By Rory Fleming

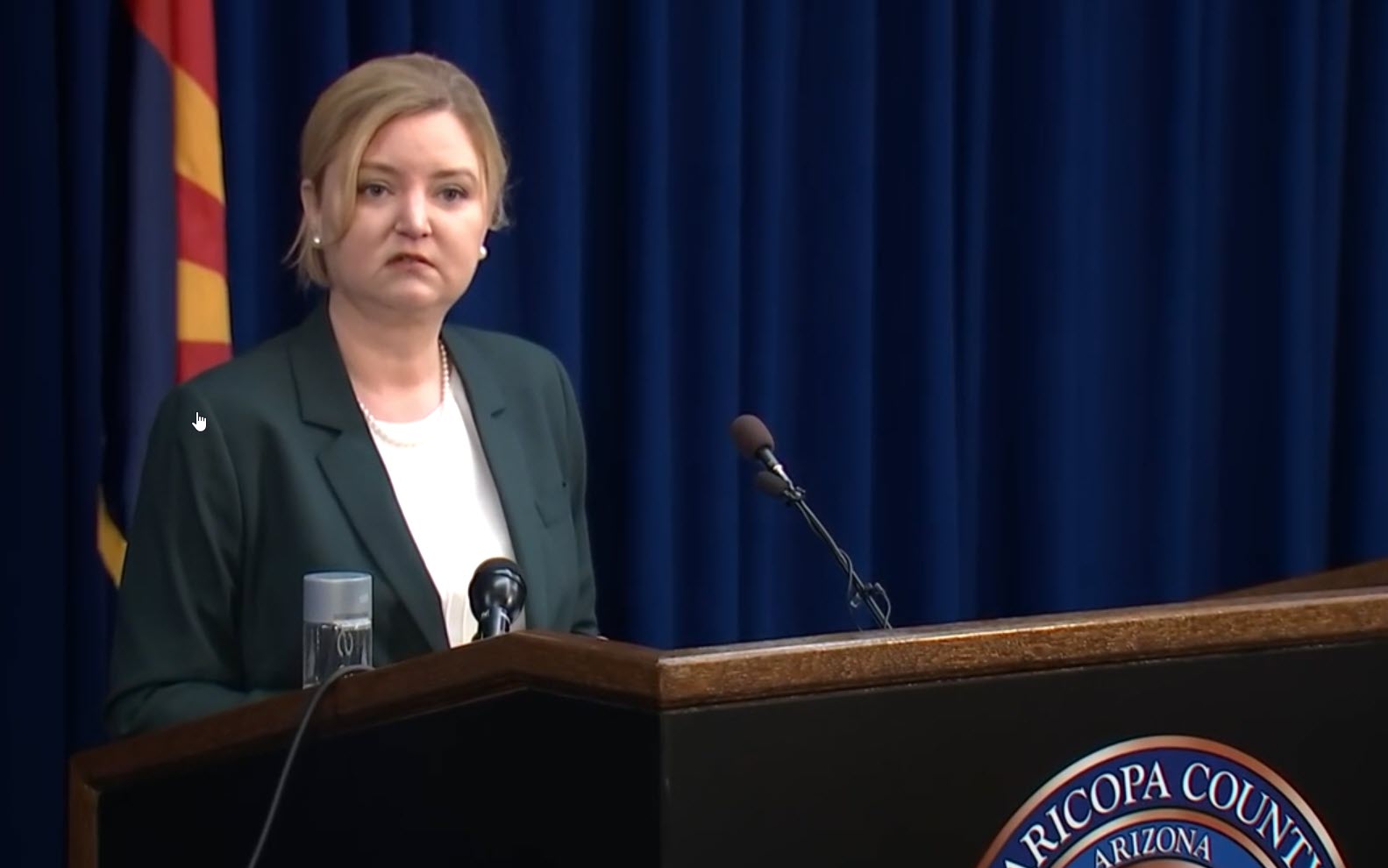

Too often when prosecutors are called out for unethical or irresponsible behavior, their response is to become histrionic and hysterical. That is exactly what Maricopa County (Phoenix) Attorney Allister Adel has done, as evidenced by a letter signed by the Phoenix-based elected prosecutor and obtained by ABC15 reporter Dave Biscobing.

Let us set the stage. Adel runs the prosecutor’s office in the fourth largest county by population in America, serving roughly 4.5 million residents. That is like being the attorney general of Oregon or Louisiana, states that have roughly the same number of people.

Adel’s tenure has been wracked with controversy: not because she is too decarceral for some constituents’ tastes, like many urban top prosecutors today, but because of allegations that her substance use disorder has rendered her incompetent. Adel claims that repeated stays at out-of-state rehab facilities, including one in California, do not impact her ability to serve as office chief, especially due to the common nature of remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Problematic patterns of illicit substance use are endemic in the legal profession. About 20 percent of lawyers undertake “hazardous, harmful, and potentially alcohol-dependent drinking,” according to a 2016 study published by the Journal of Addiction Medicine.

But, beyond personal quality-of-life concerns, heavy drug or alcohol use only really becomes an issue for attorneys under two circumstances. When a lawyer is arrested or charged with a crime, even simple drug possession, he or she has a duty to report to the state bar for potential discipline.

Also, lawyers have a duty to deliver competent representation to their clients, whether that be defendants or the state. When substance use or mental health issues are interfering with a lawyer’s ability to practice law, the safest bet for that lawyer is to voluntarily suspend his or her license.

Private attorneys appear somewhat more willing to admit they have a dehabilitating problem than elected prosecutors. In Dallas, Texas, former DA Susan Hawk spent much of her year-and-a-half tenure in drug treatment mental health facilities before finally admitting to herself she could not presently handle the job. (Her repeated stays at facilities, including one in Arizona, are what sparked calls for resignation.) In Austin, former DA Rosemary Lehmberg initially refused to resign after a nationally-publicized DUI arrest.

Just like in many criminal cases any prosecutor’s office brings, no one can say with 100 percent certainty that Adel drinks alcohol on the job. But many, including her own division chiefs of the Trial Division and the Juvenile Division, attest to this and other problems. They sent a letter asking Adel to resign and copied the state bar and the county board of supervisors.

That is not a step to be taken lightly. The potential for retaliatory action from Adel is immense, though she does not state in her letter in response to these staffers that she plans to fire them. Instead, she berates them for being unprofessional while trying to argue she is doing a good job. There is also a hint of anger about being treated differently because her health condition is addiction-related rather than any other disease.

The ongoing drama about Adel’s performance helps prove her disgruntled middle management’s case. How much in the way of tax dollars is being spent on members of this massively impactful office fighting out their differences behind closed doors?

Importantly, there is no way this is a matter of these staffers wanting to remove Adel because she is too liberal or conservative for their tastes. These managers are hold-overs from Bill Montgomery’s tenure. Adel speaks in a friendlier fashion when it comes to the low-hanging fruit of criminal justice reform, such as expanding diversion for drug offenses, but both she and Montgomery take a tough-on-crime conservative approach to the job overall.

Adel says that if someone is going to make her resign, it will be the voters. That is just another way to say that voters deserve what they get when they make bad choices.

Rory Fleming is a writer and a lawyer