By David M. Greenwald

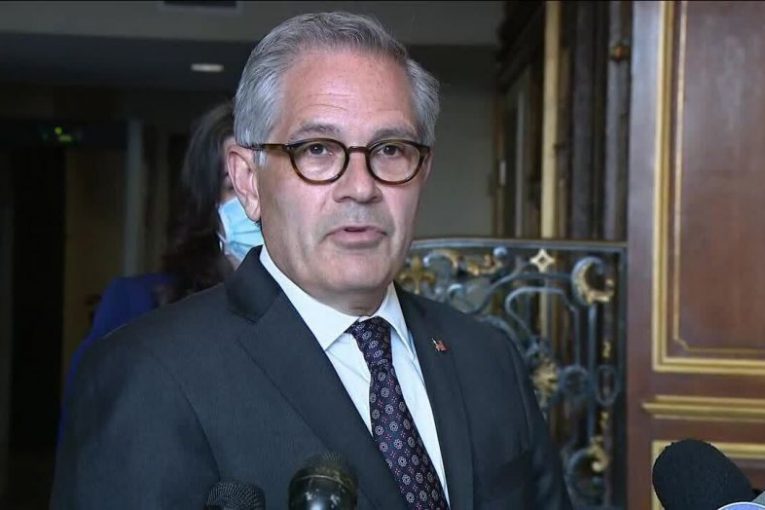

Philadelphia, PA – Long before there was George Gascón in Los Angeles and Chesa Boudin in San Francisco, the standard bearer for the progressive reform movement was Philadelphia DA Larry Krasner, who won a surprise victory in 2017.

Attempting to take him out was a state legislature who attempted to limit some of his powers and a Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) who fought him at every step.

He faced a well-financed and police-backed candidate in the primary on Tuesday and won overwhelmingly.

It wasn’t close. Most of the night, he was up by nearly a 2 to 1 margin over Carlos Vega, who finally conceded around midnight and the Associated Press called the race.

Given the overwhelming Democratic voter domination in Philadelphia, while Krasner faces a Republican, he is now all but assured victory in November.

“We in this movement for criminal justice reform just won a big one,” Krasner said in a victory speech. “Four years ago, we promised reform, and a focus on serious crime. People believed what were, at that point, ideas. Promises. And they voted us into office with a mandate. We kept those promises. They saw what we did. And they put us back in office because of what we’ve done.”

Make no mistake, this was an attempt by the police to take him down.

Vega himself was a former homicide prosecutor, and among 31 staffers that Krasner fired during his first week as DA.

He ran the campaign attacking Krasner as being soft on crime. The FOP supported his campaign with the largest expenditure from the police union in over a decade. They gave more than $100,000 to  Protect Our Police PAC, a political action committee that launched last year to push Krasner out of office.

Protect Our Police PAC, a political action committee that launched last year to push Krasner out of office.

The PAC then ran ads encouraging Republicans to switch their registration to vote in the Democratic Party. However, the PAC ran into trouble when it sent out a fundraising email blaming George Floyd for his own death. Still, the group spent $45,000 on TV ads attacking Krasner in the final month of the race.

Miriam Krinsky, who heads Fair and Just Prosecution, tweeted last night, “(Larry Krasner’s resounding win tonight is a sign that communities understand that failed tough on crime policies of the past don’t work—they want CHANGE.”

This was a huge victory for the progressive movement that in the last several years has seen victories all over the country. Last November, progressives won big victories in places like Ann Arbor, Michigan, Austin, Texas, New Orleans, Los Angeles and Portland. But more than that, they have now held onto important victories against serious assaults in St. Louis, Chicago and now Philadelphia.

As the AP put it, “Incumbent Philadelphia prosecutor Larry Krasner has won the Democratic primary. Pundits nationally saw the primary as the first test of whether a wave of prosecutors elected on criminal justice reform promises can survive a rising tide of gun violence.”

That has been a big question and it now will loom over San Francisco and Los Angeles—both saw victories by progressives in 2019 and 2020, both are now seeing pushback.

Larry Krasner, along with Kim Foxx in Chicago, in 2019, became a target for Donald Trump, who declared that prosecutors in Philadelphia and Chicago “have decided not prosecute many criminals” who pose a threat to public safety. Both have now won overwhelmingly.

This week, the Appeal released a poll by Data for Progress showing that a number of the reforms enacted by Krasner remain popular with voters.

Their polling found “75 percent of voters agreed that individuals who demonstrate good behavior and personal improvement should be eligible for sentence reductions.”

They also found that 64 percent support limitations on cash bail, 60 percent were in favor of the decriminalization of drug possession, and 68 percent supported terminating probation when supervision is no longer needed.

The result here figures to resonate loudly in California. George Gascón last November unseated incumbent Jackie Lacey. In March of 2020, he won just 28 percent of the vote (though he split a good amount of that with fellow reformer Rachael Rossi). By November he won by over 7.4 percent and over 200,000.

He ran on a platform of reform, but since then has been heavily opposed by the LA ADDA (deputy DA’s association) and law enforcement—a similar coalition to the one trying to take down Krasner in Philadelphia, which lost.

Meanwhile, Chesa Boudin eked out a narrow victory in November 2019 in San Francisco and faces a potential recall in San Francisco.

There have been some high profile incidents such as the parolee who ended up killing two people on New Years, and a number of anti-Asian hate crimes that have racked the city.

Opponents of both point out the overall rise in murders and shootings, though a more thorough analysis shows, in San Francisco for example, crime overall has fallen. And rises in murders seem to mirror a nationwide trend rather than resulting from any specific policies.

Polling in LA in February, from Data for Progress, again shows, just as was the case in Philly, strong support for reforms pushed by Gascón.

The polling “shows substantial support among Los Angeles County voters for a number of measures to reduce the jail population.

“Sixty-two percent of people favor releasing incarcerated people with less than 6 months left in their sentence,” the poll found. Moreover, voters do not want to see people detained pretrial unless necessary with more than 60 percent supporting “alternatives to jail” pretrial.

Tough-on-crime supporters may believe there is a backlash forming here, but looking at the results from Philadelphia and polling data from Los Angeles, they may be in for a surprise.

Scott Roberts, senior director of criminal justice campaigns at Color of Change told the Intercept that the agenda overall remains quite popular, despite the attacks and rise in some crimes.

“With all the noise that goes on, the attacks, what have you, we know that the agenda is still very popular,” said Roberts. “People want to see these prosecutors’ offices being focused on bringing down incarceration rates, and holding police accountable. And they’re actually looking for other solutions for violence, they’re not willing to buy into the narrative that they hear from police unions and conservative politicians.”

—David M. Greenwald reporting

To sign up for our new newsletter – Everyday Injustice – https://tinyurl.com/yyultcf9

Support our work – to become a sustaining at $5 – $10- $25 per month hit the link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crime_in_Philadelphia

That would not be a surprise given that it’s a large urban area, but what does that have to do with the DA’s race.

The only thing I know for sure is that if criminals are put into prison, they (personally) are no longer committing crimes outside of prison.

Unless they’re directing someone on the “outside” to do so.

So, that’s what it has to do with the DA’s race.

Of course, if a majority of residents don’t care about that, then they’ll elect someone who is less-aggressive about doing so. And, a given city may continue to lose those who “do” care, resulting in further decline.

The problem with your analysis is twofold.

First, if Philadelphia is “consistently” above the national average, that extends beyond the tenure of the current DA which meant that previous policies did not work.

But second, I think the focus on incarceration is wrongheaded.

“The only thing I know for sure is that if criminals are put into prison, they (personally) are no longer committing crimes outside of prison.”

But most don’t stay there forever. So one of the keys to reform is actually making it so that if they have to go to prison, they can be released and not commit new crimes and if we do it right, we can even better avoid prison time at all in a lot of cases. As I point out, we spent $85,000 on incarcerating one person for one year. That’s about the same as a year of Harvard education. That means we can and should reinvest that money into things like education, job training, mental health services – do a better job of keeping people from committing crimes and using resources better.

You have previously (and accurately) pointed out that most people “age-out” of crime. In any case, I’d suggest not releasing those who have committed serious crimes until they are no longer deemed a probable threat.

Personally, I think that criminals have the primary responsibility to “do it right” – as most other citizens (already) do. They’ve already demonstrated a propensity to “do it wrong” in the first place.

I question that figure, regarding incarceration. But one thing I’d suggest is a much-improved incentive system, which encourages prisoners to help offset their costs, while also benefiting them personally (via work programs). Perhaps also gaining greater privileges while incarcerated, along the way.

I’d also suggest that prisons themselves explore ways to ensure a much-greater degree of personal safety (between inmates), while incarcerated.

There’s a reason that they’re called “correctional facilities”.

And of course, that “Harvard education” does not include the “room-and-board” that prisoners receive.

Would you suggest putting them up at perhaps a place like Sterling apartments, while they attend universities for free? If so, perhaps an entire generation of college students will commit crimes – just to get that benefit which is denied to them. 🙂

Found this interesting:

Think about it – it has a lot of truth to it. Because the thing is, murders are up everywhere not just in cities with Krasner or Boudin. Also places like Oakland where O’Malley is a traditional DA.

Gee, what a “strong endorsement” for the criminal justice reformers: “It’s bad, everywhere”.

Did the point just fly completely over your head? You can’t explain variance by using a constant. Meaning if crime went up everywhere, pinning it on a local policy doesn’t make empirical sense.

If the point is to reduce crime, then the change in policy from the reformers isn’t exactly a “ringing endorsement”.

I suspect that recidivism rates (e.g., of those not fully prosecuted, or released early) would be the best measure. Might take some time to see the overall results.

And if there’s no other significant changes to discourage recidivism, it seems extremely likely to go up.

Folks in prison usually find it challenging to commit crimes outside of prison, without recruiting someone on the outside.

Think about this: what is the biggest change in the world between 2019 and 2020-21? By far the pandemic. So isn’t that going to override a lot of other things?

Let’s use a different example to illustrate the problem.

Half the states passed new laws prohibiting the use of alcohol. Crime rose. Crime rises about the same rate for those who allow alcohol still as those who prohibited it. Can you infer from that data whether crime rising was caused by changes in the alcohol laws? No.

But wait, you say, banning alcohol was supposed to reduce crime. And it didn’t. But because the crime rose uniformly, you cannot make a judgment based on the data.

That’s what is happening here. And in fact, while you focus on one side of the equation, you ignore the fact that tough on crime locales also had violent crime rise. So by your argument, that’s not exactly a “ringing endorsement”

Unless of course, you are reading noise rather than a signal. In which case, you are reacting to surface data rather than adequately analyzing it – over time and not during extraordinary circumstances.

So you’re saying we’ve been living in prohibition times against murder and robbery?