By Fred Johnson and Susan Bassi

The Davis Vanguard is excited to introduce “Records Revealed”, a weekly column that aims to give readers a behind-the-scenes look at the public records used by investigative journalists when reporting on police, local government, attorneys, elections, and the courts.

Approximately 90% of the work done during the investigative reporting process ends up on the editing room floor, never making it into published articles. The weekly “Records Revealed” column aims to capture some of this information, which may pique public interest, inspire hyperlocal reporting, or disseminate social media content containing factual information about local government and courts.

Public records contain valuable information regarding government operations.  Traditionally, public records have been sought after by journalists, filmmakers, attorneys, students, interns, and citizens interested in obtaining information on everything from government budgets, water board allotments, elections, fire department response times, police officer training, school administrators, taxes, city planning, and development, to environmental concerns, food safety, nonprofits, courts, and animal control.

Traditionally, public records have been sought after by journalists, filmmakers, attorneys, students, interns, and citizens interested in obtaining information on everything from government budgets, water board allotments, elections, fire department response times, police officer training, school administrators, taxes, city planning, and development, to environmental concerns, food safety, nonprofits, courts, and animal control.

The Washington Post recently unveiled a similar series by Nate Jones, focusing on FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) records obtained from the federal government. In contrast, the Vanguard’s new column will focus on records obtained under California’s Public Records Act (CPRA), which applies to state and local agencies.

Additionally, as part of the Vanguard’s investigative series, Tainted Trials, Tarnished Headlines, Stolen Justice, this column will emphasize records obtained from the public domain, political campaigns and from the judicial branch, including courts.

The judicial branch is exempt from CPRA, but California Rules of Court, which essentially mirrors CPRA at Rule 10.500, seeks to provide public access to the court’s administrative records.

Adjudicative or court judicial records are obtained from court files and can be found in the county where the legal proceedings take place. This adjudicative record was obtained from Orange County family court in connection with the divorce case of state senate candidate Katie Porter, who filed a request for a restraining order against her former husband during their divorce. She recently denied allegations of domestic violence after her former husband claimed she was the aggressor in the relationship. (left)

Court administrative records are obtained by making a request pursuant to California’s Rules of Court, Rule 10.500 to the court’s public information officer. This letter is from the Orange County Superior Court Public Information Officer notifying the requestor that the court will take more time to produce requested court administrative records. (right) Graphics by Susan Bassi.

Each week Records Revealed will highlight public records that provide insight into the rigorous work involved in investigative reporting, a crucial function of the free press. The weekly column aims to engage readers in the investigative process with an eye toward promoting critical thinking and participation in the fact gathering process necessary for complex media investigations.

Where to Get Public Records, and How

In 2017, the McManis Faulkner law firm was praised by journalists in connection with a lawsuit brought on behalf of Ted Smith. The case establishes the obligation of state and local agencies to produce emails in response to records requests. The final decision in this lawsuit assures that the public can obtain information about the business of the government, even when that business is contained in government or personal email accounts.

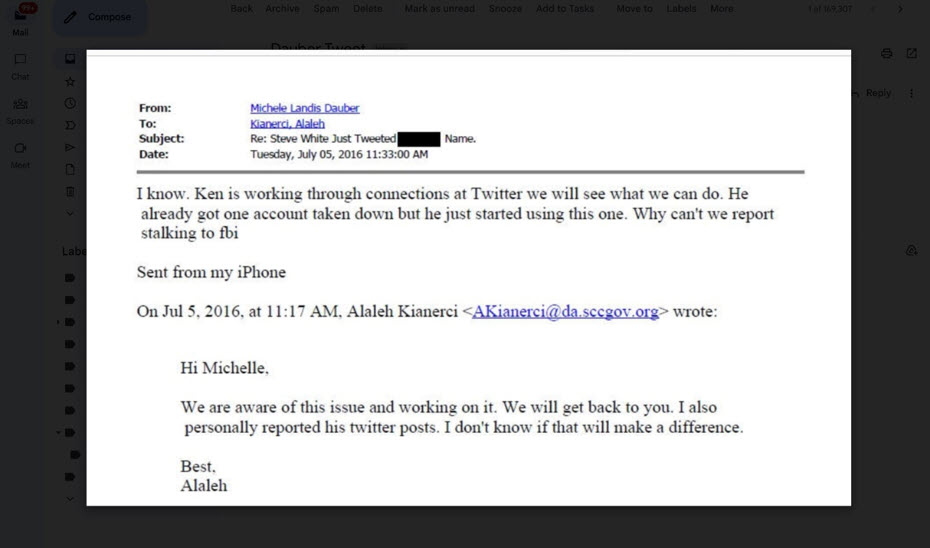

This legal precedent was used by journalists to request records in Santa Clara County related to the recall of Judge Aaron Persky. In response to the request, the county produced over 500 emails exchanged between Stanford University law professor, Michele Dauber, and high-ranking members of the Santa Clara County District Attorney’s Office. The emails were sent over the three-year period before the June 5, 2018 election when Persky was recalled.

The 573 emails produced by Santa Clara County in response to the public records request reveal misuse of county resources as Deputy District Attorney Alaleh Kianerci, and other high ranking DA office employees, directed information to Dauber’s political campaign to assist her efforts to recall Judge Aaron Persky.

Political campaign records can be obtained by making a request to the local counties where a political candidate runs for office. Records can also be obtained from the Fair Political Practices Committee (FPPC), a state agency charged with watchdogging the state’s elections.

Information available related to political campaigns includes details about campaign financing and expenditures. Public records, and information in the public domain, reveal James McManis, who represented Judge Persky during the recall, was actively involved in Persky’s political funding, along with his associate counsel, former FPPC employee, Ann Ravel.

James McManis and Ann Ravel were frequent attendees and members of the secret BBMP (Bench-Bar-Media-Police) judge club where they mingled with the judges ruling in high-profile legal matters, as their opposing counsel did not.

Police, Politics and Public Records

Public pay related to police and public officials can be found by searching public websites including Transparent California, the state’s largest public pay and pension database. The website discloses salaries of football coaches earning over $5 million in annual compensation.

The website also shows pay for public employees including librarians, teachers, elected officials, doctors, and police officers. Governor Gavin Newsom’s public compensation can be found on the website as well.

In 2020, California passed SB1421, a law that amended California’s Public Records Act, as championed by Bay Area lawmaker, Nancy Skinner. The new law expands public access to information about police misconduct.

Law enforcement agencies are now required to produce records related to individual police officers when they are involved in any of the following:

- An incident involving the discharge of a firearm at a person by a police officer.

- An incident in which the use of force by a police officer resulted in death or great bodily injury.

The law also requires agencies to produce records related to findings that a police officer engaged in dishonesty in the reporting, investigation, or prosecution of a crime.

Finally, the new law requires production of records that contain information that a police officer engaged in sexual assault involving a member of the public.

The new law saw the production of police email records that revealed Santa Clara County Victim Witness Services Director, Kasey Halcon, and her subordinates, Saher Stephan and Nida Rehman, were involved in moving a victim of sexual assault (publicly known as Celeste Guap), out of state. It was reported Guap had been sexually assaulted by multiple police officers working for departments across the San Francisco Bay Area.

Moving Guap out-of-state made it far less likely she would testify in any criminal case against the officers who assaulted her.

Shortly after the time the email records were produced, court records show Nida Rehman and Saher Stephan divorced their respective spouses, and became intimate partners.

Around this same time local news reports driven by public records requests reported that from 2013 to 2018, there had been at least 30 formal complaints about sexual harassment lodged against employees in the Santa Clara County’s District Attorney’s Office. An office managed and supervised by Jeff Rosen.

Finding Public Records in Public Court Files

Legal proceedings and public court records can tip journalists off to the existence of public records that can be formally requested to obtain further information.

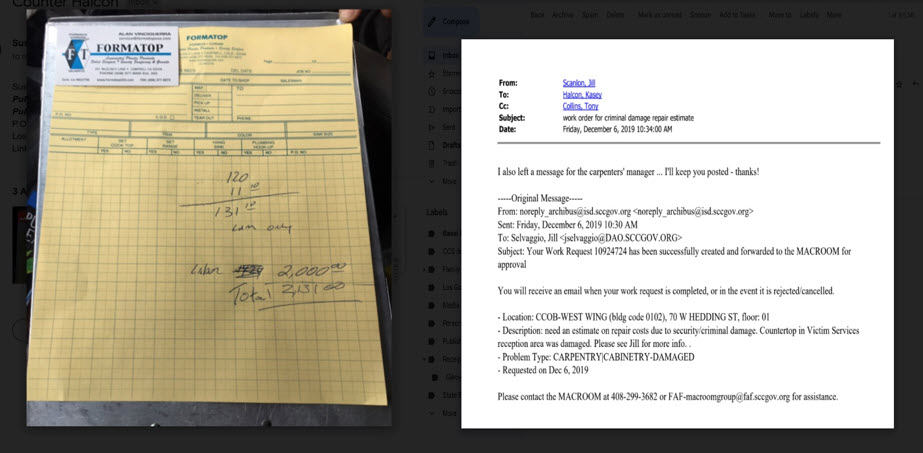

By way of example, Santa Clara County District Attorney’s Victim Services Director, Kasey Halcon, mishandled a mental health crisis involving a crime victim back in 2019. The alleged victim expressed frustration that Halcon and her staff had not provided services taxpayers seek to assure crime victims. Nor complied with Marsy’s Law, which seeks to define crime victim’s rights.

While exhibiting signs of a mental health crisis, the victim allegedly pounded his fist on the counter while holding a sharp object, leaving behind a mark on a counter in Halcon’s office.

Court documents show Halcon requested the victim repay the county for a contractor she selected and approved to repair the counter at a cost of $2,131.

Following the Money Found in Public Records

By comparison, when the Berkeley Police Department was vandalized during the protests related to the death of George Floyd, public records reveal the cost to clean up vandalized walls, windows and other structures was $7,209,57.

The invoice produced from a records request to the city included details of the costs for the cleanup. Costs that included a supervisor, skilled labor, paint, and materials from the local ACE Hardware store.

Public records can also show spending practices of local officials. In 2019, a records request was made after a number of local residents complained Santa Clara County Supervisors were spending lavishly on meals for themselves, their family members, and their political supporters.

Records produced by the county show Supervisors hosted a swanky reception catered by Scotts Seafood in the county’s public lobby. Food provided to the elected officials and their invited guests, at taxpayer expense, included artisanal salads, smoked salmon, crab cakes, cheese platters, tofu kabobs, pita bread with hummus and Tzatziki sauce.

The event infuriated local voters critical of the wasteful spending practices, mindful many in the county struggled with food and housing insecurity. Supervisors Mike Wasserman, Joe Simitian, Cindy Chavez, and Susan Ellenberg’s incurred $7,397.32 in public expense for the event. More than the entire cost of cleaning up vandalism of the Berkeley Police Department.

Have questions about public records, or records to share? Please email The Vanguard, along with a request for consideration to be included in this column. Click on the links in each story to learn about public records and how to go about finding them.