By David M. Greenwald

Executive Editor

Davis, CA – The city of Davis has contracted with Cascadia Partners to complete a study of rental inclusionary housing requirements.

Staff notes, “The City has contracted with Cascadia Partners to review multifamily developments to understand the feasibility of different inclusionary housing policies for rental housing projects, with the ultimate goal to recommend an updated inclusionary housing ordinance for the City.”

When Cascadia presented their initial findings to the Social Services Commission in September, the Commission passed a motion that included a recommendation for the City Council to explore additional options to incentivize non-profit and public housing development.

The city has for the last several years been passing a series of temporary ordinances that established “an alternative affordable housing target of 15% by the bed, bedroom, or unit with a 5% extremely-low, 5% very-low, and 5% low-income mix.”

The current ordinance also temporarily allows the City Council “to consider a myriad of factors in determining whether to approve an alternative affordable housing proposal, such as whether the developer makes a large infrastructure or transportation contribution.”

The analysis found some challenges.

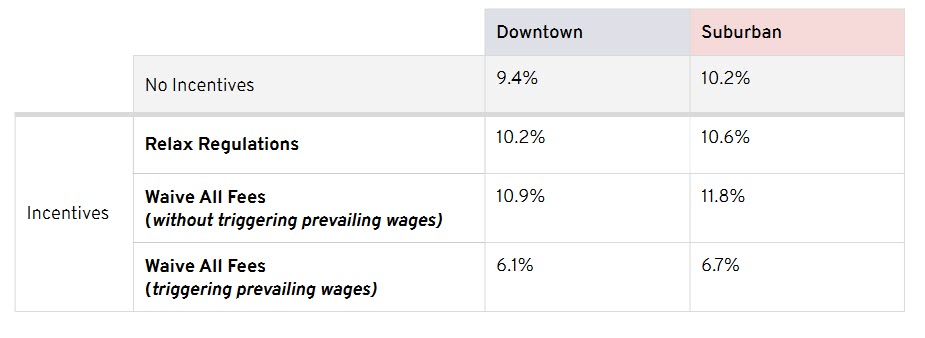

For one thing, market rate development scenarios “do not meet target internal rate of returns (IRR).” The target rate in both the downtown and outside the core is about 12% IRR. In the downtown, the rate is 9.4 percent and outside the core it’s 10.2 percent.

“With historically high construction costs, today’s development environment is challenging,” Cascadia found.

They note, “Hard construction costs in California were averaging at $222 per square foot in 2018. Costs have increased significantly since then. Between  2020 and 2021, costs increased over 10%, exceeding the historical annual average increase of 2-4%”

2020 and 2021, costs increased over 10%, exceeding the historical annual average increase of 2-4%”

Thus, “Given today’s realities, project costs are outweighing project revenue. Making it even more challenging for inclusionary zoning policies to be effective.”

They do find, “Development incentives that grow the revenue or reduce the cost of development can make it more feasible for developers to provide on-site affordable housing.” They add, “Most efficient way of growing revenue is by removing or relaxing land-use regulations that limit development potential.”

As the Vanguard has warned, in the downtown, “incentives to grow revenue are limited.”

They find, “Downtown’s new form based code does a great job at removing barriers to development. Unfortunately, this limits our options to offer development incentives as part of the policy.”

They do find, “Reducing parking ratios have a sizeable impact on financial feasibility of development.”

But not enough. Changing from 0.8 spaces per unit to 0.5 spaces creates an 8.5% change in IRR but it still takes it from 9.4% to just 10.2 percent.

Worse yet, outside the core, the incentives to grow revenue are even more limited.

“Residential high density zone encourages development that is denser than what is typically seen in areas outside of Downtown Davis and already removes commonly known barriers to multifamily development,” they find.

Further, “Reducing minimum parking and open space requirements to reach maximum density improves project feasibility but not by much.”

Taking it from 1.4 spaces per unit to 1 space per unit only results in a 3.9 percent change in IRR from 10.2 to 10.6 percent.

They found that the most efficient way of reducing costs “is waiving permit and impact fees.”

“Waiving fees have a bigger impact on financial feasibility, improving IRR by about 16%,” they write. “Waiving fees is considered a public subsidy, triggering prevailing wages that increase construction costs by 30%.”

But, even with incentives, our market rate building prototypes struggle to reach 12% IRR financial targe. “There are too few impactful or feasible development incentives that can help support an inclusionary zoning policy.”

There are trade-offs to creating inclusionary zoning policies.

One possibility: Maximize Number of Units but Less Affordable—Limited to units affordable to households making no less than 80% AMI (annual median income).

A second possibility: Deeper Levels of Affordability but Fewer Units—The share of units set aside is limited to between 5% and 10%.

Third: Maximize Number of Units at Deeper Levels of Affordability but Need Significant Incentives—Deeper levels of affordability but fewer units. This would require waiving a significant amount of fees.

They offer five critical conclusions.

First, “Given today’s high land and construction costs, the existing and interim inclusionary housing policies are not financially feasible.”

Second, “A feasible inclusionary housing policy needs to offer some level of incentives.”

Third, “Fee waivers can be impactful incentives, but they lose their impact when tied to prevailing wages.”

Fourth, “With few regulatory incentives to offer, a feasible inclusionary housing policy is limited in its ability to offer deeply affordable units.”

Finally and most importantly, “Inclusionary housing is not a stand-alone affordable housing strategy. There are other strategies to consider.”

“Given today’s high land and construction costs, the existing and interim inclusionary housing policies are not financially feasible.”

Why are land costs so high in Davis? Measure J of course. It makes land in the city 100 times more expensive than land for agriculture outside the city.

The entire Hibbert’s site could accommodate a very large Affordable housing complex. Which would require the same type of government subsidy as proposals located outside of the city.

But again, government funds pursued (and used) in Davis are then not available for other cities – where the need might be greater.

Unfortunately, Affordable housing (wherever it’s located) disincentivizes occupants from pursuing more income, in order to remain in their homes. (Unlike rent control.)

Davis already has quite a few Affordable complexes (one of which has reportedly created a lot of problems for neighbors and its own residents). Is there a “goal” in mind, regarding how many the city “should” have (and what the fiscal or other impacts are, at various levels)?

Or, is the city just blindly pursuing “more” – without even considering any of those type of questions? (Unfortunately, I think I already know the answer to that.)

And again, why isn’t the city even considering rent control, such as the ordinances that many other cities already have already enacted?

How do you figure that could happen? A private entity owns that land. They have a plan for that land. It would take a lot more than just funding to get an affordable housing complex there.

Now what the city could do is take land that they own and find a non-profit to develop affordable housing there, but it’s not going to happen at the Hibbert site.

The city controls the zoning, incentives (e.g., for density), and inclusionary housing requirements.

In any case, what’s the difference (from an owner’s perspective) between an Affordable housing complex on land outside of the city, vs. inside the city? Either way, they’re looking for a maximum return (while satisfying requirements for Affordable housing).

Affordable housing developers have some deep pockets, themselves. What makes you think that they can’t put together an offer that would be attractive to the owners? (Again, assuming that the city “encourages” this with the tools that they already have?)

Of course, the city has probably already lost some of the tools they could have used, when they approved the location for rezoning.

But perhaps more to the point:

How do cities such as San Francisco “meet” Affordable housing requirements (or encourage developers to do so)? One thing for sure is that they’re not looking outside of the city. They’re looking at land that’s already developed in some manner.

If you (or city officials) can’t answer that question, you have some more “work” to do, before you start advocating for more sprawl.

If “I” was in charge of things, I might base inclusionary housing requirements on the size of a parcel within the city. With larger parcels (such as Hibbert’s) requiring a higher percentage of inclusionary housing – due to economies of scale.

Along with other possible incentives, which ultimately might make an offer from an Affordable housing developer even more-attractive.

Just one idea.

But again, I’d look at cities which aren’t expanding outward, to see what they’re doing. That is, if I thought that increasing the supply of Affordable housing was preferable to rent control. (Some of those cities do both.)

Cool. Once you have purchased the property you can propose just that. Until then…

Wow, is that ever insulting…and untrue.

Because anyone with a passing interest in history knows that it doesn’t work. If you want to buy an apartment building and offer rent control to your tenants by all means do so. That way, only you will be harmed by your lack of interest.

Don’t share ideas? How much Affordable housing have YOU created?

Let me get this straight. You’re stating that the ONLY party that creates Affordable housing are private landowners? That’s factually wrong. In fact, they almost NEVER do, on their own. And would never do so if not required to by regulation, and/or government funding.

At least TRY to put forth something other than complete nonsense.

How so? Be specific, in regard to income limitations in regard to Affordable housing. And (I realize this is “hard” for you), but try to do so without putting forth unexplained, insulting comments of your own.

Apparently, you have an “argument” to pick with large numbers of tenants, tenant groups, and cities which have successfully implemented rent control.

Maybe you should go speak with some of those tenants, and tell them that you don’t support the rent caps they enjoy. I’m sure you’ll get a “warm welcome” regarding your thoughts.

1. Developer fees are calculated based on each new units cost share of existing infrastructure plus costs of new infrastructure needed by the new units. Waiving fees means existing residents are subsidizing new units. That is a policy decision but everyone needs to be aware of cost ramifications

2. Ag land prices reflect current zoning. If rezoned to residential, those prices will directly parallel current in-city land prices.

3. Measure J requires citizen participation in land rezoning. For me what is most important is it adds an added level of ag land protection. When situated in the center of ag land one can overlook how important this is place is with deep soils, gravity fed irrigation, and a Mediterranean climate (although this is changing with climate change.). This is more important as our oceans continue to be fished out.

This is extremely complex. Limited equity housing, smaller starter homes, denser housing, taller buildings, more homes with less affordability, and subsidized rentals are all part of the toolbox. There are impacts from more people. Those require more funding to mitigate. Oh, that’s developer fees?

We do have a responsibility to keep trying.

But Ag land protection is not a problem. Plenty of land has been placed in conservation easements throughout the area. I would simply ask how much is enough? In fact since the passage of Measure J much more land has been preserved through conservation easements than has been developed.

Ron, ag land must be looked at on a global scale and not based on local conservation easement acreage. The Russian war on Ukraine illustrates what a disruption on world food can result in famine. It too is complex with where food is grown, how it is transported, who controls seed production and food processing, and even the quality of our food and biodiversity of the soil and food ecosystems all exacerbated by climate change. We must hedge our bets and continue to protect as much ag land as we possibly can. I mean it is about our food.

Bob, that is soo 20th Century, limits to growth, Club of Rome, scarcity in a place of abundance stuff that a younger person who wants a home might dismiss it as boomer talk.

Reminds me of my mom, post WWII trying to get me to eat my vegetables, saying people are starving in Europe.

Food scarcity in Yolo County? I don’t think so.

But let me ask two questions to demonstrate the fallacy of your thinking.

Which would have a smaller Carbon footprint, UCD workers commuting from Covell Village or those same people commuting from Woodland?

Which is likely to lead to greater food security, building student housing on research fields on campus or on commodity production land outside the city limit?

What I find sad is that UCD has and continues to do research that has improved both the quantity and quality of food throughout the world. Research in drought resistant corn and wheat crops, chick pea genetics, rust resistant wheat and metabolic pathways for nitrogen fixation come to mind off the top of my head. Facilitating that work is where the real future returns are to be found, not in preserving land that can be annexed into the city to house its citizens.

Oh just one more point Bob, and I know this will bother Don but its true, farmland isn’t what is limiting in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys. Water is what is limiting and we can move the water.

One of the things that I find very surprising about this analysis is that there is no attention paid to what the internal rate of return change would be if market rate rents were increased. What percentage increase in market rate rental rates would be necessary to achieve the target internal rate of return?

Increasing rents is surely one of the tools in the toolbox. That way, the market rate apartments would generate more revenue for the developer, and therefore be able to subsidize greater levels of affordable units.

The obvious problem with that tool is that it makes market rates of apartments, less affordable; however, since the majority of rentals in Davis are rented by UC Davis students, many of whom have deep pockets for parents does increasing the market rate rents really hurt Davis?

It certainly hurts the UCD students whose parents are not well off financially, but since it’s only one tool in a multi tool toolbox, coming up with a tool to address affordable units for UCD students that have fiscal need would be a necessary byproduct. UCD and the state of California could step up with scholarship programs to provide financial assistance to UCD students with demonstrated financial needs.

Yeah Matt, stick it to the college kids and their families. Nice.

Ron, if this were policy rather than simply an analysis study to hep educate the City on what the “playing field” looks like, you would have a point. But it isn’t policy. Trying to make a wise policy decision without complete data is more often than not a fool’s errand.

The way this analysis comes across is as a “woe is me (us)” throwing of the hands up in the air, which means Davis won’t get any Affordable housing units because no project with such units “pencils out.”

This study appears to take one parameter as given–the underlying land price. The fact is that land value varies by its scarcity and demand. That’s why land in Texas, where fewer people find it desirable, is much less than it is in California. (BTW, California cities ranked as the “happiest” in a recent report: https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/happiest-bay-area-city-17712009.php). For Davis, the developable land is restricted through both zoning and incorporation. That’s why ag land, which still needs to go through those procedures, is priced so much lower. If more surrounding land it available for development, like in Woodland, then the land prices go down EVERYWHERE in Davis because the supply has increased. That lower land price then makes more housing projects, including infill, more feasible.

As for protecting ag land, we must think holistically. Does protecting the few acres next door protect as much as having compact development here that reduces more sprawling development in Elk Grove or Fresno or even Texas? I’m pretty sure that our policies are in fact destroying more ag acreage that what’s being preserved.

Those places would continue sprawling, regardless. Folks like you are ‘in charge”, there.

And given that much of the sprawl is from migration out of the (more-dense / environmentally responsible) Bay Area, how does encouraging this migration “save farmland”?

Ultimately, there are relatively few cities which even attempt to save surrounding farmland and open space in a serious manner. And the few that attempt it are under constant attack from folks like you.

And by the way, since many of the “happiest cities” you cite are supposedly in the Bay Area (which takes aggressive action to preserve their remaining open space), are you sure that’s the comparison you want to use? While simultaneously “knocking” sprawling hell-holes like Texas (as the “model” you strive for)?

Ultimately, you can only preserve land in the relatively few places that welcome those efforts in the first place. And unfortunately, folks like you STILL attempt to undermine it – even in those few places!