Freedom Reads: The Books That Liberate

Reginald Dwayne Betts is a poet, lawyer and the Founder and CEO of Freedom Reads, a Mellon Foundation-funded initiative formed out of the Yale Law School’s Justice Collaboratory that radically transforms the access to literature in prisons. For more than twenty years, he has used his poetry and essays to explore the world of prison and the effects of violence and incarceration on American society.

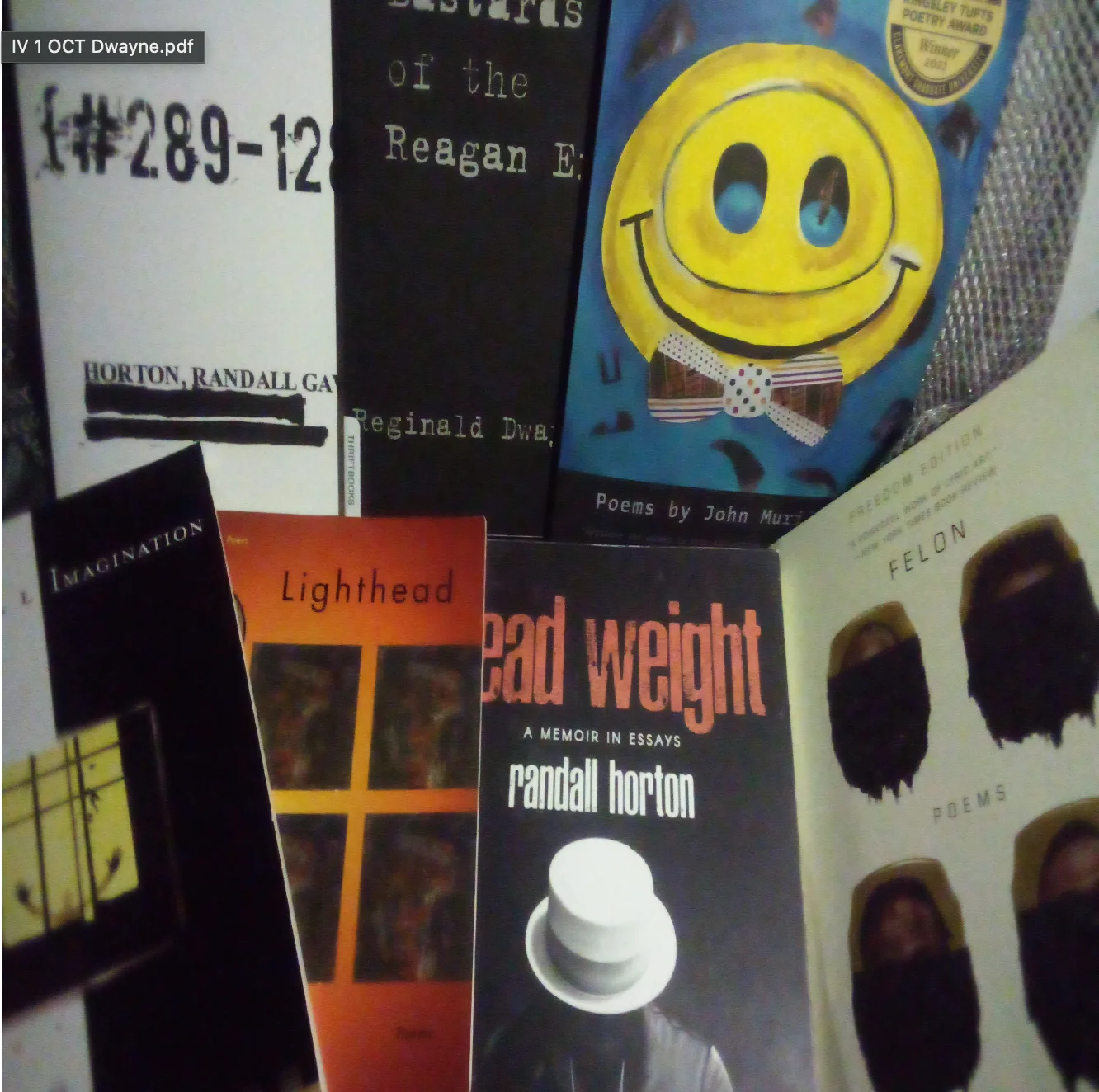

The author of a memoir and four collections of poetry, including the American Book Award-winning Felon, Betts installs curated Freedom Libraries throughout the nation’s carceral state. In 2019, he won the National Magazine Award in the Essays and Criticism category for his NY Times Magazine essay “Getting Out,” which chronicles his journey from prison to becoming a licensed attorney. A 2021 MacArthur Fellow, Betts has also been awarded a Radcliffe Fellowship from Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute of Advanced Study, a Guggenheim Fellowship, an Emerson Fellow at New America and most recently a Civil Society Fellow at Aspen.

Betts holds a J.D. from Yale Law School. His latest book, Redaction, co-authored with Titus Kaphar, was published in 2023. Betts advises the nonprofit Ben Free Project board of directors.

If you’re reading this while surviving confinement somewhere within the carceral state leviathan, take a moment to inspect your institutional surroundings and hunt for evidence of those scarce but powerful levers of enabling agency capable of fueling the viability of your becoming. Ponder your becoming. Really survey your surroundings for tools that might enable you to transcend the place they call prison.

Give attention to those spaces, services and experiences that didn’t come shrink-wrapped from the DOC in a who cares what you need one-size-fits-all fashion, but instead are those curated off-menu blessings that have been expertly gifted and positioned for your use by sages who have stood for count, emerged from the tomb of civil death and double-backed to populate your cellscape with life-altering value.

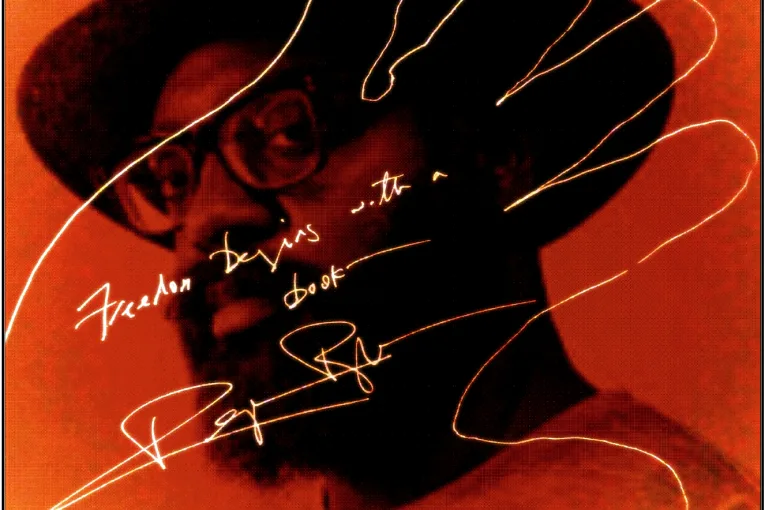

Through this lens, few folks on the planet are contributing more than lawyer, poet and carceral literacy activist Reginald “Call Me Dwayne” Betts. His Freedom Libraries are planting academies in the darkest of gardens. Consider this an ode to the gardener – this is about gratitude.

Describing the work his nonprofit Freedom Reads is doing to reset how confined readers gain access to solid literature, Dwayne told us, “This started with a 5.25 million dollar grant from the Mellon Foundation. Though, truth be told, this started years earlier, with some early initiatives where I sought to get the country’s best and brightest writers to put pen to paper about issues of and around incarceration.” In fact, Mellon’s 125 million dollar annualized Imagining Freedom arts and humanities grant program has served to amplify the Million Books Project mission that Dwayne first leaned into with the help of Yale Law School’s Justice Collaboratory.

Sentenced to nine years in a Virginia adult prison for a confessed car-jacking he committed at the age of sixteen, Dwayne has said “books became my sanctuary and refuge. And they were with me, from Faulkner to Shakespeare to Walter Mosley and Toni Morrison and Ice Berg Slim, for my entire bid.” Echoing the redemptive power of literature, he ruminated on how although “we all understand how our lives can be ruined by prison and violence,” too few understand how “books can rebuild some of that.” These are not the vapid platitudes of a grant-chasing ex-con. Dwayne lives it.

For the first five years of his term Dwayne didn’t have access to DOC-procured literature – because “there wasn’t a library.” Five years without a prison library. Chew on that. His societal reentry exemplified the criticality of books for his personal rebuilding when, while working at Karibu Books, the independent African American bookstore that gave him his first job fresh out of prison, he formed the YoungMenRead book club for Black youth between the ages of six to seventeen. A full fifteen years before founding the Freedom Reads nonprofit organization in 2020, before he’d ever published anything, Dwayne was a community college honors student standing in the literacy gap – with a book in his hand – serving others.

As he wrote in his 2019 American Magazine Award-winning essay “Getting Out” for the New York Times Magazine (NYTM), “Before my thirtieth birthday I’d earned a bachelor’s degree and an MFA in poetry; published A Question of Freedom, a memoir about my time in prison; published a collection of poetry, Shahid Reads His Own Palm; and still knew my state number by heart.” Dwayne’s literary work rate while attending college was so prolific, he seemed to have shoved ten years worth of productivity into five. He was exploding with intentionality.

However, when Dwayne finally came to California and visited us at Valley State Prison (VSP) in early 2023 to install libraries, perform live and take questions, he confessed about how despite winning in back to back years the Beatrice Hawley Award for his atoning memoir and the NAACP Image Award for nonfiction for his poetry debut, after earning his MFA he couldn’t secure for himself a teaching gig – like, anywhere in the nation. Dwayne couldn’t even secure an interview. He was shook. Call a felony gravity and it will answer you with a dragon’s shackle, ball-and-chain style. #grounded.

Many of his unpublished academic MFA peers without a felony jacket secured interviews and job offers. After shaking the tree in the Washington area he expanded his search nationwide, only to find a series of unopened doors. A lesser man would have developed a serious chip, but Dwayne was too “gravid with fear,” rooted in his role as a father and provider. With student loan debt lurking in the corner, Dwayne worried he might “never be gainfully employed, able to pay the rent, or purchase diapers.” The cold world J. Cole spits about felt especially chilly to Dwayne – it was icing him out.

We won’t soon forget the angst in his face as he stood in our visiting room and told this story more than a decade removed from that season of rejection. You’d have thought it was yesterday. The same pained look accompanied his quite complex and tender description of his relationship with his father and remained fixed throughout his live performance of several slivers cleaved from his American Book Award-winning work Felon. His telling added a layer of vulnerability to what had appeared to be a storybook tale of reclamation. It made dudes empathize with Dwayne. He became relatable in a way his literary awards and Ivy league pedigree didn’t necessarily permit.

It was the sort of biographical factoid that most incarcerated fans of Dwayne’s poetry wouldn’t have had knowledge of otherwise because he had only written about it in a NYTM essay, which we can’t access on EBSCO using our college program laptops. We only got to read Dwayne’s essay because it was featured in the paperback version of The 2019 Best American Magazine Writing, which only came our way at all because it lives within the Freedom Library. Being stuck behind the digital firewall kept a major life obstacle arc in Dwayne’s story missing from our view of him until long after we’d become fans of his art.

The back and forth time travel journey that is the praxis of reflectively moving in and out of experiences past using poetry as the medium, exercises the endocrine system by dancing between modest exposures and a full flooding. A very real operant conditioning must be happening in Dwayne – in a most uniquely cathartic and transformative way – as he repeatedly enters and exits our nation’s prisons. Someone as observant and self-aware as he is likely doesn’t have a problem identifying the story he is in – it’s usually a question of sufficient bandwidth allowing its synthesis without derailing the train. Because Dwayne’s experience presents as a unicorn-like singularity, we’ve always believed that in order for his story to truly shift a young incarcerated non-reader toward literature, it must be both ontologically digestible and emotionally accessible for them to connect with and be inspired by.

We marveled at how, though being fully annointed as being nice with the poems and regarded as a bonafide literary beast, Dwayne still possessed the capacity for reflective self-deprecation. His sobering tales of occupational woe left many guys jaded about their own life prospects, with some thinking: man, if his two award-winning books, four degrees and the prestige of being a Yale law grad wasn’t enough to etch-a-sketch a teenaged crime that didn’t kill anybody into a clean slate, then we all are f–ked. Though an oversimplification of Dwayne’s circumstance, we can’t even count how many times a similar refrain has been jousted against the hope that lives just above the systemic paralysis some succumb to while wrestling with possibility behind the wall. Trauma is real.

Then again, triumph trumps obstacles everytime. Dwayne is the living and breathing example of uber possibility that all incarcerated folks can inhale, even if his achievements are out of reach for most. “If who I am today matters more… than the crime that I committed in 1996,” Dwayne has said, “then we can have a conversation about the things that got me here and how to get other people to versions of here.” He is keenly aware of his apex achiever status. Our awareness contends with how intimidating a book can be for those who can’t pronounce the words or comprehend the genius waiting to be discovered in the Freedom Library. We are consumed with connecting our peers to the books that hold the medicine.

As for the stiff-arm Dwayne experienced while looking for teaching work, it sounded a lot like what two-time American Book Award-winning poet Randall Horton encountered at Central State University after having received what Dwayne had not – a job offer backed by a signed contract. As he wrote in his memoir Dead Weight, while holding his Ph.D. in one hand and seven felonies in the other, Randall was offered a Distinguished Scholar-in-Resident post by the HBCU’s English department chair, only to have the school’s provost rescind the offer after the contract had been signed. The provost refused to allow the HBCU’s reputation to be stained by the hiring of an ex-con. Merit and academic qualification were never part of their calculus. Michelle Jones experienced a similar take-back by Harvard as a Ph.D. candidate.

In Dwayne’s case, we imagined a cabal of hinky whisperers swapping ‘concerns’ about what kind of damage being thrust into an adult prison at sixteen and spending eight years in that setting might have ‘done’ to this guy – feigning concern for him while masking the true motive. Code for: Is he still dangerous? Are we rewarding criminality? Should we hire an ex-con? Will his presence diminish our faculty’s credibility? Will our funders support it? The real: He will forever represent the pistol-waving visual of a young Black male terrorizing an innocent motorist. Jackal versus civilian. Street urchin stalking a square. #superpredator

A voicemail from the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study offering a fellowship at Harvard University gave Dwayne the equivalent of a job and bought him some time just when he really needed both, allowing him to grind on his second book of poems, Bastards of the Reagan Era – our fav, full disclosure. When they ran out, Dwayne still couldn’t find teaching work. The prospect of law school became a sort of life plan bouey. He told our audience that the decision to even go to law school at all was as much a financial survival math movida as it was a capstone intellectual ambition. Brutal honesty. Pretty brave too; after all, this is a dude who plowed through the rigor of law school not knowing if he’d ever actually be permitted to practice law at all, owing to the state Bar Examining Committee’s character and fitness review authority.

Dwayne, the poetry cat with two Pushcart Prizes and a few books under his belt who couldn’t get an interview for an English teaching job opportunity while holding an MFA, would become accepted into every top tier law school he applied to, where the mastery of language, logic and argumentation was a most definitively dispositive undertaking. Dwayne opted to attend the place most SCOTUS justices are trained – Yale Law School. Merit finally prevailed. Ironically though, Yale would refuse admission to Jones.

We’ve never hit Dwayne up about why he didn’t decide to go teach English after Felon’s critical success while armed with his Yale pedigree. He could have easily claimed a lay-up tenure and taught English from the ramparts of any bricked university he wished. We didn’t ask him how come he wasn’t holding it down teaching law either from one of those enclaves that no doubt would absolutely love to tout his accolades and virtue signal his hiring. We figured that the answers to those questions were not mysteries at all, but perhaps rather obvious to anyone paying attention to the underlying vibrations driving Dwayne’s motivation.

Our theory of the case:

The books keep him pushing into prisons, navigating through them and walking out – elevating the spirits of readers, shedding a small layer of his own unique trauma accumulation each time and centering himself during the flight back to the C. A healthy cycle of exposure and renewal keeps Dwayne tethered to the experience that shaped his becoming and gives him an endless series of release dates and homecomings.

As for the lawyering, that’s reserved for the homecomings he works to affectuate within the parole hearing matrix for his real ones who remain on the shelf. Until they are out and traveling and doing prison installs with him, nothing changes. The gardening work must continue.

Sadly, having his post-MFA bids for employment shunned by colleges and private schools around the country wasn’t the first time Dwayne had to suffer the indignity of being ignored by invisible gatekeepers because of a teenage mistake he wrote “would forever be a hellhound.” The hallmarks of youth determinations made by the USSC concerning LWOP sentences for minors tied to science about how brain development imputes mitigation to the culpability calculus for youth offenders whose brains haven’t fully formed didn’t translate into opportunity for Dwayne as he tried to climb the academic ladder following his graduation from Prince George’s Community College as an Honors Academy scholar three years earlier. When he applied to Howard University for a scholarship, the HBCU stiff-armed him Ban The Box-style.

Dwayne disclosed his felony on his scholarship application and when he did, the acclaimed HBCU never acknowledged his application thereafter. His academic honors scholarship application, which he lodged in person, suspiciously disappeared without a formal decision issued. To us it smacked of the same we did it but you can’t prove it way race-based exclusionary housing practices of old involved trashing the rent and mortgage applications from people of color sans interview. Interestingly, it was Howard that also refused Randall’s attempt to re-enroll as an undergrad after he exited prison, ignoring the fact he’d previously been a student in good standing there before dropping out.

The HBCU’s seemed determined to keep all the felons from passing through the gate. “I fully respect their right to decide who they want to award scholarships to and believe that my waving a pistol around in people’s faces as a child carries heavy consequences, some of which I paid while inside and some of which I pay still. But when I talk about Howard it’s to highlight a few things,” Dwayne said.

He’d earned it; and yet, Dwayne’s static and immutable past had been misused to shut him out based upon something other than his exceptional academic aptitude, the same way static case factors are deemed aggravating in parole board hearings, though they objectively are not. It’s really an indictment of the learning institution’s feigned belief in the power of the liberal arts education it offers – a sort of tell or confession revealing something purely transactional. Princeton, Yale, Harvard and Cornell offer courses to imprisoned learners, so what is really up with the HBCUs? Randall questioned why places like Howard and Central State adopted the “philosophies of the protagonist in Invisible Man had to endure at the mythical HBCU in Ellison’s novel” that “mimicked the mentality of the oppressor to further oppress those who blindly subscribe to operating within the white gaze.”

If a college won’t admit a student or hire a teacher who has excelled after the felonious chapter of their life based solely on the social stigma bias of their felony record, then that school can’t truly claim fielty to all the same selling-point reasons it gives to the paying students it courts when imputing to its academic product and the diversity of its campus culture the full-scope formation impact it claims will result in the student becoming a supposedly well-rounded world citizen by virtue of attending there. If college life does have the capacity to perfect a person’s character and integrate students into a community of service, then any school that discriminates on the basis of a felony record necessarily disavows the claim that its own product can improve a person, admits it is merely a transactional business and forfeits the humanitarian veil.

Felons are bad for business – unless of course, they come armed with a Pell grant. It’s a crooked math.

To us, this just reeked of the raw survival politics rooted in what must have been a constant refrain from boosters and administrators at the school – and perhaps HBCU’s writ large – consumed with the strain of avoiding the sorts of self-inflicted reputational vulnerabilities seemingly made more visible and more likely by positioning a weapon-toting Black felon just two years removed from prison as the school’s scholarship poster-child. There was no room for Dwayne’s redemption, be he the ascending scholarship student or the credentialed professorial candidate.

“One, this wasn’t an institutional decision,” Dwayne explained. “It was one or a small group of employees deciding that it wasn’t in their best interest to make sure I received the scholarship that I’d earned and been awarded vis-à-vis being a member of a local community college program that carried with it a full tuition scholarship to Howard.”

Dwayne handles the rearview critiques of those who might have failed him with a poised and calculated deftness that eyes the utility of reshaping foes into allies who might bend toward the arc of righteousness and prove nevertheless to be future collaborators. A long view aided by refined high-bar emotional regulation tools and polished people skills are vital when courting funders, engaging the nation’s prison wardens and chopping it up with a different population of confined readers around the country each week. Dwayne’s capacity for swallowing down what might trigger another, in the interest of what might be possible down the road, is a testament to his patience and bridge-building acumen.

Dwayne can afford to be magnanimous, but the fact that this supposed small group of employees might have held control of Howard’s scholarship purse doesn’t account for why his application denial was never communicated to him as is done in the normal course of such processes. That Dwayne’s application wasn’t deep-sixed, but perhaps just mistakenly ignored for reasons having nothing to do with his felony record, to us, seems about as plausible as there not having been a viable radio traffic recording of the Secret Service’s protective detail assigned to protect Donald Trump from the assassination attempt that nearly murked him in bloody living color in Butler. There needs to be accountability in each instance.

“The second point is a bit more complicated – I want the institution and those of us who support such institutions to push them to do better in the future, to articulate what it means to do better, and to acknowledge that what happened was foul.” He said the quiet part out loud. It was foul – but Dwayne sucked it up, took the L from Howard and caught a tuition-free full ride to the University of Maryland instead. Jay Z’s lyric, “They put themselves in the air, I just kick away the chair,” epitomizes the alumni suicide Howard committed when it disavowed Dwayne. Bad bet y’all.

For Howard, it didn’t matter that Dwayne was Black, academically uber-qualified and had already turned his life around, evinced by his public service community action work around books. All that mattered were the optics of his felony record. Instead of helping a disenfranchised learner of color like Dwayne and becoming forever bound to the trajectory of his genius, Howard became a gargoyle mascot for the sort of barrier to higher education and the development of Black academic excellence its HBCU charter proposes to dismantle. Howard is now the sour HBCU footnote of hypocrisy beneath Dwayne’s epic story of redemption, as well as Randall’s. We said that – they didn’t.

For a Black honor student working in an African American bookstore and running a book club for Black teens, the appeal of attending Howard must’ve seemed pretty instinctive. It would’ve been a storybook turn, fo-real. We’ve sulked on his behalf. Though he did permit us to prompt him to engage a subject he has only devoted a few sentences to in print, Dwayne is too composed to tear Howard apart publicly and give the episode too much oxygen. Less is more. Besides, Dwayne’s two NAACP Image Awards have since effectively rebuked Howard’s early rejection of him and served to honor the cultural significance of the very work Howard sadly couldn’t imagine a felon transfer student was capable of – twice. Take that.

As the caretaker of a multi-million dollar Mellon warchest, Dwayne is appropriately cagey about complaining in public forums, even when standing on the moral high ground. “I don’t want to be upset over the failures because I’m trying to be obsessed over freedom. I’m not trying to spend my life arguing with people about why we weren’t and aren’t superpredators. I want to spend it proving the lie to the statement and supporting others doing the same thing.” As incarcerated creators operating at the edge of potential, we enjoy no such flexibility, though it is telling that Dwayne agreed to dare touch these subjects at all, let alone do so with the likes of us. It’s just another example of Dwayne selflessly leveraging his life in service of our modest journalistic ambitions.

The academic and occupational obstacles Dwayne faced were similarly rooted in a university ecosystem that is now, ironically, being flooded with federal Pell money it hasn’t seen since the mid-90s and waves of formerly incarcerated students and faculty members teaching all across the country. Benjamin Frandsen, a former California life prisoner, is now a teaching assistant in the MFA program at California State University, San Diego – he received the sort of job offer Dwayne did not, pre-MFA. These are the overcoming obstacles and everyday injustice narratives we have always thought needed to occupy a more so-centered and amplified position in Dwayne’s messaging. As one of our workshop participants points out, Dwayne should voice his saga using his Freedom Takes podcast, so that confined users of DOC-issued tablet devices can hear the “Getting Out” essay, audiobook-style.

This request came direct from a young poet Dwayne met at VSP who will parole soon:

Aye yo, Dwayne, thank you for the books and energy. On behalf of all the young cats and old heads around the country who haven’t read your essay yet, please consider taking a beat, grabbing your phone, reading your coming of age story aloud and posting the audio of that joint on Edovo. Make your story as accessible as possible, as soon as possible and do so as easily as is now possible using the digital platform that confined people can access for free – where your Freedom Takes podcast is already available. Make your reading of the essay an episode big bro.

Please don’t allow the carceral resident consumption of the most inspiring and eloquent post-carceral BIPOC ethnograph to remain ethereally unknowable until you visit each of the over 400 spots throughout the country where Edovo is available for free on these DOC-issued tablets and they get it in paperback. Folks need to identify with you long before you truck books onto their yard – like our Barz crew did. We found your essay to be endearing, brave and worthy of a movie – when we finally got access to it. We want our peers around the country to learn about you the way you chose to frame your journey from prisoner to lawyer, tonight! Anybody who reads or hears that, will salute your life and stand in the literacy gap. Bet. ~ Torrey “Skrybe” Thomas

Because he relies on the cooperation of the prisons he enters, Dwayne is mindful about his tone and manages his messaging responsibly. However, as stakeholders who preach his life to new readers in prison in order to encourage them to imprint upon Dwayne’s transformation within workshop settings, we have seen firsthand how folks increasingly identify with Dwayne – and poetry – after having heard about the unjust obstacles he’s faced and overcome. Be it five of eight years without a library, an academic scholarship withheld, a job interview refused, or having to run the hamster-wheel awaiting Bar approval, there is a powerful driver of motivation and identity living in the exposition of Dwayne’s success when contrasted against these injustices. It really needs to be harnessed and wielded on the front end of Dwayne’s outreach efforts using all the tools in order to maximize the imprint potential.

Story being the hook, we thought Dwayne’s story needed a fuller telling – better said, it needed an earlier telling. The young cats who love rap music but don’t read are the stakeholders we are most concerned about. In our view, they needed to identify with who Dwayne was at sixteen and then find a connection to his disenfranchisement as he sought to reinvent himself. You see, we are literacy activists on the ground where we live, so our daily exercise is the uprooting of bad scripts. We needed Dwayne’s life to be actively inspiring, not implausibly unattainable. Yale means nothing to someone who scoffs at the prospect of passing the GED exam while the DOC offers him a six month sentence reduction if he passes. Did you catch that? Let us repeat it. When six months of freedom isn’t enough to incentivise someone to read, a Yale backstory does us no good. Finding the right motivation button to push in a young society dropout is everything.

To do that, we needed to know about and lead with the worst parts of the early struggles that Dwayne doesn’t necessarily still center and harp on from his current altitude. He has moved beyond his own narrative; yet, in a real way, we have intentionally seized upon those early ingredients that won’t make Dwayne any new philanthropic friends, but will cause our hardest cases to identify with him just enough to let us hit them with his coldest heat rock verses. If they can relate to him, they will sniff his art. Like Skrybe, we have seen dudes gravitate to Dwayne’s life based upon how we present him for the first time. With our younger residents, starting with his achievements has never worked as well as starting with his failures and obstacles. Injustice has a universal appeal.

Putting his “Getting Out” essay front and center has always proven to be more powerful than his poetry – particularly with young BIPOC gang members who don’t read, hate school, love drill rap and think poems that don’t rhyme are ready-to-be-clowned examples of “bad barz.” Rap culture marginalizes MFA poetry in the eyes of young non-readers in prison – it’s a thing. So, when we do jump into his poetry, we don’t even start with Felon, because that work is too introspectively resolved. Bastards is that big brother primer that lives closest to their street POV deconstructing the wages of vice and diagnosing the perils of the culture. Felon is aspirational – it’s an old head looking back on his life after he’s left the street. They are chapters.

Having met Dwayne and chopped it up with him via phone and text, there is no denying the respect and humanity with which he engages vulnerable folks who lack agency and can’t offer him anything – those they refer to still as prisoners. We can attest to the many shades of his personality that interrogate ideas, invite contribution, probe possibility and offer real collaboration with people like us who fist fight fire many rungs below him on life’s ladder without lording his accomplishments over us. He has allowed us to wield his life in order to try to save the lives of others here who haven’t yet fallen in love with books.

“The best thing y’all have ever done is to keep calling me,” he once told us over the phone. He treats everyone on the inside with dignity. He answers our emails. He keeps pressing 5.

Dwayne’s presence is everywhere. The books are squatting in our day room. His articles swim in our EBSCO database installed on our college laptops. His Freedom Takes podcast is available on our DOC-issued tablets via the Edovo app and he’s speaking to us via PEN’s The SentencesThat Create Us writing guide. One of the most direct-action comms to come from Dwayne was his “How I Became A Prison Poet – And So Much More” interview with PJPxINSIDE, wherein he described how incarcerated writers should “start by noticing anything well, and you move from noticing well to describing well, and then you find these moments where you glean insight and wisdom from what you describe.” Mentor gold.

Dwayne then said something that we found especially inspiring that is largely responsible for the audacity of our journalism pursuits. “It would be great for incarcerated people to develop healthy chops, and extend those chops out into the world… Writing reviews for the New York Times Book Review and for literary, academic and legal journals.” Nearly a decade after Dwayne wrote “The Stoop isn’t the Jungle” for Slate while attending Yale, we published “Gladiator School” in Slate – from prison, with an assist from College Inside’s Charlotte West. We then became invited by the editors of the Journal of Prison Education Research at Virginia Commonwealth University to present a first-of-its-kind practitioner paper describing our teaching artist perspective as facilitators of the Barz poetry workshop that uses books from the Freedom Library. We started scoring small victories of agency by positioning our witness accounts into the public sphere.

Dwayne’s call to normalize the participation of incarcerated writers in public-facing spaces echoes pieces of Gwendolyn Brooks’ summons issued via her “To Prisoners” poem. When a writer of noble stature reaches into the belly of the beast to advocate for marginalized creators, as Gwendolyn did for Etheridge Knight, we must meet that leverage with work that can exist without training wheels. Having nothing but what we have already read to lean upon – sans MFA training – ours is a sink or swim proposition, with everyone’s eyes upon us. We reflexively knew the answer to the question Harvard’s Elisa New asked Dwayne about regarding Gwendolyn’s use of “chalk” for her Poetry Foundation-backed To Prisoners special – as would any 80s baby from the Reagan era who has seen a crime scene after the body has been scraped and bagged into the meat wagon.

In the tradition of Brooks’ activism, Dwayne made books the free commissary items for all of us. Knowing that his prior Freedom Library installations around the nation, including at places like Angola, had only contemplated a single micro-library unit situated within the prison’s existing facility library, traveling to VSP represented Freedom Reads’ first trip to California. It was also his organization’s largest mass installation to date, delivering eighteen units filled with 9,000 books valued at nearly $240,000 to a single prison. We wanted to know why us – what made him decide to go so big here?

“This is a difficult question,” he conceded. “On some level, we come where we are called. And so Brantley Choate, the Director of CDCR’s Division of Rehabilitative Programs (DRP), believed that VSP should be the first spot in California. And when he talked about the work guys like your crew are doing there, that mentoring and educating work, I knew this is where we needed to build libraries. Because, the truth is, we’re just the first step – the hope is that folks like you will bring the library to life by doing work around it – poetry readings, writing workshops, making it a gathering space akin to the television during the Super Bowl.”

VSP trains and employs residents as certified Substance Use Disorder counselors, Peer Support Specialists, Peer Health Educators, Youth Offender Mentors and has resident teaching artist practitioners facilitating literary and performing arts-based self-care modalities like Barz Behind Bars that onboard trauma-informed community forming programs designed by stakeholders.

“Those are things that we need people to do and further our model,” Dwayne emphasized. “But beyond that, when I had a chance to Zoom with y’all, I knew this was the move. And then bringing eighteen libraries to one prison, spending a day unboxing books, the vibe was apparent all across the compound – we were doing something that matters while knowing it was the start of it all and not an ending.”

A trove of Black voices sustained Dwayne while confined. He didn’t emerge an angry man raging against invisible foes and blaming the prison industrial complex for being the cause of his detour. Dwayne slid off the top bunk broadly steeped in the classical canon, clear-eyed about his personal culpability, ashamed of his conduct, distanced from his father and appropriately cognizant of the moving parts assembled to convey him into his becoming. His capacity for ownership was the stuff of a bold-ass philosopher twice his age. It’s all there in Bastards. We can see him time-capsuling and reporting like a back-pack rapper on the condition of his own teen era while diagnosing a former life since vacated. He was finding his voice by pushing the pen about a lost generation. He’d become long before he started telling the world about it.

Dwayne exited confinement remarkably transcendent. More than a word nerd, he’d developed into a self-taught, against-the-grain free thinker who wasn’t falling for the easily-pimped liberal talking points that blame-gamed something – anything – other than the pistol he swung. He wasn’t making layered esoteric excuses for what he’d done. He wasn’t accepting anyone’s custom-made cop-out either. Instead, he fashioned a moral compass formed from wood – paper, and got to speed-reading. Slavery aside, like Abraham Lincoln, Dwayne taught himself how to chase down and extract from books everything he needed in order to evolve. He taught us journalism by using his nonfiction narrative – with no cut.

What Dwayne has become within the spheres of post-carceral academic success, literary achievement and public service represents a hydra of transformational self-discovery, cultural mentorship and tireless humanitarianism unmatched by any other human to have emerged from captivity as a youth offender in the past century. Consult a fact checker. We’ll wait. Few had less to work with for a longer duration of confinement as a teen. Nobody has exited prison and ascended both the academic and literary ladders faster and with greater success. Nobody has put more literature into the hands of more people in prison, or will. Few have reached down farther to pull more writers into the light – ask John L. Lennon. He is in a league of his own. We see him. He deserves your attention too.

His testimony, his works and his travels into society’s most unwelcoming places to serve those who can’t do anything for him is as praiseworthy as his personal relational journey as a son, husband, father, writing mentor and parole attorney. He excavated and artistically conveyed his own life’s bruises, unabashedly, in order to acquire the philanthropic resources to help others trapped in the carceral state. His impact forms as a volcano of selflessness. We sometimes wonder if he knows just how meaningful his contribution has been. It might likely seem to him at times as if our arms are reaching out at him zombie-like and hunting his influence. In fact, it’s really more of a solidarity-dap/bro-hug laced with sincere gratitude, morphing as an interview, riffing like a profile and swerving into the crevices of a man who has altered our lives.

This is simply us noticing anything (Dwayne), as well as we have been able, and gleaning insights from what he has allowed us to observe. It all gets deconstructed into the particulars that flush out carceral life using twenty six letters.

Take prison barbers for instance – they represent a unique cast of skilled artists whose prison job actually prepares them well for the real-world demands of their vocation. Wielding an Andis clipper is precisely the kind of entrepreneurial labor an old-head lifer or young boy should be able to parlay into a chair situated in any corner of humanity when they slide out. Somebody in Gaza is getting a taper fade as you read this. In California, you can’t even get a pedestrian barber’s license with a felony absent a Governor’s Certification

of Rehabilitation, which is nearly the equivalent of a commutation or pardon action. The state’s Barber and Cosmetology vocational training programs offered in our prisons amount to nothing more than a pro forma exercise in reentry futility. Writers have a duty to witness for those who don’t.

Cash bail, extended parole tails, sentencing enhancements and the unavailability of higher education in prisons are systemic viruses we all can agree become weapons formed against those without means, effective representation, or luck. The reach of punitive measures extends beyond the cell door. That said, when a first-termer serves out every day of his bid, completes the entirety of his parole and has paid his restitution in full, if rehabilitation is the objective, we think his felony should be wiped for the purposes of civic reintegration. Time served = clean slate.

Dwayne opined that, “We should have a far more robust use of the pardon power. We also need to eradicate some of these senseless collateral consequences. Though, maybe saying collateral consequences is also a bit of a euphemism — these are the consequences and we have to keep making the case that they are not legitimate.” Making that case means centering egregious examples of injustice alongside power abuses in the same manner Dwayne embedded Rodney within “Crimson,” alongside Juvie. It also means our nation’s Presidents (we’re talking to you Barack Obama, Joseph Biden and Donald Trump – dare we type Kamala’s name?), using their pardon powers to remove the dead weight from men like Dwayne – without him having to grovel for it, ya dig? He’s earned it. #MedalOfFreedom

Having seen the contemporary Black version of Faces of Death – police snuff flicks – enough times to now nightmare routinely about Garner and Floyd in the same way that grainy Simi Valley camcorder footage etched a most vile brutality into our younger menus, there has to be attention paid to the many less-than-deadly indignities that creep up on a generation like warmth before the boil. We’re all frogs. It’s up to the artists to continue to identify, articulate and bullhorn the stench of the present age. After confession, must come duty. That is the mandate. Perhaps one day we’ll get to play editor and present the curated fruits of our workshop’s labor in a carceral rhyme book anthology that says gracias to Dwayne properly. We’re eyeing those shelves, best believe.

From where we sit, Dwayne has used his life to shape his art in order to then have his art become activism that reshapes the malformed spaces that underserve so many while shelved away. It’s pretty damn poetic. He is directly reshaping the space he experienced by inserting the things he never really had access to on the inside. He also employs formerly incarcerated folks. We tip our caps to Elizabeth Alexander and the folks at Mellon who chose to fund Dwayne as an instrument to be wielded within the carceral state. We are actively engaged in the type of agency literature can enable, largely because of him.

Lifers read more than most humans. We devour media because it’s so scarce. We sit in more rooms with more visiting speakers, academics and life-coach types than likely any other segment of the free world population outside of church and Alcoholics Anonymous folks. We’ve seen and heard it all, but we pursued Dwayne with a naked intention to build something that seeks to harness the Freedom Library and give its users broader experiential agency in order to innovate new verticals of meaning.

The density of our comms, reflective of our urge to implement what we know can transform how literature might move through our population, has tattooed our digital volleys with Dwayne since day one. “Truth be told, it’s a bit of a duty to respond,” admitted Dwayne. “Y’all do send lengthy letters – but it’s always filled with ambition and possibility. I think about the mission of Freedom Reads and it’s not just about building libraries. It’s about providing the kind of support for people like you doing this work that was missing when I was inside.”

True to his word, Dwayne leaned into an interview request of ours along with Randall, who serves as a Freedom Reads Literary Ambassador. That conversation appeared in an excerpted form within Columbia University’s School of the Arts’ annual literary magazine Exchange, representing a sort of categorical first for carceral interview journalism therein. By getting down with us in this way, Dwayne allowed himself to be the content bait that made our work worth publishing at all. His generosity was especially selfless in that he took the time to articulate his answers while plane-hopping through a press run for Redacted, his latest book of poetry he shares with the artist and filmmaker Titus Kapher.

Discussing the power of literature and the arts, Dwayne talked about how, “We all know that writing is that thing, the arts is that thing, that helps you know and understand not just yourself better but the world better.” When we think about poetry in particular we think about one of Dwayne’s most poignant barz describing the “secret sharers.” Because prison crams us into small spaces, proximity becomes its own force, pushing and pulling at the stiff distance binding flesh and architecture in a truth or dare standoff. Friend and foe alike either hide in plain sight or confide in the silence. Somebody has to loosen the grip on the frog so it can stretch its legs. Pens need to be pushed.

Incarceration necessarily strips away agency, so the arts become the weapons of necessity that exercise and amplify expressions of history, identity, trauma and hope when practical power is absent. “Books and art have been the only things I’ve encountered that always carry that magic,” Dwayne explains. “Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross’s book Your Brain on Art elegantly makes the case that art is essential to our lives and to our well-being.” We don’t even refer to books as books anymore around here – their titles are like monikers of cats on the tier, like people. We’re protective of them. Our Bastard’s title has these mysteriously knowing handwritten notes in it that make us think we came up on some sage’s book of coded spells – like notes in the margins of books that got excised from the Bible.

The arts amount to a language and a series of lenses that filter experience and emotion. “The other thing the arts do is make you feel less like the thing you don’t want to name,” Dwayne recently remarked, saying “they give you a way to remember… it allows me to see the world as more than what I was seeing before I got into trouble.” This sentence, right here, is the professorial magic of this dude’s whole get down. If only more of us had had a father talk to us about art and memory and perspective like that. Creativity begs for life in a place built for the choke of Gwendolyn’s calling. Art is why and how we persist – it’s our why and how, braided together. Van Jordan said poets write the history books, right?

Creating safe spaces that encourage the arts and democratize agency have a way of crossing folks over the self-imposed fault lines that the politics of prison can often entrench folks in. “Art will turn an enemy into a friend far quicker than any slogan,” Dwayne remarked, “and it’ll reveal something as unexpected to you as a full moon to a two year old. You know them fat blood moons that seem so close that you can touch it? A kid sees that the first time and it feels like a kind of magic.” The intersections of form hold the alchemy — music, verse and paint can save a life. Film them — you can save a people.

Dwayne, along with Randall, Mitch Jackson and Natalie Diaz each looked into a camera and supported the public association of our workshop with his organization, saying “Barz Behind Bars… Freedom Reads, I got you.” They each then posted their video shout-outs on their respective social media, giving our community a rare whiff of literary credibility. Dwayne and Randall then leaned into the nonprofit organization Benjamin Frandsen founded to coordinate our workshop’s development as advisors to its Board of Directors. He even gave us a greenlight to develop a performing arts audio podcast using his organization’s namesake to showcase the power of books. We couldn’t have asked for more. Dwayne has never really told us no.

We ascribe to a conceptualization of abolition that acknowledges the practicality of our circumstance and embraces Doran Larson’s call for carceral state residents to practice civic engagement as action work that so normalizes resident participation in civil society that it serves to eradicate the difference between citizen and convict. Our publishing ambitions and public-facing carceral journalism efforts that aim to illuminate the consequences of mass incarceration and center the lived experience of stakeholders is that action work that pushes against marginalization and resists that civil death prisons were designed for.

“Being against mass incarceration, whatever that means for folks,” Dwayne agrees, “is just one of the necessary things to be in this world today; being for finding ways to support those inside is the other essential thing to be.”

In our Barz workshop we review and apply Mitch’s approach to Re-Vision, as he sets forth in PEN America’s The Sentences That Create Us writing guide, to a poetry primer exercise that directs participants to re-create a select writer’s non-poetic work as a would-be poem, constructed entirely from the ingredients of copy living within the four corners of the author’s essay, lecture, paper, speech or book. This exercise is the first step towards crafting a poem without having to dream one up from scratch. It also drags the non-reader into the empathy pool and asks him to hunt for the author’s meaning while still giving him some creative agency over how he interprets the author’s work. It’s a primer.

For many, this is the first non-rhyming poem they have ever attempted. If it goes well, we will have broken the non-rhyming ice with them and demonstrated how cadence and vocal rhythm can compete with verses that rhyme. In fact, the first poetry exercise of this sort introduces Dwayne’s “Getting Out” essay, with the following prompt: Re-Imagine, Re-Vise and Re-Mix the following essay as a poem at least 24 lines long that doesn’t rhyme, conveys a theme put forth by the essay and uses only the words presented in the essay.

We then perform a reading of the following exemplar we created in honor of Dwayne’s work in order to set the bar and demonstrate how emotive and compelling poetry that doesn’t rhyme can be performed:

Post-Modern Virginia – Variation on a Theme by Reginald Dwayne Betts (Getting Out, 2019)

in Virginia — no stretch of time spent outside prison

would fill the distance between the world and me.

the greatest obstacle — brutally permanent, how I saw it. my crime: the caricature of a black boy in America.

vile, wicked, felon, beat-up and ink-colored.

presumed to lack the character — talking too much.

weed, the pistol, ignorance, my desire for a come-up collapsed into twenty-eight minutes, convicted — in Virginia. heartbreak, squalor, I was gravid with fear.

my becoming — clinging to the mandatory minimum

at age fourteen. prison was just too hypothetical for Bastards of the Reagan Era often near trouble — in Virginia. scraps of our identities, guns at our heads.

Clinton said, “super predators…bring them to heel.”

called five prisons home, wrote a thousand bad poems to find

the scarred me standing in the disappeared years — in Virginia.

something “less than worthy human beings.” ex-con.

the telling pained me — wondered if I’d lost my mind.

the greatest obstacle: All of Us or None? (didn’t know)

who I was learned how to wait while speed-reading on the floor — in Virginia. where Freedom was a Question demanded. An elegy for

secret sharers fraid to admit our cursive history.

law — my handwritten faded yellow confession.

brown-skinned me and krushed Keese, standing for count — in Virginia.

For the books, the access and the brutal honesty of your work — we salute you Dwayne. For the selfless collaboration and public support of our community and projects — we work tirelessly in hopes of proving ourselves worthy. For leveraging your literary and activist colleagues into our lives in service of a greater possibility of promise — we model that teamwork ethic by sharing this platform with our younger peers. On behalf of everybody who will walk past those bookcases, thank you for these unparalleled gifts and the promise that spills into us just by being proximal to your flex. We can’t wait to get lost in the cinematic documentary we know is coming.

You’ve given all of those who have — and still do — stand for count a solid and compassionate male archetype worthy of being respected and imprinted upon. Yours is the definitive youth offender reclamation story. It is our privilege to be able to harness some of your life’s work in service of the folks who might be transformed through the power of a book, confessional free writing and the unique felony fellowship found in the carceral performing arts. Owing to your creative humanity Dwayne, we don’t have to imagine freedom — you’ve placed it in our hands.

Support carceral literacy at www.freedomreads.org

Sophie Yoakum (Davis Vanguard), Nolan “Goon” Buchanan (Barz Behind Bars), Torrey “Skrybe” Thomas (Barz Behind Bars) and Elisa Plata (Ben Free Project) contributed to the production of this content. An excerpt of this content originally appeared in Columbia University’s School of the Arts’ literary magazine Exchange, 2023/Issue 4, Incarcerated Writers Initiative.

© 2024 Ghostwrite Mike & The Mundo Press. Published by Inner Views on behalf of Ben Free Project. All Rights Reserved. For permissions, please email:

ghostwrite@benfreeproject.org

© 2024 Inner Views. Copyright of Inner Views is the property of Ben Free Project and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiples sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder’s express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.