Less than a decade ago, Brant Choate, then the Superintendent of the Office of Correctional Education charged with overseeing the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) educational programming, told Corrections Forum that “fifty-two percent do not read at a ninth grade level—reading is the bread and butter of our business.” Less than a decade before then, CDCR’s recidivism rate was sixty-six percent to twenty-six percent higher than the national average. Recidivism snitches on illiteracy.

Despite shrinking the department’s carceral state resident population from 144,000 (circa 2011), to just over ninety thousand now, when Choate appeared on the CDCR Unlocked podcast in late 2022 in a new role as the Director of the Division of Rehabilitative Programs (DRP), he cited how thirty-eight percent are still illiterate, owing to not having acquired a high school diploma or GED. Acknowledging the literacy-recidivism-public safety nexus, Choate said “these people” are at the greatest risk to recidivate “if we send them home that way.”

What is the takeaway here? Did any of you take statistics in college, dabble in linear regression, or hypothesize probabilities?

Well, shedding close to 55,000 captives (clients) represents a nearly forty-eight percent drop in the number of “students” CDCR has had to teach since operating at a level of overcrowded capacity the Supreme Court deemed in 2011 to be violative of the Eighth Amendment. With about half as many folks to teach, and an ever-ballooning budget to play with throughout the fifteen year culling period since, CDCR hasn’t gotten better at teaching English proficiency. If you were to consider CDCR as being one giant school, you’d have to ask yourself: “How badly managed must that school be if after losing half its student body, it still has a near forty percent failure rate?”

To his credit, Choate invited our mentor Reginald Dwayne Betts’ then-Million Books Project into CDCR via multiple press releases touting literacy. By the time the first nine thousand books landed in California at Valley State Prison (VSP) in early 2023, Betts’ program had been renamed Freedom Reads, and soon thereafter we were the first in-prison community using that curation as the pedagogical reading prompt spine within our grass-roots Barz Behind Bars (B3) Critical Reading Creative Writing Performance Art workshop. Our fifteen-week cycle has graduated over two thousands participants—mostly BIPOC youth offenders, is operational at eleven CDCR facilities, and is deployed in seven different states inside youth detention facilities.

Slightly more than sixty-eight percent of the participants who have completed our B3 workshop cycle at VSP graduate high school or achieve a GED, and within one year over eighty percent of those B3 participants enroll in college for the first time in their lives.

Higher education linked to the return of Pell grant eligibility for incarcerated students represents a panacea for prison administrators, since not only do federal grants provide services state budgets need not cover, graduation positively impacts the rate of recidivism—higher education leads to quantifiable desistance. The more education confined people receive, the less likely they are to recidivate.

California has normalized its use of state budget resources to fund community college programming inside prisons, thanks to the groundbreaking work done by Rebecca Silbert (UC Berkeley’s School of Law) and Debbie Mukamal (Stanford Criminal Justice Center at Stanford Law School), two lawyers who nearly a decade ago performed a Ford Foundation-funded strategic analysis of how the state’s higher education ecosystem was serving justice-impacted residents of the carceral state. Their subsequent consortium work via Renewing Communities effectively built the current college programming structure BIPOC students have access to.

The California Model of carceral state management currently touted by CDCR, has among its four operational pillars a mission of fostering a culture of normalcy, which aims to create as-close-to-real-world experiences for residents in all spheres of life, with a particularly-focused effort to make the college experience as unlike the rest of prison as possible. Ironically, that mission has been achieved at VSP, inasmuch as there are hardly any Black students in any of the college classrooms. “I was one of two Black students in the BA program,” said JJ, a Peer Literacy Mentor.

Unfortunately, no matter how available and funded the community college verticals may be for residents, if they can’t migrate out of the ABE highschool experience, the prospect of higher education remains out of reach. Because a majority of the youngest offenders in the system are BIPOC residents under the age of twenty-six, and thus are already disproportionally overrepresented overall, they are also disproportionally overrepresented within the discrete cohort of ABE students who are idling without graduating. Conversely, BIPOC youth offenders are woefully underrepresented among the community of enrolled college students, to a degree that is palpably noticeable in every college classroom.

Not enough is being done to reimagine how best to engage young urbanized residents stuck in highschool who don’t already read, don’t write well, and are not proficient public speakers.

Real world professors travel in to teach in-person classes for students who use WiFi-enabled laptops with a modified Canvas shell that allows for remote upload/download of assignments and intra-class student chatrooms and message boards outside of class. At VSP, though confined college students are pursuing AA, BA, and MA degrees and taking night classes via multiple program providers, there is scant new student skill development in the areas of critical reading, research, writing, and public speaking for BIPOC youth offenders to lean into.

When we started hunting for structural spaces that presented opportunity zones, wherein we might be able to curate novel and nontraditional out-of-classroom engagements that harness technology tools in order to familiarize BIPOC youth offenders with modalities that develop their skillset deficits, we conceived of how best to augment existing resources to train new college students for debate society participation. Yes—after banging the drum about the absence of basic skills modalities, we see the solution as preparing the most skills-challenged college students in prison for the debate stage.

We believe our Inside Knowledge project represents a hydra of easy-to-implement programming that could potentially on-board reading, writing, and public speaking skills development so well, that it could be worthy of a revolutionary carceral audio podcast format and university-backed digital humanities archive that reframes what in-prison debate society could become, resets how prison-to-prison debates could best be produced and normalized, and pioneers how imprisoned college students author the first-person testimony that contributes to and preserves the carceral state historical record – as it happens.

Creating audio-only debates that are recorded within any prison’s media center would allow a single workstation, augmented with wrap-around microphones, to be used as a virtual stage, whereby debate participants use their EBSCO database-enabled laptops to research their issues, craft their arguments into a Word document, and read them aloud for sound capture. Edited together, this simple production format would result in a seamless back and forth listening experience that presents the audience with a virtual debate, while allowing novice debaters to improve their skills and normalize participation.

Over time, these virtual debate sessions will exercise the five main muscles (critical reading, research, argument formation, writing, and public speaking) that new students will need throughout their college careers in order to succeed and not become discouraged as the rigor increases.

We also conceived of a more equitable way to diversify the debate process, by breaking apart the student cohorts ala weight classes, such that new students with less than 60 units, those with between 60 and 120 units, and those with BA degrees compete in leagues against similarly situated students, such that each debate event involves at least three actual challenges, involving each category of student. Having the best debaters and the most accomplished students constitute the only team that gets to debate, necessarily excludes everyone else and affirms the sorts of structural problems that account for why there are so few Black students in the program to begin with. Consider this an insurgent reset of the status quo – as another of our mentors Randall Horton flexes in his Radical Reversal album—this is a “reordering of the ordered order.”

Then we built an unhosted, yet narrated, docu-style testimonial template for a similarly titled audio podcast that centers the transformational narratives of student stakeholders matriculating through college life while in prison – a format that has yet to be captured and produced with clear-eyed intentionality. Collectively assembled, each of these elements could not only scaffold a new student’s aptitude development and performance success in multiple key skills areas, the resulting content would likely humanize stakeholders in a manner that could populate a digital humanities archive, thus preserving the historical record for carceral studies scholars to evaluate. If debates reflect civil societal discourse, let us train our stakeholders in the art of forensics.

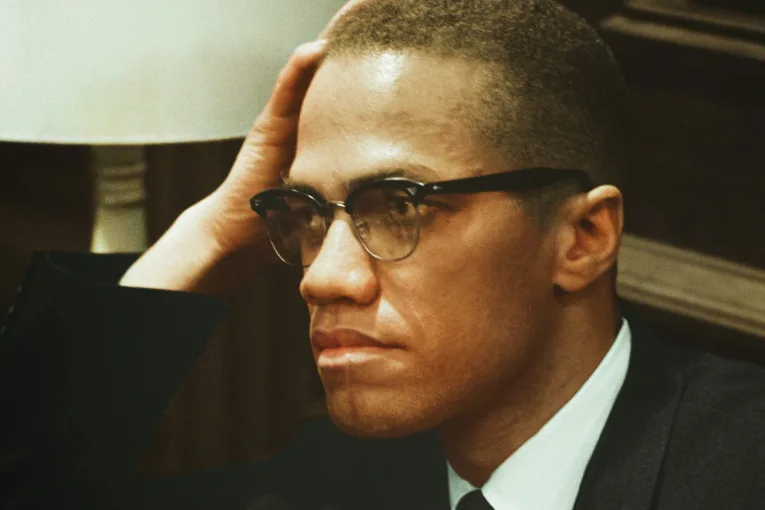

Another one of our mentors, author and scholar Elizabeth Hinton, while teaching at Harvard in 2018, was instrumental in staging an in-prison/in-person debate at MCI-Norfolk, a medium security prison near Boston, Massachusetts, between students from the Harvard College Debating Union and the Norfolk Prison Colony Debating Society. Designed by a Harvard alum in 1913, MCI-Norfolk, which formed its first debate team in 1933, defeated Oxford University in an international debate staged in 1951 with Malcolm X on its debate team. Though entering prison with an eighth grade education, Malcolm X would leave confinement and hold court (and the nation’s rapt attention), at Yale, Harvard, Columbia, MIT, UC Berkeley, Howard, Morgan State, and Clark College, among many others—demonstrating how reading, writing, persuasion, and speech could propel ideas forth and move humanity. Literacy changed Malcolm X’s life.

He also became banned (like how books can be), silenced (like how censorship can muzzle), and then assassinated (like the civil death prison is designed to deliver)—he became a Rubik’s Cube of metaphors reflecting a different yet similar horrid hue of carceral life.

Garret Felber, a noted historian and educator who worked with Hinton to stage the Norfolk-Harvard debate, chronicled Malcolm X’s insurgent debate and lecture prowess for the Journal of Social History, which has shaped our appreciation for how the books Freedom Reads has gifted to us, might be the brain food diet that best sustains our BIPOC students en route to ABE graduation. In another essay for the Journal of American History, Felber served up a portrayal of Malcolm X’s four days of testimony in the SaMarion trial, consisting of a clash with Columbia University professor Joseph Franz Schacht expounding on the difference between a “House Negro” and “Field Negro” before a federal judge, distinguishing between “segregation” and “separation,” and deftly deconstructing his use of “annihilate.”

Regardless of how Malcolm X’s rhetoric may have been framed against the pacifist aims of the NAACP, it was the books he found in prison that empowered him to transform himself into one of our nation’s most nimble and powerful orators. His was a didactic insurgency that defended separatism on the most visible of stages while being smeared as a threat to the established order. Similarity, as Gail K. Beil writes for the East Texas Historical Association, the great debaters groomed at Wiley College during the 1920s and 30s—when “intercollegiate debating among Negro institutions in the southwest” was initiated—who went undefeated against Fisk, Morehouse, Howard, Virginia Union, Lincoln, and Wilberforce, paved the way for what Elizabeth Ross, a project manager for Harvard University’s Institute of Policing, Incarceration, and Public Safety, recently described to us as a “FUBU ethic,” (for us, by us).

Imprisoned debaters don’t need an Ivy debate competitor in order to make their debate cultures viable—they just need to follow the example set by what Benjamin Bell described in American Legacy as “a little Jim Crow School from the badlands of Texas.” Shut out of the Pi Kappa Delta membership via racism, James Farmer, Jr., a Wiley debater mentored by his English professor Melvin Tolson, who would spar with and defeat Malcolm X four times, debated under the banner of a self-made Greek-named speech and debate fraternity, Alpha Phi Omega, which served historically Black colleges.

Believing college students living in confinement need to follow suit, we propose that the Inside Knowledge Carceral Forensics Society (IKCFS) be that big tent collective that sanctions and coordinates inter-prison debates, much like how our Vanguard Carceral Journalism Guild encompasses all journalists not toiling within the Prison Newspapers Industrial Complex. Next, we propose a university partner be sought to archive these intellectual gladiator matches in order to cultivate the historical record of the carceral state currently being ignored.

Resolved.