First, he explained that SB 7066 does not violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Then, he demonstrated that the laws do not levy a tax on voting, which would be in violation of the 24th Amendment. Finally, he rejected the arguments that the laws in question are vague and that the state of Florida has failed to provide due process to the felons.

Pryor found that Amendment 4 and SB 7066 do not violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, citing Richardson v. Ramirez as precedent. Since this court case finds that the Equal Protection Clause in Section 1 of the 14th Amendment does not forbid the practice of felony disenfranchisement, Pryor explained that “the Equal Protection Clause permits States to disenfranchise all felons for life, even after they have completed their sentences.”

Therefore, he said, this appeal must consider the limits the Equal Protection Clause places on restoring the rights of felons. According to Shepherd v. Trevino, the Constitution grants each state discretion with regard to the disenfranchisement and re-enfranchisement of felons.

Florida has discretion with regard to disenfranchisement and re-enfranchisement and is agreeing to restore some felons to the franchise, based on the financial obligations of their criminal sentences.

However, this discretion is not absolute. According to Pryor, “states cannot rely on suspect classifications in this area” and with the “absence of a suspect classification that independently warrants heightened scrutiny, laws that govern felon disenfranchisement and reenfranchisement are subject to rational review basis.”

Since the only classification in question involves felons who have completed all the terms part of their criminal sentences and those who have not, “this classification does not turn on membership in a suspect class,” the court reasoned.

The requirement is only based on financial terms and disregards race, religion, and national origin, said Pryor, making it clear that “the state of Florida withholds the franchise from any felon, regardless of wealth, who has failed to complete any term of his criminal sentence — financial or otherwise.” Since the classification is not suspect, the requirement must be reviewed by the rational basis test.

The rational basis review test, Pryor continued, requires the statute or ordinance in question to have a legitimate state interest and a rational connection between the statute or ordinance’s means and goals. Florida has two relevant interests here.

He cited one reason as Florida’s interest in disenfranchising convicted felons, and even felons who have completed their sentences because of their lack in judgment. In addition, Florida also has an interest in restoring the vote to felons once they are “fully rehabilitated by the criminal justice system.”

These two interests go hand in hand and are “legitimate goals for a State to advance,” stated Pryor.

Judge Jordan dissented with the majority opinion, arguing that the only interest the state has is in “punishment and debt collection.”

Pryor stressed that “there is no evidence of any kind of animus toward indigent felons” motivating the voters and legislators of Florida to condition re-enfranchisement on the completion of all terms of the criminal sentences of felons. With Amendment 4 and SB 7066, Florida is attempting to make it easier for felons to regain the franchise.

Overall, Pryor disclosed that “under this deferential standard, Florida’s classification survives scrutiny.”

The next issue Pryor addressed was that Amendment 4 and SB 7066 do not violate the 24th Amendment which forbids taxes on voting in federal elections.

The felons’ argument presents two questions, “first, whether fees and costs imposed in a criminal sentence are taxes under the 24th Amendment, and second, if fees and costs are taxes, whether Florida has denied the right to vote ‘by reason of’ the failure to pay fees and costs.'”

Pryor cites United States v. Constantine to showcase how the Supreme Court differentiates taxes from penalties. To sum it up, Pryor says “if a government exaction is a penalty, it is not a tax,” because the concept of a penalty means a punishment for an illegal act. Court fees and costs incurred by a criminal sentence are in line with this definition and are part of the State’s punishment for a crime and therefore do not qualify as taxes.

Pryor admitted that “one purpose of fees and costs is to raise revenue,” as is the goal of taxes; however, “that does not transform them from criminal punishment into a tax.”

The second argument raised by ex-felons’ lawyers is why Florida does not deny the right to vote “by reason of” failure to pay a tax for all voters. In fact, the state of Florida does not deny the right to vote “by reason of” failure to pay a tax. The 24th Amendment is unable to be invoked when the right to vote has been constitutionally forfeited. Since “disenfranchised felons have lost their right to vote, they…have no cognizable 24th Amendment claim until their voting rights are restored.”

Lastly, Pryor asserted that Florida has not violated the due process clause. Even though the district court failed to decide on whether Amendment 4 and SB 7066 violate the due process clause, the district court still declared the laws in question to be unconstitutional “as applied to felons who cannot determine the amount of their outstanding financial obligations with diligence.”

The Plaintiff ex-felons argue that the Florida laws should be voided due to vagueness, and that these laws deny them procedural due process.

On the vagueness issue, Pryor affirmed that “the challenged laws are not vague.” Felons and law enforcement can study the relevant statutes and determine what specific conduct is forbidden.

Plaintiffs also maintain it is difficult to discern whether a felon has completed the financial terms of their sentence. Pryor demonstrates that these concerns are not due to vague law, but from specific situations that make it difficult for felons to “determine whether an incriminating fact exists.”

The Plaintiffs also state that Florida’s every dollar policy makes the challenged laws vague, but Pryor showed that this policy is designed to narrow “the scope of criminal liability” and therefore cannot be vague.

On the issue of due process, the ex-felons claim that they have a “liberty interest in the right to vote and argue that Florida has deprived them of that interest without adequate process.”

Since they were deprived of the right to vote through legislative action and not adjudicative action, the legislative process “gave the felons all the process they were due before Florida deprived them of the right to vote and conditioned the restoration of that right on completion of their sentences,” asserted Pryor.

Circuit Judge Lagoa concurred with Chief Judge Pryor and reiterated the fact that “there is nothing unconstitutional about Florida’s reenfranchisement scheme.”

Lagoa stressed that the “Court must respect the political decisions made by the people of Florida and their officials…regardless of whether [the Court] agrees with those decisions.” Even though the current trend is towards re-enfranchisement, the Court is tasked by the Constitution to administer “the rule of law in courts of limited jurisdiction.”

Since a core dispute in this case is whether Florida’s felon re-enfranchisement scheme should be subject to a form of heightened scrutiny or mere rational basis review, Lagoa clarified that heightened scrutiny is inappropriate “because Florida provides indigent felons alternative avenues to attain reenfranchisement.” For example, felons who are unable to meet their legal financial obligations can have their LFOs “converted to community service hours.”

Again, Lagoa added, since indigency is not a suspect class, it does not “implicate a suspect classification and therefore does not trigger heightened scrutiny.” The alternative treatment of indigent felons is not due to their indigency. Instead, it is for a “legitimate state interest” and therefore “treated differently categorically.”

Circuit Judges Martin, Jordan, and Jill Pryor wrote their dissenting opinions. Even though they address a variety of issues with the majority opinion, they all have one thing in common: they all take issue with Florida’s current scheme. These judges foresee that this current decision will not be “viewed as kindly by history as the voting-rights decisions of [their] predecessors,” shared Chief Judge Pryor.

Circuit Judge Jordan does not believe that ballot access will be regained through the current methods put in place, while Circuit Judge Martin laments that he “cannot condone a system that is projected to take upwards of six years simply to tell citizens whether they are eligible to vote; that demands of those citizens information based on a legal fiction known as the every-dollar method; and which ultimately throws up its hands and denies citizens their ability to vote because the State can’t figure out the outstanding balance it is requiring those citizens to pay.”

Overall, in the 6-4 decision, the US Court of Appeals ruled to reverse the judgment of the district court and vacate the challenged parts of the permanent injunction.

Florida’s re-enfranchisement scheme is found by the Court to be constitutional and ex-felons must now pay all fines, fees, costs, and restitution before voting. Any changes to the process going forward rest in the hands of the citizens and legislators of the state of Florida.

To sign up for our new newsletter – Everyday Injustice – https://tinyurl.com/yyultcf9