By Susan Bassi

In the summer of 2019, while covering a taxpayer waste lawsuit in Judge Brown’s Sacramento courtroom, I stumbled upon a group of young men—casually dressed, heavily tattooed, remarkably polite, and confidently wielding cameras in the courthouse. They introduced themselves as cop watchers and First Amendment activists. Their names sounded like MMA fighters, not traditional journalists.

Without business cards they shouted out names including N2Film, Tulare Cop Watch, NateSkates182, San Joaquin Valley Transparency and a visitor from New Jersey.

Behind the names were people who would introduce me to the cop watching community. These cop watchers were plainly journalists, yet their names did not appear on the membership  lists for Investigative Reporters & Editors, Society of Professional Journalists, Online News Association or the ACLU, as traditional journalists often are.

lists for Investigative Reporters & Editors, Society of Professional Journalists, Online News Association or the ACLU, as traditional journalists often are.

Over the next several months, cop watchers from all over the country generously shared their video editing and uploading tips. They fearlessly recorded police encounters and educated hundreds of thousands of people when it came to civil rights. Their work was contagious, part education, part entertainment, it was something different. It was hard to define.

Cop watchers taught folks not to talk to cops, and not to present ID unless they were officially detained. Mostly they encouraged others to join them as they were becoming a movement like none we had ever seen.

Cop Watchers have had a significant impact when it comes to police misconduct. They likely influenced a young 17-year- old who knew to record Derek Chauvin sitting on the neck of George Floyd during the pandemic, as traditional journalists hoovered inside with their comfortable union pay and PPP money.

Just before the pandemic upheaval, Camera Joe came to Los Gatos for my first official audit. Part improv and part journalism, there was no plan or script. We were winging it, teaching each other. Cop watching and First Amendment Auditing is always better with a partner. That is rule two.

Our first stop: the Los Gatos police station for a public records inquiry. Live streaming added pressure. Each word was a potential exhibit in court, or a piece of history visible to our children, family members and friends.

The scenario inside the station was novel and riveting. An unintentionally rude comment from Camera Joe couldn’t be edited out, leaving me feeling apologetic yet determined. Over a hundred viewers tuned in, some urged the mayor to produce the records. The video transformed a mundane records request into an enthralling journalism experiment.

“Tell them NOT to call the red phone,” Camera Joe exclaimed, provoking the lobby phone to ring—a surreal and thrilling experience vastly different from a solitary desk assignment for traditional public records submissions.

Despite not securing the records, the attempt wasn’t futile; over 200 people witnessed our endeavor.

Next, we chased down rumors of a body buried behind Gardinos, joining mainstream reporters to observe San Jose Police’s dig that would appear on the nightly news. Despite mingling with familiar faces of media colleagues from KTUV and NBC Bay Area, we departed for an unscripted cop watch. By chance, we captured a police interaction in downtown Los Gatos.

Immediately we recorded an arrest and forced mental health hold that resulted after an employee from the local Apple store called police to say a transient made her nervous. Shortly thereafter the transient’s arrest happened on the very spot Apple co-founder, Steve Wozniak, was known to sit and wait for the latest iPhone or other Apple product release.

When the pandemic struck, our plans became uncertain. However, the eruption of protests following the death of George Floyd sent us into the streets of downtown San Jose.

There we found a scene that mirrored Berkeley protests of the 1970s where students upset over U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War clashed with police.

The scene in San Jose in 2020 happened live. In color. Not on a television screen. Was teargassed while trying to walk down the middle between protestors and police. I reported on my YouTube platform what getting teargassed felt like, despite having no hair and make up person to make me look like a tv reporter.

Wondered what my great-great grandmother would have thought of my recording the police down the block from where she had lived 70 years earlier. Wondered what photos my great-great grandchildren would see and what they might be told about my work three generations from now.

Recently, are captured images at courthouses and law enforcement offices in Southern California. Most shocking were limitations on public recording in all courthouses, despite the ubiquitous presence of surveillance cameras and the federal right to record police contacted to work in those courthouses.

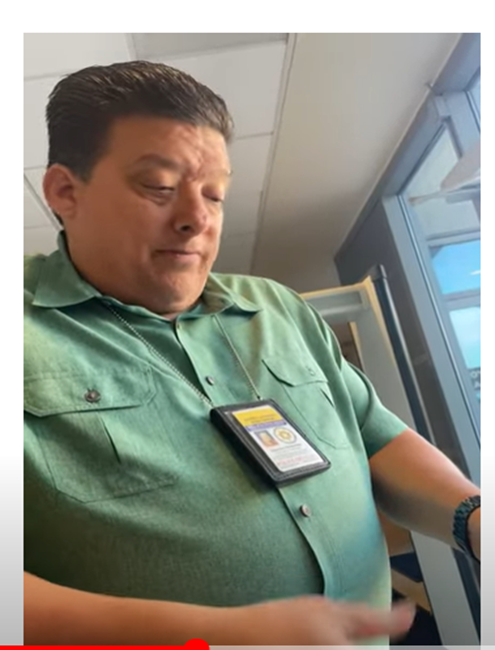

The Davis Vanguard inaugurated a weekly column, “Records Revealed,” aimed at illuminating the significance of public records and how to access them. Last week the column was delayed as we faced opposition to our public records request while recording in the San Bernardino District Attorney’s Office. Now we wait to see if the court will apply a well-known cop watcher rule: When you are fearful or the government begins to bully, Go Live Or Go Home!

In the evolving landscape of journalism, we’ve witnessed the decline of newspapers as well as a lack of inspiration and financial sustenance for watchdogging local government and courts. Therefore, we are reinvigorating our records column, urging readers to engage, and reviewing family court files to compete our assignments.

Our hope is to inspire a collective effort through journalism to properly provide information to the public about the courts, police, private judges court appointed minors counsel and a duly elected district attorney, such that our reporting can have meaningful impact. Especially with respect to family court, where no cameras are allowed.

Susan Bassi is a print publisher, freelance photographer, investigative journalist, embedded cop watcher, family court watcher, mother, grandmother and dedicated public records advocate. Her activism includes working to get cameras in all California’s public court proceedings and mandated reporting with respect to judges who consider private judging over public service.