When film producer Scott Budnick traveled to High Desert State Prison with actor and poet Richard Cabral over a decade ago, he summoned a select group of youth offenders into a room to tell them about his nonprofit organization’s effort to amend the sentencing laws in California in order to deliver redemptive hope to those placed upon the societal shelf for decades and denied the right of return. Louis Baca, a Bay Area youth offender sentenced to Life Without Parole (LWOP) for a drive-by shooting he committed as a teen, was present to hear about the Anti-Recidivism Coalition’s (ARC) plan to reset the rules in order to give juveniles sentenced to LWOP a path to freedom.

“I wasn’t supposed to be in that room,” Baca said, “as I wasn’t invited, probably because I wasn’t going to benefit from ARC’s legislative initiatives.” Budnick told the room that juveniles sentenced to LWOP were the first cohort of youth offenders his legislative efforts would target for advocacy, while encouraging them to recruit their families to enlist in ARC’s lobbying efforts. Baca asked him, referring to the youth offenders sentenced to LWOP aged 18 to 25, “what about us?” Budnick told him, “We won’t forget about you guys,” but said juveniles were the priority.

In the subsequent years, Baca has watched multiple laws get passed that give redemption to juveniles sentenced to LWOP and those youth offenders between the ages of 18 and 25 who are sentenced to indeterminate life terms—but nothing has been done for Baca’s offender category. “We are the forgotten youth,” Baca explains, citing the dissonance that resides in the legislative failure to reconcile why the developmental brain science that was cited by the United States Supreme Court to strike down automatic LWOP sentences for juveniles as unconstitutional hasn’t led to enough change. “We’ve been left behind.”

Several nonprofit organizations have cropped up in the name of LWOP advocacy, seemingly intending to lobby lawmakers for the legislative fix the courts have delineated as the providence of the legislative branch, only to fundraise and fail to pass any legislation at all. Drop LWOP and FUEL are two such groups that have failed to pass any LWOP legislation at all, while taking up most of the oxygen.

Because prevailing brain science affirms that the frontal lobe cortex doesn’t fully form until the age of 25, and the underdeveloped executive function capacity undergirds the claim of mitigation for youth offenders—and the concomitant opportunity to change—Baca argues that the inclusion of defendants formerly sentenced to death row who were given a reprieve from execution only by virtue of the moratorium imposed by California’s Governor and resentenced to LWOP by default, has complicated the prospect of a legislative fix. “If you expand the bill’s constituent cohort class to include folks who aren’t youth offenders,” Baca explains, “you necessarily lose the brain science argument. Why would anybody seeking a bill that can pass based upon the brain science mitigation willingly introduce into the cohort class a group of folks who are aged out of the argument?”

Indeed, infecting an LWOP bill with language that benefits folks aged beyond the youth offender parameter—beyond the age of 25—undermines the basis for the redemption argument, seeks parole for those who are not entitled to the brain science-based mitigation claim, and renders the bill predictably flaccid.

Following Supreme Court holdings that deemed LWOP sentences for juveniles unconstitutional, states like California began to examine how they determined who was salvageable and how best to afford long-term youth offenders a meaningful opportunity to demonstrate parole readiness. “Senate Bill 9 was passed in 2012 right after the Miller case,” Baca recalls, “which gave juvenile LWOPs a chance to petition their sentencing court after serving 25 years for a possible resentencing that availed parole eligibility based upon an assessment of remorse, rehabilitation, and circumstances of the offense.” A year later, the Golden State passed Senate Bill 260, which eliminated the petition hurdle for juvenile LWOPs and automatically made them parole eligible after 25 years with built-in diminished capacity mitigation determinations, based upon the hallmark features of youth, and a showing of subsequent growth and increased maturity.

Because California statute 4801(c) requires that parole suitability determinations “give great weight to the diminished culpability of youth as compared to adults, and hallmark features of youth,” most youth offenders who can get to a parole review will have a solid chance at release. However, the California youth offender parole statute (Cal. Pen. Code §§ 3051, 4801), which was first enacted in 2013 to impact only those who committed offenses while under the age of 18, has since been amended to include young adult offenders sentenced to indeterminate life terms—but not LWOP—whose crimes were committed between the ages of 18 and 25, affording to young adults access to staggered parole hearings during the 15th, 20th, or 25th year of their incarceration.

Youth offenders aged 18-25 at the time of the offense who are serving an LWOP sentence are excluded, though the brain science applies to them similarly by virtue of their age, based upon their static sentences and not any individualized case factors. They are deemed incapable of growth and change.

According to the Supreme Court’s decision in Graham v. Florida, the death penalty and mandatory life without parole are sentences that offer “no chance for reconciliation with society, no hope,” which amounts to a flat out rejection of rehabilitation, though for LWOPs aged 18-25 at the time of their offense, research shows the propensity for committing crime significantly decreases after age 25. If LWOP for those under 18 violates the Eighth Amendment because it ignores the possibility of growth and development, it necessarily violates the same rights of youth offender LWOPs aged 18-25, who, like juveniles, have the same claim upon the brain science. It’s high time California level the playing field for all persons under 25—impacted by the brain science—and do away with its arbitrary nomenclature concerning adulthood.

Age 18 has been revealed to be nothing more than a time-honored social convention dressed as a legal construct lacking any substantive neurologically significant distinction from any age along the 18-25 continuum.

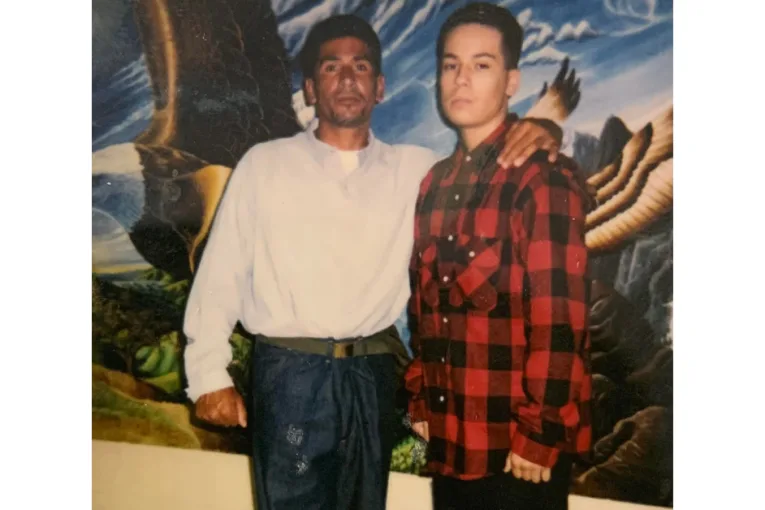

Baca has never said he deserves to be released, or argued he has served too much time. “I view my culpability through the lens of a child who lost his murdered mother at the hands of his father, and so, I identify with the plight of victims because I lost my mom to violence and my dad to prison.” He grew up parentless, looking to a gang for acceptance.

“I was a coward. I fired a gun from a moving vehicle at multiple people who were fleeing, running away, and unarmed. I deserve to have served three decades. But I also think that if my brain wasn’t fully formed at age 19, I should be afforded the chance to demonstrate my change in the same way as all the other 19-year-olds who killed somebody and are serving life sentences are now permitted to after 25 years. If lifers aged 18-25 get review at year 15, 20, and 25, is it so unreasonable to allow a similarly-aged LWOP a review at the high end of that stagger, after 25 years?”

In 2022, Baca spoke via phone with FUEL’s Geri Silva, seeking to urge her to push legislation that would help youth offender LWOPs. “She took my call, but said they wanted to abolish all LWOP sentences.” Each time such a bill has been attempted in California, the bill has been pulled before the vote due to low support. “I don’t think these attempts have had to be pulled because there isn’t support for the LWOP cause,” says Ben Free Project’s Executive Director, Benjamin Frandsen, a former life prisoner now studying in SDSU’s MFA program whose nonprofit organization delivers California Arts Council-funded programming to prisoner populations at California State Prison – Lancaster.

“I believe it’s because the ask has been too broad, and so, the youth offender LWOPs have been left to the mercy of the overreach,” Frandsen opined. “Any such bill needs to follow the incremental approach taken by Scott Budnick and ARC in order to make the legislative vote calculus safe for lawmakers. I reject LWOP, but I reflexively know too that the youth offender cohort within the LWOP universe is the only subset with a brain science claim, and thus, that group has a more equitable claim to the right of return than do those aged beyond 25 at the time of their crime and now deemed LWOP only by virtue of the Governor’s death penalty moratorium.”

Frustrated by the lack of legislation that might address the plight of his those in his circumstance, Baca wrote his own would-be bill, seeking to carve out a remedy for youth offender LWOPs that afforded a review process after the 25th year of confinement, based upon the same review criteria for all youth offenders. “I wrote it by hand in my cell here at Valley State Prison (VSP), the same place my dad paroled from after serving over three and a half decades, and mailed it to Henry Ortiz at All Of Us Or None. He gave it to AOUON‘s policy manager Geronimo Aquilar, who cleaned it up and had it certified by the Legislative Counsel’s office.”

His version never made it into any committees or to the floor, as it couldn’t compete with other bills—those bills pulled due to low support—already being lobbied for by the LWOP advocacy groups. “But I spoke on the phone with several staff members for many lawmakers who didn’t seem to know what a youth offender was and had no clue there was a better way to carve out our cohort from this larger ask being made of them by way of these bills seeking to end all LWOP. It showed me what the real problem was and who was responsible, but I had to suck it up, focus on my transformation process, and put it in God’s hands.”

In the interim, Baca has been selected to appear in a Compassion Prison Project video campaign for Fritzi Horstman’s Trauma Talks, was invited by two-time American Book Award-winning poet Randall Horton to appear on the Poetry Centered audio podcast by the Poetry Center at the University of Arizona, became featured by producers of The Kardashians reality show for his on-camera exposition about trauma reconciliation while seated with Khloe Kardashian, and appeared on the Everyday Injustice podcast via phone to talk about his life. “I can’t dwell on what I’m not given or allowed to do, or obsess about what might not be fair, not while there is a body in the ground by my hand. My duty is to be of service to my community, joyfully, wherever that happens to be, for as long as I’m alive to do so—if that means this prison—then so be it,” Baca says.

“I wish there was a way for my victim’s family to engage me and let me convey to them what circumstance has kept shadowed. Justice means ownership, reparations, and healing. I didn’t have parents, and there are parents who don’t have their son—a family and community who lost the human flower I ripped from the garden. I carry deep guilt, real shame, and a serious remorse that I know nobody will ever credit me for having at all, but one day I hope to sit in a room with the family I harmed and apologize.”

He says it’s difficult to negotiate wanting to live while the system waits for you to die. “It’s hard to smile, laugh, or even do these media hits, because I know that without context, it all probably looks self-serving and makes my victim’s family recoil. I dwell on that daily. At the same time, I am that terrible example of having “no hope” of being free, and so, if I’m ever going to pay my debt to the universe, I must be sincere in my mentorship of others, and righteous in my grown man modeling of what change might look like for those younger men here who will enjoy the right of return, because the only real contribution to the improvement of public safety I might ever make at all is being the exemplar these younger versions of me can imprint upon. They are going home, and if they take a piece of my change with them, the world will be safer by a sliver.”

The annual legislative session is upon us. December marks the window of time when the lobbyists flood the zone and bills get pushed through committees. There is a wave of conservatism rushing through the electorate—the woke DAs have been sent packing, and Prop. 6 was rejected by the voters. Will there be an LWOP bill this year that takes a measured bite at the real problem and evens the scales for all youth offenders ages 18-25? We’ve heard rumblings that Budnick is making a move.

“I’ve heard the same rumors,” Baca admits, “but nobody really knows what that dude does—he’s like Yoda. He uses the force. All I can do is go to class, mentor my guys, facilitate my Barz Behind Bars poetry cyphers, and get ready for Common’s Rebirth of Sound program to launch in December. Music saved my life a thousand times. Poetry gave me medicine for my pain. Spoken word taught me how to master my symptoms. Insight gave me healing for my traumas. Being honest about my flaws and insecurities brought real friendship into my life. Whatever happens with the laws, I’ll be here for it, and I’ll be serving others.”

When he walked at his community college graduation and shook the Warden’s hand, Baca felt like he’d accomplished something—something the free world calls meaningful. “Nobody I knew in my old life ever even finished high school, let alone lived that long. Nobody I knew on the streets got an AA degree.” Recently notified by VSP’s Postsecondary Education Coordinator Gregory Gadams that he’d been accepted for admission into CSU Fresno’s BA degree program, Baca nearly cried reflecting on the moment. “I feel oddly worthy of this. I’m humble as heck to have this opportunity, but I’m also kind of beginning to let myself believe that I was always capable of more than what the world allowed me to believe. There is a different version of me forming. I can feel myself shape shifting. I’m becoming.”

Louis “Last Jedi Left” Baca, is a Barz Behind Bars workshop facilitator, member of the Vanguard Carceral Journalism Guild writing corps, a producer of the Inner Views lecture series, and a member of the performance poetry collective Broken Soulz. Listen to his Everyday Injustice podcast appearance here.