By Christopher Bryson

CRITICAL RACE THEORY is an academic tool generally taught in graduate school curricula. It addresses inequities within society, which has led to its being thrust into the national spotlight. In order to reduce the long-standing gaps in achievement among our nation’s students, equity initiatives have been introduced — and are creating significant controversy. Bills seeking to prohibit the teaching of sexist, racist, or divisive concepts in schools are being instituted in numerous states. Republican legislators cite critical race theory as an impetus behind such measures, and bans of the theory have been signed into law in Idaho, Iowa, Texas, Oklahoma, and Tennessee.

According to research by Media Matters, during the past several months 1,300 stories warning of the inherent dangers of teaching critical race theory in public schools have been broadcast on Fox News alone. The phrase “critical race theory” has found its way into over 340,000 posts on Facebook public pages and groups, with the phrases “CRT” and “school board” generating nearly 70 million interactions.

The coverage of critical race theory in the national media juxtaposed with the political agenda of conservatives and activists has increased tension in schools regarding the subject. Some have even proposed equipping teachers with body cameras to monitor whether the subject is being  taught.

taught.

The theory is a framework to build a more comprehensive understanding of systemic problems that perpetuate racial disparities. It does this by attempting to contextualize the effects of rules and laws put into place during a time in America when ideas considered racist today were in fact protected by law and deemed culturally acceptable. This history has resulted in generations of social disadvantages and systemic inequalities. In the 1960s, post-Civil War racism was addressed by the Johnson administration’s civil rights legislation, with extensive pushback. No measures were ever put in place in order to compensate for the historical disadvantages of an entire race of people. Racism, in many ways, was still culturally acceptable. It has taken another 60 years to reach the point where the theory of critical racism has become the socially engaged topic it is today.

Recent social justice movements and activist protests around the country — and the world — signal that conscious racism is, if not fading, at least acknowledged as a valid social issue. The question then becomes: Why does systemic racism still exist? Perhaps the gaps in socio-economic status and education play a part, and critical race theory helps identify the effects of policies derived from a time in history when racist intent was overt in this country. The theory examines if and how racism has influenced American law and institutions.

Some see no benefit to the theory and training in equity and diversity. Opponents of its application fear that critical race theory will be used as a weapon to confront and accuse individuals of racism if they disagree with its conclusions.

When asked their opinion about critical race theory being taught in schools, Mule Creek State Prison correctional officers A. Thornton and S. Hpoo said they believe that parents should be responsible for informing their own children about the subject of race and racism. “It all starts at home,” Hpoo said. “We all should be teaching our own kids this stuff.” Thornton agreed. “Those are values that you learn at home. It should not be taught in schools.” Both officers undergo annual diversity training as a requirement of employment within the Department of Corrections. Literacy instructor C. Taylor spoke from his experience as a life-long educator: “I think the CRT debate is really a debate about equality of outcome versus equality of opportunity. It seems as though it is being used to separate instead of bringing people closer together.”

Perhaps disparities and difficulties faced as a result of racial inequity force the conversation. It is not always easy or comfortable addressing topics so steeped in controversy. Humans can become comfortable in the routine of how things are and how things have been done in the past. When we face these difficult topics and engage despite differing opinions, the dialogue can be a productive step in the right direction.

(Sources:VisliaTimesDelta.com, July 7, 2021; TulareAdvanceRegister.com, July 7, 2021)

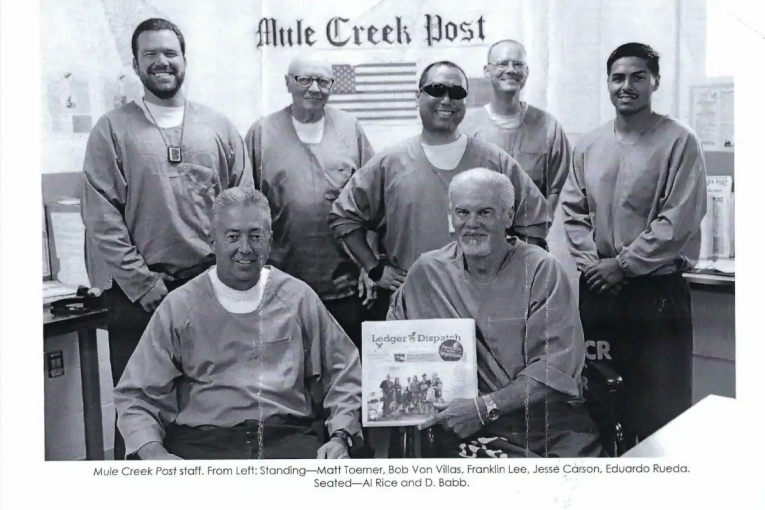

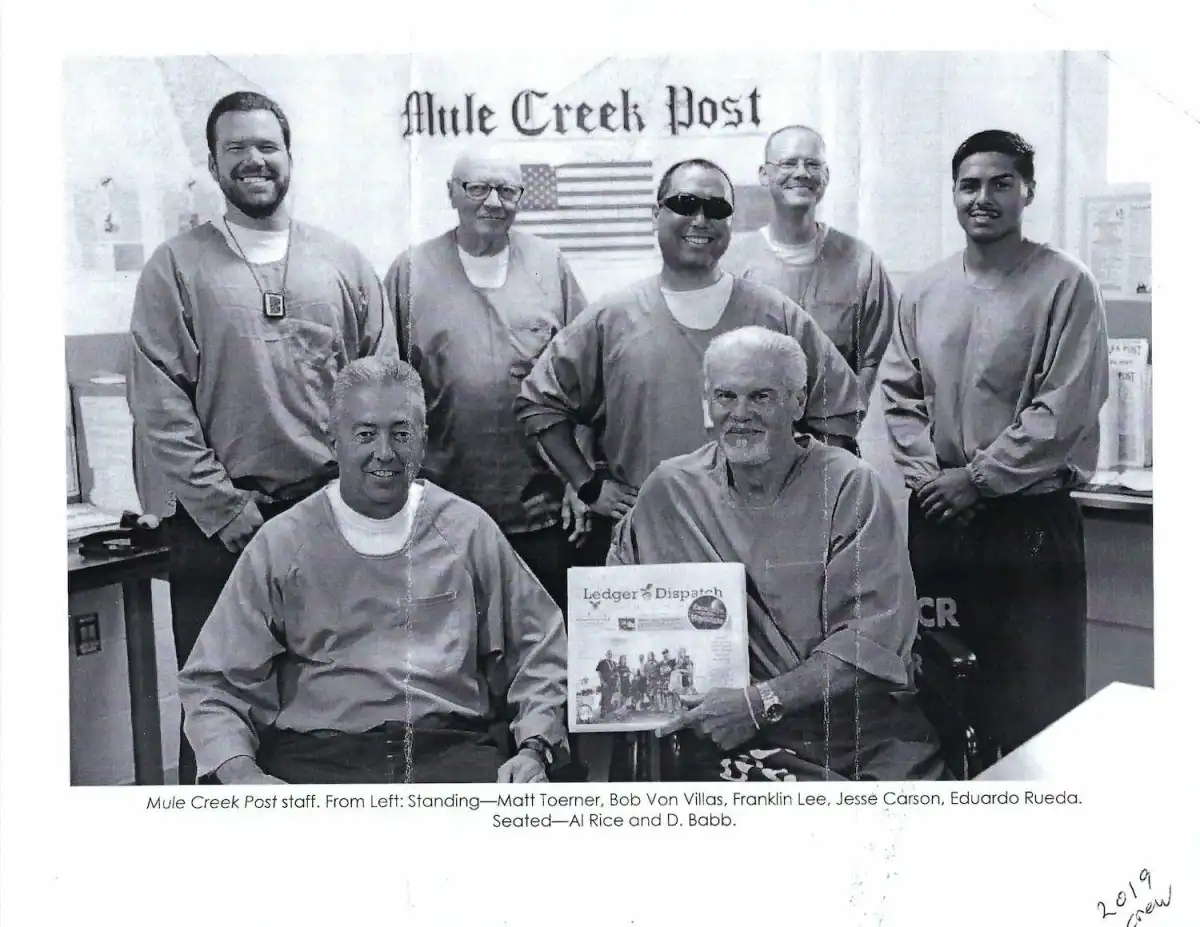

Originally Published in the Mule Creek Post