By Stephen James and Fred Johnson

In a significant decision benefiting reporters and citizen journalists, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals last week ruled in favor of journalists’ right to record in areas open to the public, even secretly, after a lawsuit challenged an Oregon state law that required consent to record private conversations.

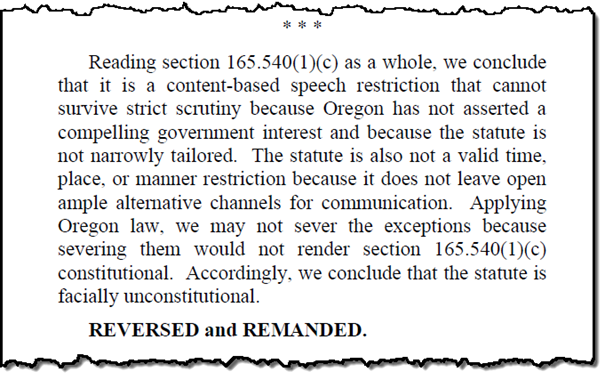

The decision was authored by U.S. Circuit Judge Sandra Segal Ikuta, who wrote that “[O]regon’s law is a content-based restriction that violates the First Amendment right to free speech and is therefore invalid on its face.” A three-judge panel issued the 2  -1 opinion, with Judge Carlos Bea joining with Ikuta.

-1 opinion, with Judge Carlos Bea joining with Ikuta.

Judge Morgan Christen disagreed with the majority and filed a dissenting opinion. Courthouse News Service summarized Christen’s objections.

U.S. Circuit Judge Morgan Christen wrote in dissent that Oregon adopted its law with a goal of ensuring that Oregonians would be free to engage in the “uninhibited exchange of ideas and information,” without fearing that their words would be broadcasted, disseminated or “worse, be manipulated and shared across the internet devoid of relevant context.”

Christen accused the majority of rewriting the state’s articulated purpose for the law and recasting its interest as one in “protecting people’s conversational privacy from the speech of other individuals.”

Veteran San Francisco Chronicle courts reporter Bob Egelko summarized the origin story of the controversial group that brought the lawsuit.

The Oregon law was challenged by Project Veritas, a nonprofit right-wing organization whose members have posed as liberals in undercover actions to expose alleged left-wing bias in the media and elsewhere, and have occasionally been found guilty of crimes in those actions. But the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with the group that the law was an invalid “content-based restriction on speech.”

In an interview with the Davis Vanguard, Project Veritas attorney Benjamin Barr expressed satisfaction with the win, and emphasized the application of the First Amendment to the case.

“I was pleased with the reasoning of the Ninth Circuit in that it understood that what you convey in public to others cannot properly be the subject of privacy,” Barr explained. “After all, Oregon was trying to make this case about protecting conversational privacy and how if it kept the law in place, it secured First Amendment rights because people would feel more free to speak in public.”

Barr also emphasized that the case would benefit citizen journalists. “[Oregon] ignored the equally weighty First Amendment rights of citizen journalists who have a right to gather information in public places,” he said. “It can’t be the case that pretend privacy bubbles float around everyone in the State of Oregon to preserve their speech rights and newsgatherers receive no First Amendment protection.”

In an email to the Vanguard, Zachary Kramer, senior associate general counsel of Project Veritas called the ruling historic, and predicted that the group will seek to challenge similar laws in other states.

“The impact of this historic decision is not limited to Oregon. It is our hope that two-party consent recording laws in states like California and Washington will soon be successfully challenged by Project Veritas as unconstitutional,” Kramer said. “Our attorneys, Ben Barr and Steve Klein, enabled a great win for undercover journalists.”

First Amendment Coalition Executive Director David Snyder agreed that the decision would not apply in other states, including California.

“I don’t think this ruling applies in California, or in other states where the laws regarding the non-consensual recording conversations do not encompass conversations in public space,” Snyder said via email with the Vanguard. “The 9th Circuit in this case focused on the fact that the Oregon law covered conversations in public, where people have no reasonable expectation of privacy. California’s law does not do that, and I believe there are a number of other states that do the same.”

Snyder further emphasized the distinction between the Oregon law, and California law related to recording in public vs private space. “The court here thus affirmed the First Amendment right to record in public space,” he said. “It also focused on the fact that the Oregon law was ‘content-based,’ that is that it discriminated on speech based on its content – specific types of speech are subject to the law, while others are not. California’s recording law does not do that – it treats speech of differing content the same.”

In her coverage of the decision, Courthouse News Service reporter Alanna Madden pointed out that, under journalism ethical standards, the tactic of secretly recording sources or subjects comes with a caveat. It should be used only as a last resort, when important, newsworthy information cannot be obtained through customary reporting methods.

While Oregon is only one of five states that prohibit individuals from recording conversations without notice or consent, most professional journalists identify themselves and inform their subjects if they are recording a conversation. Indeed, when it comes to the style of reporting favored by Project Veritas, the Society of Professional Journalists recommends in its Code of Ethics to avoid “undercover or other surreptitious methods of gathering information unless traditional, open methods will not yield information vital to the public.”