By Susan Bassi and Fred Johnson

Judge Lawrence Riff of Los Angeles County Superior Court once told a group of divorce lawyers that they were essentially first responders. Now Judge Riff has written a letter to the son and widow of slain Maryland family court judge, Andrew Wilkinson, calling the deceased family court judge a hero.

It is unlikely there will be a letter to the children of Pedro Argote, who reportedly endured horrific abuse by the man suspected of murdering a family court judge in connection with their parents’ divorce case.

According to news reports, the family court and children’s court-appointed minors counsel, Ashley Wilbur, repeatedly failed to provide protection for Argote’s former wife and children. Now Wilkinson’s son and Argote’s children will forever be tied to the inadequacies of family court as it relates to domestic violence, child abuse and murder.

A spouse subject to a restraining order is not only prohibited from owning firearms but additionally faces limitations when it comes to prospective employment. A DVRO may prohibit a former spouse from obtaining employment as a real estate broker, police officer, public school teacher, or even as a dog catcher.

Additionally, in California, a DVRO can add costs to family law litigation in the form of attorneys’ fees, alcohol testing, professionally supervised visitation, court-approved parenting or batterers classes and expensive therapy. Expenses that quickly become financially crippling when family law cases are allowed to drag on for years.

Surprisingly, often times parents subjected to DVRO arising from a divorce or custody case show no prior history of criminal or mental health impairment.

Legal Abuse Syndrome

Dragging a former spouse through the legal system for years, and threatening them with financial ruin or jail, appears to drive spouses to pay divorce lawyers to engage in abuse by proxy.

“Legal Abuse Syndrome”, as defined by MFT Karin Huffer, is not recognized by judges or lawyers. Instead, coercive control is defined by California’s Family Code and addresses only conduct of spouses involved in the state’s family courts.

Freelance reporter Mike Volpe recently covered Silicon Valley divorce cases involving insider attorneys BJ Fadem, Nicole Myers and private judge Michael Smith. Volpe described how highly paid divorce lawyers can drag cases out for years, preventing a spouse, especially a self-represented spouse, from moving forward with their life.

Volpe describes how an emergency request to the family court can derail a former spouse who must respond to the request in 24 hours, regardless of work obligations or schedules with children. Often, these requests are not emergencies but rather litigation tactics used by unscrupulous divorce attorneys.

The Vanguard recently surveyed over 100 California attorneys acting as minors counsel in family law cases. The survey sought comment on the cost and effectiveness of court appointed attorneys for children at the center of cases where abuse is alleged or directly observed. One survey respondent who wished to remain off record, stated:

” In my opinion, in general, most attorneys charge too much. Too many of them turn their offices into billing machines. Too few people understand the cost of litigation when they get started with it, and too many attorneys fail to help their clients understand that better. Too many people have the attitude, ‘I would rather pay $1,000 to my lawyer than pay $10 to my ex.’ Too many lawyers are willing to support that attitude.”

As to the purpose and cost of attorneys representing children, the family law attorney went on to say:

” The children’s attorney should work to minimize the negative impacts of the conflict on the children. So, that attorney may actually do an excellent job, help put the children in a position where their exposure to their parents’ conflict is greatly reduced, cause the conflict over the child to subside or at least stay out of court, and meanwhile the child has little idea what happened and never ends up finding out about it. The parents, on the other hand, may very well both hate that attorney because he or she made them stop fighting with each other in court. So, the good attorney who actually does his or her job well may end up becoming everybody’s favorite scapegoat. It’s another reason why relatively few attorneys want to do this type of work.”

As previously reported by the Vanguard related to Santa Clara and Contra Costa counties, a core group of attorneys are willing to take such work at staggering costs to parents and taxpayers.

In justifying the expense of minors counsel in cases involving domestic violence allegations, judges and lawyers are quick to label these cases “high conflict.”

What Can Judges Do about Domestic Violence and How Much Will it Cost?

Men and women seeking protection from domestic violence frequently complain the police rarely investigate and instead direct complaining witnesses to the family court.

In the week between the murder of Judge Wilkinson and Argote’s reported death, a California Bench Guide published to assist family court judges better address domestic violence restraining orders.

Perhaps as a Judicial Branch response to Piqui’s law, recently signed by Governor Gavin Newsom, the guide was published under the supervision of Kern County Superior Court Judge Susan Gill and Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Mark Juhas.

The new guide seeks to educate judges, when it comes to issuing DVRO restraining orders, or not. The report describes abuse as:

- An intentional or reckless cause/attempt to cause bodily injury

- Sexual assault

- Placing a person in reasonable apprehension of imminent serious bodily injury

- Threatening

- Battering/Attacking/Striking

- Harassment

- Stalking

- Telephoning/Annoying calls

- Destroying personal property

- Molesting

- Impersonation

- Disturbing the peace, which includes coercive control

- Reproductive Coercion

- Violating a restraining order

- Abusing the other party’s child, if that disturbs the party’s mental and emotional calm

The new Bench Guide also goes on to explain coercive control to family court judges, noting:

“Coercive control is a pattern of behavior that unreasonably interferes with a person’s free will and personal liberty. Examples of coercive control include but are not limited to unreasonably engaging in:

- Isolating someone

- Depriving someone of basic necessities

- Controlling, regulating, or monitoring someone’s movements, communications, daily behavior, finances, economic resources, or access to services

- Making threats related to someone’s actual or perceived immigration status

- Engaging in reproductive coercion, which includes using force, threat, or intimidation to pressure someone to be or not be pregnant; or to control or interfere with someone’s use of birth control, contraception, pregnancy, or access to health information.

A court may grant a request where no physical violence or threat of physical violence exists, based solely on harassment, coercive control, and/or one of the other forms of abuse.”

For individuals involved in prolonged divorce cases with an imbalance of legal representation, the new Bench Guide seemingly stands to educate judges with respect to Legal Abuse Syndrome.

Will Judges Do Better?

A spot audit of cases before Judge Susan Gill and Judge Mark Juhas indicates that the judges selected to guide other judges on the topic of domestic violence restraining orders may not have been the best choice.

Middle-class and high asset divorce cases involving allegations of abuse, or coercive control, appear to regularly include the addition of minors counsel, without data to support the appointment and expense being justified.

The Vanguard is reviewing Judge Gill’s cases that involve minors counsel Stephanie Childers. Childers was appointed to the bench as a judge alongside Judge Gill in the Kern County Superior Court only months after filing her minors counsel qualifications for 2023.

Additionally, Judge Gill is bound by new case law created after her colleague, Judge Stephen Schuett, refused to assure attorneys fees to the wife in the Knox divorce. Arguably, one spouse willing to pay lawyers while financially starving the other spouse in a drawn-out divorce is abusive based on the new judge guide definitions.

Judge Mark Juhas of Los Angeles Superior Court is currently presiding over a divorce case involving mutual restraining orders.

Before the new judge guide was announced, Judge Juhas was decorated with an award presented by the California Lawyer’s Association and the Judicial Council, suggesting he close connections to attorneys who would bring him business should he decide to leave his public court position in favor of more lucrative work connected to private judging.

In the new guide, Juhas and Gill note the potential risk of judicial bias in cases of mutual restraining orders, as social science shows judges expect “victims to be sweet, kind, demure, blameless, frightened, and helpless,” and not multifaceted people.

The Vanguard is currently reviewing the case files assigned to Judges Gill and Juhas and anticipates making media requests where appropriate.

Not All in the Family

In addition to family law cases, an alarming number of civil restraining orders appear to being issued that seemingly seek to chill speech.

As previously reported by the Vanguard, divorce attorneys Hansen and Volkov used the courts and a restraining order case in a manner a higher court deemed improper.

More recently divorce attorney, private judge and minors counsel BJ Fadem used the courts to obtain a restraining order against the aunt of minor children Fadem represents in connection with a decade-long divorce case. In that case, the conflict appears largely related to Fadem’s appointment as minors counsel, which resulted in the father being hospitalized for a mental health evaluation immediately after Fadem was appointed.

Elise Mitchell sought to use the family court to restrain and jail a mother who lost care, custody and control of her children at Mitchell’s recommendation. Mitchell complained the mother had been posting photos of her 10-year-old twin daughters on Tik Tok after Mitchell had spent months using the courts to keep their mom from contacting them, even for their birthday.

Judge Vanessa Zecher denied the Vanguard’s media request to remotely attend the hearing where Mitchell’s request to sanction and jail a mother for posting on social media was set based on Mitchell’s emergency request.

Mitchell did not return the Vanguard’s request for comment on the appropriateness of children Mitchell represents maintaining Tik Tok accounts in violation of the platform’s policies.

Paper Protection for Judges

Paper Protection for Judges

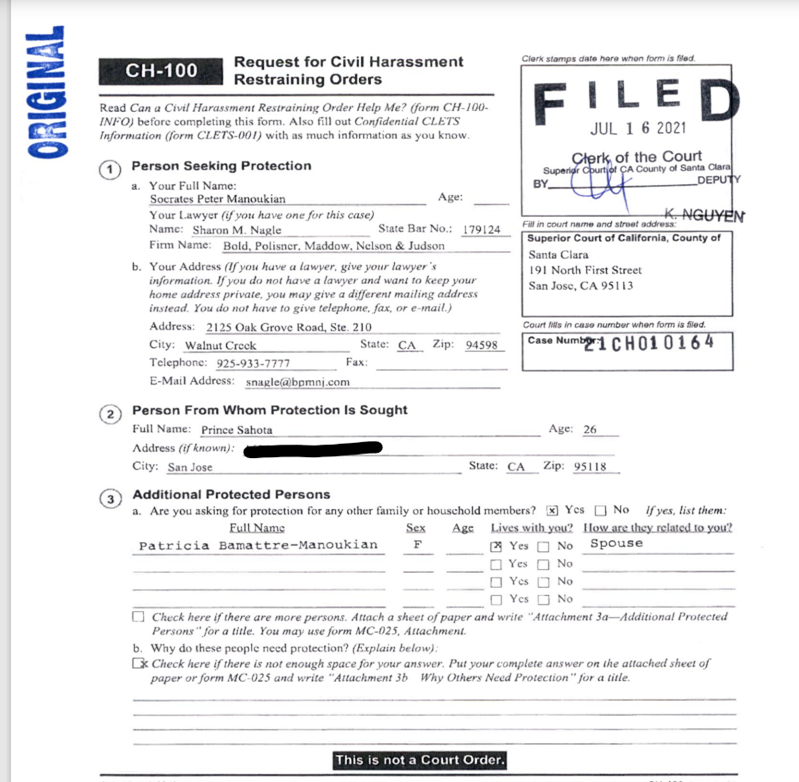

Santa Clara County Judge Socrates Peter Manoukian obtained a restraining order against his former judicial intern. The court filings in the civil restraining order application indicate the intern called and harassed Judge Manoukian over 41 times in one day. The former intern also sought out the judge’s home address.

Arguably, Judge Manoukian’s restraining order request may garner public empathy, and rise to an acceptable level to justify a civil restraining order. However, in too many cases these orders are requested more to chill speech and control litigation.

Seemingly, folks’ need not be in the crossfire of family courts to get caught in the crossfire of the mental health and abuse crisis that surrounds them.