In just over a week, Californians will be asked to vote on Prop. 6, which ends forced labor in our prisons. The Vanguard recently sat down with Amika Mota of the Sister Warriors project who talks about her experience and perspective on the issued of forced labor and ending slavery in our prisons.

Vanguard: I am interested in your perspective of why you’re working on this issue and then maybe sharing how your experience relates to the issue of Prop. 6.

Amika Mota:

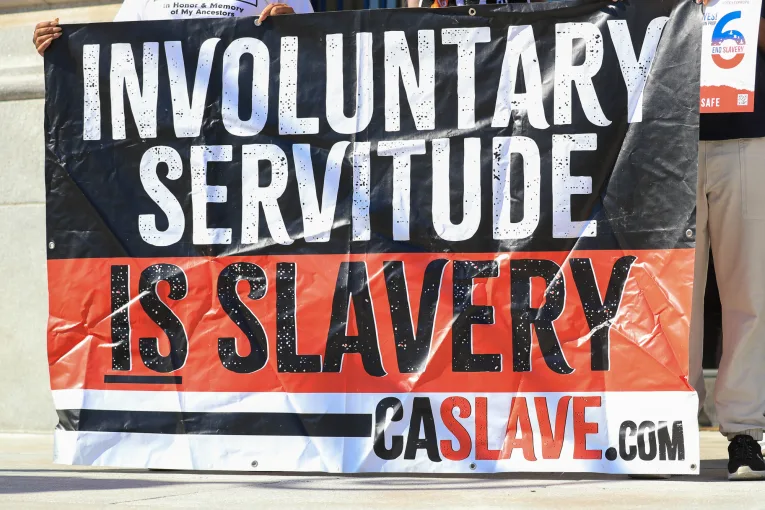

Of course. Yeah. Well, I’m so glad to be talking about it and to be talking about it to everybody that’s going to have the option to go vote on this November. It’s been a long time coming. I could say at Sister Warriors and just in the larger movement community, we’ve been working on this, what feels like forever in different ways. So we definitely have some history in this space working on this. When it was ACA three in 2020, a lot of lessons from what happened there and why the bill died that we were really able to kind of apply to this campaign with ACA eight and get it to the ballot, which feels really huge. But we’ve had a lot of history in this space talking about involuntary servitude and wages and also trying to kind of separate those issues because it became really clear that they just were so tied together, but we really wanted to address them separately.

And I would say that almost everybody that has done time, particularly in a state prison or a federal prison, just really understands the experience viscerally. We understand what it means to be forced to do something that we would choose not to do, and we understand the repercussions of those choices. And I would say that I think that as a gender justice organization, Sister Warriors, we definitely hold the lens and the perspective of how involuntary servitude has really affected women and trans folks in particular. And just to say a lot of people enter the prison system, particularly women and trans folks, having experienced domestic violence, forced labor is actually a very normal part of routine on the outside as well. A lot of women are forced into performing labor that they wouldn’t choose to do on their own. And it’s almost this continuation when we make it inside prison.

And so it just has always felt like a, really, it is always just felt really wrong. It’s like a lot of us are going inside, we’re doing time for a crime that we’ve committed, but it’s also our job to rehabilitate and heal. And when we see these kind of systems that are replicated inside of prisons that put us in these positions where of just having very little choice, it is painful to watch that. So I can say as someone that was a mama to three young children, when I first got into prison, I didn’t really understand the way that things worked on the inside. I knew that I was going to be excited to have a job that was, at that time it was, there was a three-year wait list to even get a job. So a lot of people had to fill their days with what you were going to choose to do to rehabilitate.

But I was put into a job assignment in my first year in prison. That would’ve been considered a fairly good job. It was an office position, it was office services. And so I worked closely with a teacher in a classroom setting. So it was definitely a better job than raking rocks or scrubbing dishes for 7 cents an hour. But what happened in that job is it became pretty clear within a couple weeks of me being there that it was not a safe environment for me. There’s a lot of background to it, but basically I knew I probably should not stay in that position. And I tried to get out, I tried to talk to administration about locating me somewhere else, and those requests were denied repeatedly. And so I chose to stop attending that work assignment rather than potentially losing my date or getting in trouble.

Some of the things that I knew that could happen if I stayed in that job… and the end result of that for me was getting three write-ups within a month and being then sent to at CIW at the time, CC, which is a classification you’re deemed as a failure to program was housed in the shoe. And so I was put in isolation for 45 days for refusing a job assignment. And I didn’t understand that. The repercussion of that was I didn’t talk to my children for 45 days. I had my first visit scheduled with my kids. I hadn’t seen them for a year and a half, and they were going to come visit me because I had made it to prison. But because of this writeup and then being moved to this housing, they had to cancel their visit. They wouldn’t be able to see me. And so it was just a real, for me, it was a rude awakening in my first year of prison of what it really means to be punished when you’re inside prison. And I felt like I was making a really rational common sense decision that would keep me safe as a woman. And the outcome of that was 45 days in the hole. And that’s just my little story. There are so many other people,

Vanguard: I think people that aren’t familiar with this issue are asking themselves this question, which is, you’re being punished for committing a crime. Why are you complaining about being forced to work? Don’t those two things go hand in hand?

Amika Mota:

Yeah. So I would typically never complain about working. I can tell you there was not a day that I spent in prison that I was not working in one way or another. And I had the range of jobs. I did have that dishwasher job in the kitchen. I did vocational programs. I always stayed busy. Most people don’t have a problem with working. Most people want to be engaged in both their own rehabilitation and healing and keeping the space that we live in. We want our space to be clean, we want our environment to look good, and people are willing to participate in that.

The difference between being forced into a job and choosing a voluntary work assignment, they’re just really different. And I do understand that the public perception a lot is when people are being punished, that they are not worthy of being treated like a human being on the outside. But the way it plays out for us when we do have a job in the inside, and again, most people want to work, most people, that 8 cents an hour is a huge difference for us. It’s what buys our hygiene every month. It’s what we could buy noodles and coffee with. But you don’t have the option to call in sick if you’re not.

Amika Mota:

In prison, you don’t have the option to say, hey, I need to work on my case because actually what I really need to prioritize is my freedom. And there are a lot of people that really do need to be doing work in the law library to try to work on their case. And those law library hours are open during the same time our job assignments are. Right. So sometimes people are forced to make really difficult decisions also.

Vanguard:

And that seems to be like the issue that a lot of people that I’ve talked to have brought up, is that it’s one thing, and I hear you, you want to work and you probably want to work for a lot of reasons. Not to mention you don’t want to just sit around and do nothing, but there can be a trade off between schooling and rehabilitation and work, and that doesn’t seem to be a great trade off.

Amika Mota:

Yeah, it’s not. I mean, we know that CDCR talks about rehabilitation. That is one of the components of what is supposed to be happening with incarcerated people when they’re doing time, is actually preparing to reenter and rehabilitate. And often we have to choose one or the other. And I don’t think that there would be any shortage of people willing to work. I mean, it really is, like I said, one of those, when I was there, it was a three-year wait list to even get a job. So people are lined up wanting to work, but the ability for the state to force us, we cannot separate that moral issue of involuntary servitude and those ties to modern day slavery. I just, it’s so hard for me to imagine how California can keep moving and grooving with involuntary servitude.

Vanguard:

Well, and that’s another issue that just boggles the mind, is that California continues to have the involuntary servitude exception to the 13th Amendment this day and age. And that just whatever you think about work in prison, that is really a weird thing.

Amika Mota:

Is so strange. And the idea that Utah has done this, Nebraska, Tennessee, California, I mean, if we don’t get this done in November, I just, it’s wild to me that California has not led in this area because it really, just like the …

Vanguard:

Do you see any other gender components to this?

Amika Mota:

Yeah, I do. I mean, I think that there’s, what I was kind of alluding to in the beginning was talking around the way that women in particular enter prison. And I guess what I should say is that I was saying it was continuation of a lot of trauma and harm. And this power dynamic I think is very relevant with women and trans folks because a lot of people come in there having been told and dictated how they live work, particularly in the underground street economy, it’s very normal for women to be managed and then entering prison. And that power dynamic, it is just a whole repeat of what a lot of people have experienced on the streets. And so for women in particular that are working on healing and gaining autonomy and figuring out how to live lives on the outside, that’s a way that the whole nature of things really affects women really differently.

A lot of people don’t fight back against job assignments. We just take ’em and do what we’re supposed to do. And the few that do are further tagged as troublemakers further criminalized by being housed in these isolated areas. I think that those are ways that we’re affected a little bit differently. And then also the relationships that we’re tasked with holding. Even when we go into prison, we are still in charge of our children in a lot of ways. We are in charge of keeping our family units on the outside functioning and together. And it requires a lot. It’s not like we can always just pick up the phone or now there’s tablets. When I was there, it wasn’t when we wanted to write to our children, we had to sit down with a paper and a pencil and we had to spend an hour writing to our kids.

All of those family connections that we’re really responsible for, in a lot of ways requires our time and commitment and energy. And so it’s something that we compete with our time to stay connected to our families and our loved ones when we’re being forced into labor. For sure. And then I would also just say that the economics of prison labor, of course we know that it’s about a hundred million, I believe, that California is saving on utilizing prison labor, and many of us have to go back and figure out how to take care of our families. So I think the whole system is a little tipped and it does definitely impact women a little bit differently.