By David M. Greenwald

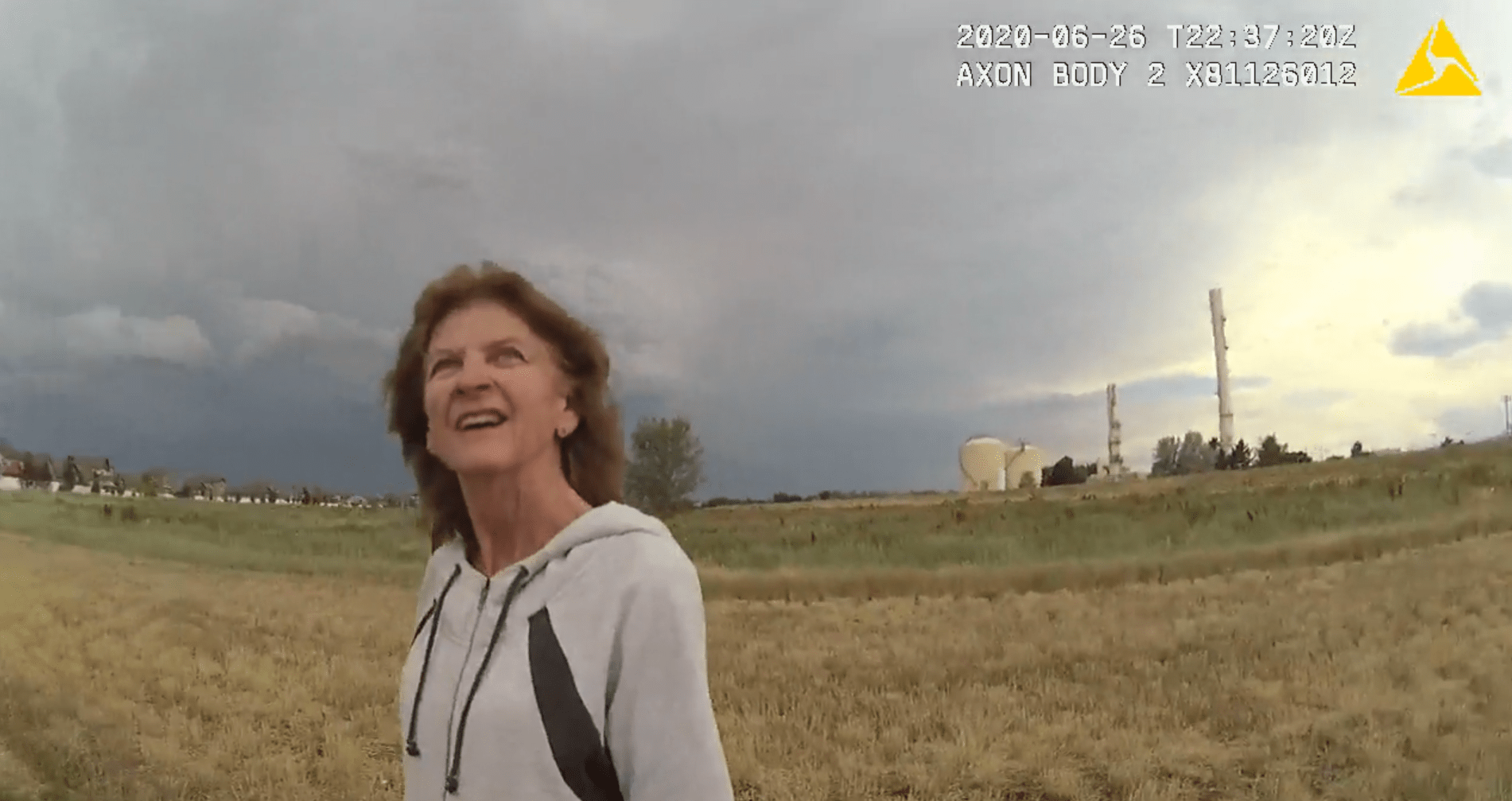

Earlier this week we covered the story of a 73-year-old woman with dementia who was taken to the ground violently by an officer in Colorado, mistreated, and the officers got caught on video cracking jokes about it afterward.

The incident happened last year, but when her family filed lawsuit, her attorney released the video this month and the outrage led to all of the officers involved resigning this week.

For me, this incident better illustrates the problem of policing than the George Floyd situations. As bad as Floyd was with its potential to be a transformative event, officer-involved killings amount to only around 1000 a year—a number that is far more than most places on the planet and far too high. But that number allows defenders of the police to claim this as a rare event and to claim Derek Chauvin as simply a bad apple.

When you put the Karen Garner as opposed to the Eric Garner situation into perspective, it’s harder to explain away.

The first problem is that, without the lawsuit, we wouldn’t know about this case. That means that the problem does not simply stop with the two sworn and one community resource officer who resigned, but everyone in the chain of command who knew about this and said nothing and did nothing until this became public.

Second, the base incident was very minor. She took $13 worth of merchandise.

Third, the officer used force—within eight seconds, apparently, of encountering her even though at 73 years old and 80 pounds and no weapon, she couldn’t possibly been a threat to the officer.

Fourth, the officer never conducted a welfare check, never recognized clear symptoms of dementia, never brought in medical attention.

Finally, the officer acted in a callous and demeaning fashion, which is likely the reason for the outrage in this situation and why he was forced to resign, but the other problems are just as troubling and, from what I have watched over the last 10 to 15 years, frighteningly common.

These situations are the reason why there is such a call for reimagining policing. They scream for a different approach with a trained mental health professional, rather than a clearly untrained person with a gun who only knows one approach to an uncooperative patient.

As it turned out she not only suffers dementia, but also a form of aphasia that makes it difficult to cooperate with her. At one point early in the encounter one of the officers asked if she had been drinking, while the other officer had no idea what he was dealing with—somehow he never guessed that she might have dementia? It’s inexcusable.

Unlike what you are told by police officials and other defenders of policing, these are not rare occurrences. The data from this survey is from 2005, but there is no reason to believe anything has changed.

According to a Justice Department survey, 19 percent of all adults had direct face-to-face contact with police in 2005—of those surveyed roughly 1.6 percent report the use of force or the threat of the use of force.

That rate is more than double for Blacks at 4.4 percent and 2.3 percent for Hispanics than the 1.2 percent for whites.

That doesn’t sound like a lot but that comes to, over a year, nearly one million people or 991,930 estimated to have experienced some level of force including threats, with 546,000 subject to physical force.

That’s just one year, and, if anything, that number is higher now as we have seen the number of officer-involved killings go up.

Are some of these uses of force legitimate? Of course. But we also know that in a given year, over 1000 people are killed by police, whereas the number of police murdered on the job is less than 50.

The same source found that in 2005, there were 57,546 officers assaulted in their course of work with most involving unarmed assailants (80 percent) and resulting in no injuries (77 percent).

While not minimizing that, the numbers show that officers are about 10 more likely to use force rather than be assaulted.

And, of course, use of force does not end the story earlier here. We have focused heavily on racial profiling or pretext stops. Studies continually show that people of color are far more likely to be pulled over, removed from their vehicle and searched than white people.

Kristian Williams in her 2014 edition of Police and Power in America points out that the data show that profiling does not work and “race is useless as an indicator of criminality.” Citing a study from the New Jersey Turnpike, they found “While Blacks and Latinos accounted for 78 percent of those search at the south end of the New Jersey turnpike… evidence was more reliably found by searching White people: 25 percent of White people searched had contraband, as compared to 13 percent of Black people and 5 percent of Latinos.”

What that tells us is that when searching Black and Brown people cops are using race as a proxy for suspicion, whereas when searching white people, they are looking for actual evidence.

A key problem with profiling, as Williams points out, is a logical fallacy of inferring an individual’s behavior from group tendencies. Social scientists call this an ecological fallacy—inferring individual level behavior from group data.

Williams writes, “An individual’s ability to rent, to perform a job, or to obey the law, cannot be judged on the basis of the statistical performance of a group to which she belongs.”

Aside from the frequent occurrence factor, there is also the escalation situation.

As the Marshall Project points out, “Before Derek Chauvin was convicted of murdering George Floyd, he was the subject of at least 22 complaints or internal investigations during his more than 19 years at the department, only one of which resulted in discipline.”

That means that by failing to deal with complaints and uses of force, eventually some of these officers are going to end up killing someone. That death may have been preventable with a more proactive approach by the department. None of that is possible unless we take seriously lower level offenses than officer-involved killings.

My point here is to demonstrate that, while officer-involved killings —over 1000 a year, between two and three each day—are comparatively rare events, by focusing on them rather than profiling, police stops and use of force, we are underestimating the problem of policing by a large margin. About 1400 people each day have an officer use physical force on them. Half a million a year. Every year. It’s a huge number. Even if you want to argue that improper use of force is a small number, how much of it is actually necessary to keep ourselves and the officers safe?

The problem is, we don’t have the answer to that. But we need to.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

To sign up for our new newsletter – Everyday Injustice – https://tinyurl.com/yyultcf9

Support our work – to become a sustaining at $5 – $10- $25 per month hit the link:

3078 he says sarcastically

Of course the answer is some of it, not all of it.

I agree with most all you say in this article – but why this headline for this article?

No, just like your question about lesser-than-shootings — which is a good point — not all officer-involved shootings are bad — but some of them are. Headlines like that don’t help. The idea is to reach what you call ‘defenders of the police’, not alienate them. I both agree with your essay, and am also a defender of the police – to the extent of as is necessary relative to statements such as ‘police killings are bad’, which implies all police shootings are unjustified — which just isn’t true. In other words, while bringing up good points, you are making the divide worse by putting people into camps instead of seeking the common ground. By you I mean both you and the movement.

Which brings me back to a response a few weeks ago where you acknowledged I had a point, but never addressed one of my points which was — why were you posting a picture from the Central Park ‘art’ installation which had a prominently displayed “Abolish the Cops / Abolish Prisons” poster. Is that because that is truly how you swing?

I had criticized the earlier phrase, “Defund the Police” as harmful (as have many national writers) to the movement, because it is so widely defined, and because those that don’t hear the dog whistle hear “dismantle” or “completely defund” the police. So then this is ‘explained’ away as “WE” actually mean ‘take away some of the funding and put it into social services’. OK, I’ll consider that . . . BUT THEN . . . . . . !!! . . . . . .

I go to the newspaper and am reading about a protest in Sacramento last week — and the march is defined as . . . just like the poster in Central Park . . . an “Abolish the Police” march. Are you going to explain that one away, too? Is this abolish movement some new thing? I think abolish is pretty cut & dry. So really, there was no explaining away of ‘defund the police’ — in truth ABOLISH has really been the intent of many all along it would seem.

So, DG, are you willing to distance yourself from, even condemn, the “Abolish the Police” movement, so that those things you call for in this article, which are reasonable, could actually be shared with, and brought into play with, a wider audience?

Or are you going to be like Donald Trump, and embrace the radical fringes of your “side” for political reasons, for fear of alienating the extremists, and therefore, much of your base readership?

I don’t agree with the Abolish the Police movement in the sense that I don’t believe we can function without police. However, I might argue that we should completely change what police are asked to do, how we train them, their required expertise, use of force rules, etc. Unfortunately I believe that a much larger proportion of cops act like the guys in Colorado than most people are willing to acknowledge.

Bottom line: we need police, what that looks like I would like to drastically change however.

One of the most famous (infamous?) quotes… “My Country (or police, or whatever), right or wrong!”

The most appropriate, it seems was one:

The sentiment of Mr Schurz, I support, and urge others to think similarly… might lead to constructive actions…