This week’s Records Revealed column focuses on public records related to cameras in courtrooms and costs for virtual hearings that allow court users and members of the public to remotely appear in court.

By Susan Bassi and Fred Johnson

For years police departments and police unions bitterly resisted body worn cameras (BWC). Not surprisingly, as the technology was implemented, it revealed a cop culture defined by unjustified shootings, harassment, excessive force, racism, sexism, and selective enforcement. Court watchdogs assert a similar culture exists when it comes to judges and public courtrooms.

For over 60 years California’s Judicial Council has been forced to consider the issue of cameras in courtrooms consistent with open government policies. The first rules related to the issue were adopted in 1965. Several years later the judges complained media coverage interfered with an individual’s right to a fair trial, so the rule was altered to prohibit photographing and recording court sessions and recesses.

By 1979, then- Chief Justice Rose Bird commissioned a committee that ultimately led to rules that permitted media coverage in criminal cases, and in the court of appeals. However, as the public demanded more access and transparency, California’s Chief Justice, Ronald M. George, established the state’s first public Bench-Bar Media (BBM) Committee to foster a better relationship among judges, attorneys, and journalists.

Through a robust public process, the BBM met over a two-year period. From 2008 to 2010, publishing an initial report entitled “A Balancing Act,” Accommodating the Needs of the Bench, Bar, and Media in Pursuit of Justice. The report included 11 formal recommendations, the most important calling for a change in the court rule dealing with cameras in courtrooms. The recommendations were unanimously opposed by California’s judges.

Judges Have Long History of Complaining About Cameras in Courtrooms

In response to the initial BBM recommendations, judges complained that media interests dominated the committee. Judges also complained the committee failed to adequately research and analyze the problems identified by the committee. Further, disgruntled judges complained BBM recommendations encroached on judicial discretion.

Ultimately, the BBM issued a final 374-page report in 2011. BBM appointees contributing to the report included judges, attorneys, and members of the media. The report documented a transparent and robust public participation process.

The report also revealed the existence of a local committee in San Joaquin County but made NO mention of the secret Santa Clara County Bench – Bar- Media Police Committee (BBMP) group that had operated in Santa Clara County since 1988 until it was exposed by the Vanguard over a decade after the 2011 report was published.

Retired Santa Clara County Judge Jamie Jacob- May was appointed to the BBM early on. However, she was designated as a “former” BBM member by the time the final report was published. From the time she was employed as the Santa Clara County Superior Court presiding judge, to the time she was appointed to the BBM while working as a private judge for JAMS, Jacob- May was an active member in the secret BBMP, which she and her colleagues concealed from the public for over two decades.

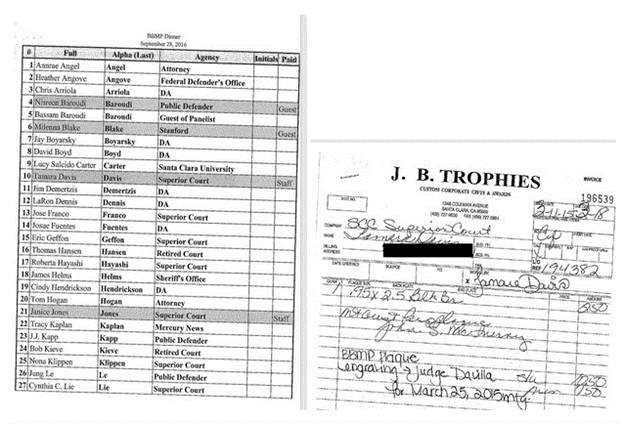

As previously reported by the Vanguard, the BBMP was a group of judges, private attorneys, government lawyers, police officers, politicians and reporters who met in secret off record meetings on the public dime. The BBMP was exposed in the Vanguard’s Tainted Trials, Tarnished Headlines, Stolen Justice series.

San Francisco Superior Court Judge Roger Piquet recently appointed Jacob- May as a mediator in a lawsuit filed by now deceased Senator Dianne Feinstein against her late husband’s estate. Katherine Feinstein, the daughter of the late Richard Blum and Dianne Feinstein, was given the power of attorney in that matter. According to local news reports, she has alleged the trustees managing her father’s estate failed to pay her mother’s medical bills and have engaged in elder financial abuse, according to news reports.

Secret Judge Club Produced No Photos or Recordings

The Vanguard has reported extensively on the Santa Clara County secret judge committee, BBMP. Unlike the committee formed and supervised by former Chief Justice Ronald George, the BBMP was not publicly noticed, kept no public record of meetings, invited only select police officers, politicians, private and government attorneys. It also created a culture of conflicts that seemingly influenced legal outcomes, media coverage and elections relevant to local Silicon Valley government and costly political campaigns.

The few records kept by the underground BBMP judge group show what judges and other BBMP members ate for dinner, and how it was paid for. However, the court allowed the operation of the BBMP for nearly forty years without public oversight. The secret BBMP judge group created and maintained a culture similar to what was seen in police culture, before the implementation of BWC.

Judges Locking the Public Out of Public Courtrooms

As early as 2020, court watchers began to investigate remote access to family and criminal court proceedings throughout the state. BBMP member judges Vanessa Zecher, Jessica Delgado, Andrea Flint, and Cindy Hendrickson, reportedly left court watchers circling in virtual waiting rooms for hours in a manner that felt selective and arbitrary.

Self- represented litigants, who were not informed of conflicts of interests local judges had with local attorneys through the BBMP, were often blocked from accessing remote public hearings, then blamed for not being present in court.

Local lawyers who had attended secret BBMP meetings, local bar events, judge nights or were associated with local judges through membership in the Inns of Court, seemingly were allowed to miss appearing remotely, or in- person, and treated favorably by BBMP judges when their absence resulted in a hearing being continued.

After the Vanguard saw similar issues in other counties, an inquiry was made to court administrators, who largely refused to comment. However, Santa Clara County court attorney and longtime BBMP member, Lisa Herrick, stated judges have discretion as to who to provide remote access to for their courtroom’s public hearings.

Media Requests Find Judges Not Following the Law

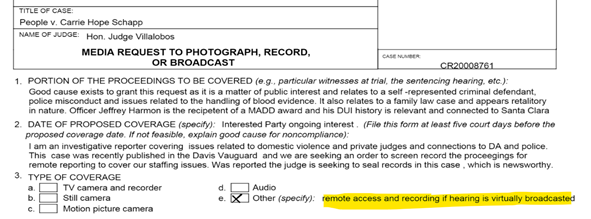

The Vanguard also made media requests to test remote access to public proceedings in Stanislaus County , where remote access was requested as well as an order to record the public proceedings, remotely. The court has allowed Google to record in courtrooms and broadcast on YouTube in the public domain yet continues to assert judges can control how recordings may be taken and used. Judge Ruben Villalobos, the judge assigned to the case, held a hearing on the request, and excluded the Vanguard from the hearing, then denied the request.

In Santa Clara County, the Vanguard requested remote access to family court proceedings. Judges Delgado, Zecher, Hendrickson and Flint failed to provide notice to the parties that a media request had been made in the case.

In Kern County, Judge Schuette failed to provide notice to the parties that media request had been made, and additionally failed to file the request, as the law requires.

In Los Angeles County, the Vanguard recently made a media request in a domestic violence case with mutual orders. In that case, controversial divorce attorney Dennis Wasser and his wealthy client wanted to sell the family home, evicting a former wife and young children, in order to pay Wasser’s attorneys fees from community property. Judge Mark Juhas who was recently given an award by the Judicial Council and the California Lawyers Association, never informed the parties the request had been made nor ruled on the request as the law requires.

Cameras in courtrooms would allow the public to see if judges are following the law when it comes to media requests and requests for remote access to public hearings.

Costs for Cameras and Remote Access to Public Court Proceedings

In 2004, California voters sent a strong message to public officials when 83.1 percent of voters voted to include California’s Public Records Act in the state’s constitution. However, since that time, judges in the state have historically sought to obstruct cameras in courtrooms which denies the public access and transparency over court proceedings.

A public records request to Orange County and Santa Clara Superior Courts recently revealed how much public investment has been made in technology including Zoom, Dell, and Microsoft to provide cameras and remote access to the state’s public proceedings, which the Vanguard is evaluating.

A flip of the switch and the state could put cameras in courtrooms. If that were done, parties would be able to appear in hearings remotely and could additionally save money by having written records of proceedings produced by private businesses. Legal consumers and court users could use outside businesses and technology to document public court proceedings, rather be compelled to use overpriced court reporters who are allowed to own the copyright on a transcript and charge obscene fees that average $500- 2000 for an hour for in-person public court hearings.

Taxpayers have already made the investment to put cameras in courtrooms. The public wants cameras in courtrooms and only judges are continuing to draw out the fight to keep them out.