Posted by Matt Williams

Caltrans Planning Horizons: Induced Vehicle Travel in the Environmental Review Process

Empirical research shows that expanded roadway capacity attracts more vehicles. However, environmental impact assessments of roadway expansion projects often ignore, underestimate, or mis-estimate this induced travel effect and overestimate potential congestion relief benefits. A very recent ITS-Davis presentation on September 29, 2021 covered an online tool developed by UC Davis to facilitate estimation of induced vehicle travel impacts of roadway capacity expansion projects. For more information email kevin.k.chen@dot.ca.gov.

Increasing Highway Capacity Unlikely to Relieve Traffic Congestion

ITS-Davis reports that reducing traffic congestion is often proposed as a solution for improving fuel efficiency and reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Traffic congestion has traditionally been addressed by adding additional roadway capacity via constructing entirely new roadways, adding additional lanes to existing roadways, or  upgrading existing highways to controlled-access freeways. According to ITS-Davis numerous studies have examined the effectiveness of this approach and consistently show that adding capacity to roadways fails to alleviate congestion for long because it actually increases vehicle miles traveled (VMT).

upgrading existing highways to controlled-access freeways. According to ITS-Davis numerous studies have examined the effectiveness of this approach and consistently show that adding capacity to roadways fails to alleviate congestion for long because it actually increases vehicle miles traveled (VMT).

An increase in VMT attributable to increases in roadway capacity where congestion is present is called “induced travel”. The basic economic principles of supply and demand explain this phenomenon: adding capacity decreases travel time, in effect lowering the “price” of driving; and when prices go down, the quantity of driving goes up. Induced travel counteracts the effectiveness of capacity expansion as a strategy for alleviating traffic congestion and offsets in part or in whole reductions in GHG emissions that would result from reduced congestion.

Environmental Reviews Fail to Accurately Analyze Induced Vehicle Travel from Highway Expansion Projects

ITS-Davis reports that induced travel is a well-documented effect in which expanding highway capacity […] induces more driving. This increase in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) increases congestion (often back to pre-expansion levels) and air pollutant emissions, reducing or eliminating the purported benefits of the expansion. Yet highway expansion projects continue to be proposed across California, often using congestion relief—and sometimes greenhouse gas reductions—as a justification for adding lanes. These rosy projections about the benefits of highway expansion projects indicate that the induced travel effect is often not fully accounted for in travel demand models or in the projects’ environmental review process.

With this problem in mind, researchers at the University of California, Davis developed an online tool to help agencies estimate the VMT induced annually by adding lanes to major roadways in California’s urbanized counties. The researchers also applied the calculator to estimate the vehicle travel induced by five highway expansion projects in California that had gone through environmental review within the past 12 years. They then compared their estimates with the induced travel analysis completed for the projects’ actual environmental impact assessments. This policy brief summarizes findings from that research, along with policy implications.

Take it from Caltrans: If you build highways, drivers will come.

The analysis found that adding a lane in each direction border-to-border will save I-95 travelers well over 14 million hours of delays by the year 2040. Likewise, the widening of I-84 will save travelers over 4.7 million hours of delays during the same period.

Bloomberg goes on to report that congestion relief itself is a dubious claim when it comes to road expansions. Transportation experts have repeatedly found that building new roads inevitably encourages more people to drive, which in turn negates any congestion savings—a phenomenon known as “induced demand.”

So it’s refreshing — and rare Bloomberg goes on to say — that CalTrans by way of a link to a policy brief outlines important research findings from years of study into induced demand. The brief, titled “Increasing Highway Capacity Unlikely to Relieve Traffic Congestion,” compiled by UC-Davis scholar Susan Handy found that:

- There’s high-quality evidence for induced demand.

- More roads means more traffic in both the short- and long-term.

- Much of the traffic is brand new. From leisure trips that drivers aren’t willing to make in bad traffic.

Bloomberg noted that the 2014 assessment of Caltrans, conducted by the State Smart Transportation Initiative (SSTI), specifically cited induced demand as a research finding that had yet to filter down “into the department’s thinking and decision making”:

For example, despite a rich literature on induced demand, internal interviewees frequently dismissed the phenomenon.

Ronald Milam of the transportation consultancy Fehr & Peers told Bloomberg that CalTrans has recognized the shortcomings of traditional traffic models and tried to improve its analyses to better account for induced demand. State of Connecticut officials also seem to understand that expanding roads won’t resolve the state’s traffic problems. “You can’t build your way out of congestion,” Tom Maziarz, chief of planning at the state DOT, recently told the Connecticut Post. And yet the interstate widening project moves forward.

Induced Demand — When traffic-clogged highways are expanded, new drivers quickly materialize to fill them. What gives? Here’s how “induced demand” works.

Bloomberg News reports that with 26 lanes at its widest point, the Katy Freeway in the Houston metro which made it at that time the widest freeway in North America, was the result of an expansion project that took place between 2008 and 2011 at a cost of $2.8 billion. The primary reason for this mega-project was to alleviate severe traffic congestion.

Unfortunately, after the freeway was widened, congestion got worse. Data from Houston’s official traffic monitoring agency found that travel times increased by 30 percent during the morning commute and 55 percent during the evening commute between 2011 and 2014. Bloomberg reports that as a textbook example of induced demand, which refers to the idea that increasing roadway capacity encourages more people to drive, thus failing to improve congestion.

Summary

Nearly all freeway expansions and new highways are sold to the public as a means of reducing traffic congestion. It’s a logical enough proposition, one that certainly makes plenty of sense to anyone who’s stuck in traffic: Small communities served by small roads grow bigger, and their highways need to grow with them. More lanes creates more capacity, meaning cars should be able to pass through faster. But that’s not what always happens once these projects are completed.

In situations of induced demand means the new roadway capacity creates new demand for those lanes or roads, maintaining a similar rate of congestion, if not worsening it. The principle is simple economics … when you provide more of something, or provide it for a cheaper price, people are more likely to use it.

Transportation researchers have been observing induced demand since at least the 1960s, when the economist Anthony Downs coined his Law of Peak Hour Traffic Congestion, which states that “on urban commuter expressways, peak-hour traffic congestion rises to meet maximum capacity.”

Bloomberg reports that there has also been a de-facto stance of most public officials and departments of transportation in the United States and much of the world, which have largely avoided reckoning with induced demand in their long-term planning. But the public and their elected representatives could be starting to see the writing on the sound barriers. Many departments of transportation are instead touting the benefits of toll lanes, a more au courant form of roadway capacity expansion.

How It Works

Induced demand is often used as a catch-all term for a variety of interconnected effects that cause new roads to quickly fill up to capacity. In rapidly growing areas where roads were not designed for the current population, there may be a great deal of latent demand for new road capacity, which causes a flood of new drivers to immediately take to the freeway once the new lanes are open, quickly clogging them up again. In aggregate, these choices put more cars than ever before on the newly expanded road, increasing net vehicle miles traveled (VMT) (and greenhouse gas emissions).

In the longer term, roadway expansions make an impact. Businesses that rely on trucking are more likely to locate near these new roads. With those new jobs, and access to countless more via the higher capacity road, housing developments and shopping centers spring up nearby. Urban form responds to existing infrastructure: Roadway capacity expansions spawn autocentric development patterns that utilize the new roads.

How quickly does new road capacity get filled up?

Bloomberg reports that it is important to note that measuring induced demand is a somewhat inexact science. Most studies provide ranges that estimate the amount of road capacity that is filled by induced demand over a given period of time. One literature review, conducted by Susan Handy of UC Davis for CalTrans found that a 10 percent increase in road capacity yields a 3 to 6 percent increase in vehicle miles travelled in the short term and 6 to 10 percent in the long term.

The DiSC proponents apparently disagree with this finding.

Of course, they also claim that there is no increase in greenhouse gasses as a result.

And yet, they’re suing opponents for false claims – led by Dan “DiSC will Save the World” Carson.

Matt, thanks for making the point, if difficult to distill the point is made. What then is perplexing is why is Caltrans still pushing for the I-80 managed lanes project, as surely those lanes will induce demand; AND, why does the ITS Davis continue it’s long-time policy of promoting electric cars — which are only as clean as the grid, do nothing to reduce sprawl and sprawl planning, have no healthy/active component, and don’t solve traffic or the need for infinite highway expansive one iota? Why?

Alan, I believe the level of your knowledge of transportation facts and history makes your personal distillation of the point a bit more complex than it is for most folks … you are going much deeper into the issues than the vast majority of readers would go. The questions you ask are very consistent with that deeper thinking. I would love to sit down with you over some form of liquid refreshment and discuss those questions.

With that said, for most Davis readers I believe the point is much simpler. That point is that any hope that the planned expansion of I-80 will provide a relief valve for any of the feeder streets is a hope in vain. The ability of I-80 to accept a higher volume of vehicles at the entrance ramp merger points will only exist if there is “spare” capacity on I-80 to accept the incoming/merging vehicles without any meaningful slowing down of the thru traffic on I-80 … and the studies clearly show us that no such “spare” capacity will exist for any meaningful amount of time.

Right now, because of the congestion, every entering/merging vehicle causes disruption/turbulence in the thru traffic flow traveling along those three I-80 lanes. Disruption/turbulence causes drivers on the Interstate to perceive higher levels of risk … and slow their vehicle’s speed in order to mitigate that risk. They also increase the amount of distance between their vehicle and the vehicle in front of them, so if they have to take evasive action, they have more leeway to do so. All that causes CalTrans to heavily restrict (with their meter lights on the ramps) the number of vehicles that enter the Interstate from the entrance ramps.

What the induced demand data says is that the added fourth lane will quickly be filled with additional traffic, such that there will almost immediately be no “spare” capacity.

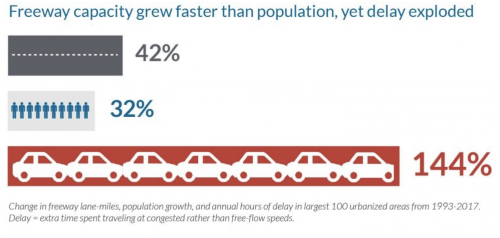

The ramp meters will continue to cycle every 13-15 seconds (7 to 8 vehicles a minute … 420 to 500 vehicles an hour) and the current level of backed-up traffic on Mace will not reduce. Further, every one of the vehicles that is part of the projected 12,000 additional vehicle trips a day will increase the existing delay. The graphic in the article isn’t specific to Mace or I-80, but it clearly shows that a 42% increase in lane miles (the CalTrans proposal for I-80 will be a 33% increase from 3 to 4 lanes) has historically produced a 144% increase in traffic delay.

To put that delay increase into human terms a 144% increase in a 10 minute congestion delay would increase the 10 minutes to 24.4 minutes. A current delay of 20 minutes would increase to a 48.8 minute delay. And a current delay of 30 minutes would increase to 73.2 minutes.

Each of us can think about our historical experience with delays on Mace and do the calculation. I know I have timed one of my trips that gave me a 25 minute travel time from Harper Junior High School to the Mace-Chiles intersection. A 144% increase in that would increase the delay to just over an hour.

And the Mace Blvd. congestion south of I-80 is a microcosm for how induced demand works on existing roadways due to social media apps. Waze and others effectively created new capacity when drivers are routed off I-80 to Tremont Road at the Pedrick Road exit. This section of Mace Blvd. was a road that was underutilized prior to Waze and others because it was serving a small local population and it had really more lanes than needed. Once Waze identified it as an underutilized alternative route, the induced demand was immediately met. It also happened to coincide with the traffic calming improvements funded by SACOG and the reduction of a lane in either direction was blamed for the congestion. None of the outspoken critics of the Mace Blvd reconfiguration will ever recognize the real source of congestion or that the only real solution is to make the entire Tremont corridor slower and more turbulent so that the Waze algorithm recognizes Tremont/Mace as a poor alternative.

Makes me wonder if the best solution is not to gate Tremont off near the Cemex concrete plant or to the east of Lowrie Trucking and provide an on-demand gate opener for local farm or industrial users. All the sudden you’ve added several minutes to that I-80 alternative. A lot cheaper than traffic lights and does not require constant law enforcement. It’s Solano County, so there is that to consider, but I wonder if this idea was ever considered.

You seem to be saying this is a good thing? If so, I wanted to point out a) roads so ‘underutilized’ that became WANE-induced routes do not have the safety features for a massive influx of traffic. Longer term, these county roads are being beat to héll with state regional traffic traffic and will require rebuilding much sooner than previous maintenance cycles allow. Thus, this should be an issue the state deals with or fixes with legislation.

Again this is such a massive problem all over that it needs a global fix, not a series of local expensive solutions to a software-induced problem.

I’d ask SACOG what to do about these issues, and how to resolve them. They seem to have some good ideas, and funding to implement them.

Or, might want to ask Mr. Wiener, directly.

I am not saying underutilized capacity is a good or bad thing although one could argue Mace Blvd was overbuilt for the need at the time. We must remember that in the late 1960s when El Macero was conceived gasoline was about $.70/gal and driving cars was nothing but the best of all possible worlds. So building a luxury housing development miles from the nearest store surrounding a golf course in the middle of the country was the ultimate American dream scene. That section of Mace Blvd was never busy even with the city of Davis beginning to encroach and surround this rural paradise. Around 2010 with the advent of traffic routing apps on cell phones, it was “discovered” as a link to I-80 and a time saver. The city’s reconfiguration ideas began sometime around 2012 before the WAZE craze got so big. By the time SACOG awarded the grant to get the work designed and completed the WAZE craze had really messed up Mace Blvd fed by Tremont Road. It was a situation just waiting for the modern world. And, yes, I will admit that gating off a road here or there is the wrong approach. I was brain-storming on the Vanguard. If we plugged it up there, it would burst out somewhere else.

The question is, will the city’s proposed “fixes” to a social problem bear enough fruit to justify the $4Million they have decided it will cost to implement a plan that may only mitigate the problem partially. Or, maybe a partial mitigation is the best solution so as not to spread the problems elsewhere.

“Right of way” (roadway width) has a different ‘planning horizon’ than ‘current need’… by 50-100-200 years…

You don’t need to build out the roadway to the right-of-way, right away, except if you don’t, you risk big-time push-back later… no easy solution to that…

Basics…

I officially rename the “Mace Mess” the “Mace Waze Craze”.

I like “Mace Mess” better.

Interesting contrarian viewpoint here from Reason:

https://reason.org/commentary/examining-the-induced-demand-arguments-used-to-discourage-freeway-expansion/

Excerpts:

Tell that to all of the new development in the region (e.g., Natomas, Elk Grove, Roseville, Folsom, etc.). How many cars per household (and in total) do you think that adds?

As I understand it, “induced demand” only deals with existing levels of population and development (and resulting increases in traffic as a result of adding new capacity) – let alone the impacts of new developments.

Honestly – regardless of the obvious impact of DiSC, does anyone really believe that adding a Lexus Lane on I-80 will offset the traffic impacts of all of the new development in the region? I don’t think that even the most ardent DiSC supporters actually believe that.

Don, thanks for sharing that info. I read it less as contrarian, and more as moderated. It is always important to keep data current.