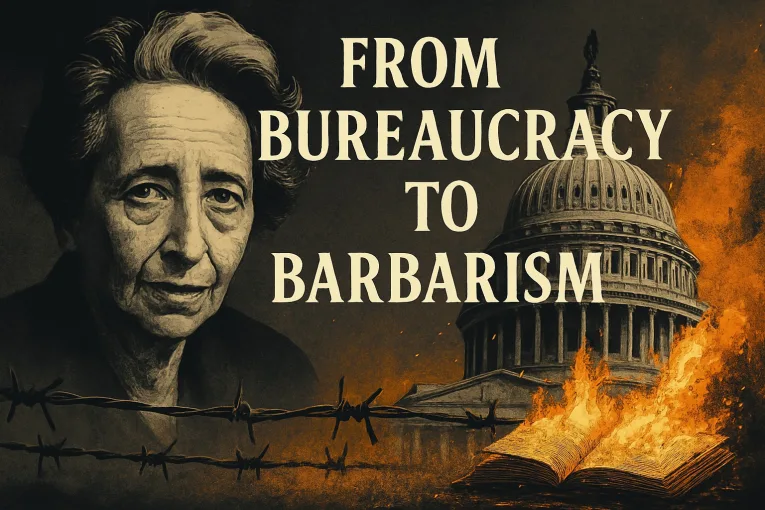

In 1963, political theorist Hannah Arendt observed something terrifying at the trial of Adolf Eichmann: that one of the architects of the Holocaust did not appear to be a monster. Eichmann was not a sadist, nor a fire-breathing ideologue. He was a man who obeyed orders, followed procedures, and rarely thought about the consequences of his actions.

Arendt described his demeanor as bland, even banal, and coined one of the most haunting phrases in modern political thought: the banality of evil.

“The sad truth,” she wrote, “is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.”

Arendt was not excusing Eichmann. She was identifying something much deeper: that atrocities are often not carried out by fanatics, but by ordinary people working inside systems—people who stop thinking, who stop questioning, who become cogs in a machine of cruelty.

That same mechanism of systematized injustice is turning again. And this time, it is spinning at Guantánamo Bay.

On March 20, 2025, The New York Times reported that the Trump administration had resumed transferring migrants to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba—this time under the pretext of national security.

An ICE charter flight from El Paso carried roughly 20 migrants, mostly Venezuelan men, to the military base, where they are now being held in a facility once used to imprison suspected members of Al Qaeda.

Officials have offered no public evidence for their repeated claim that the migrants are members of the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua. Many have no criminal records. Most have not been given individual hearings. Instead, they are being detained under a wartime relic: the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, which Trump now cites as legal grounds to bypass immigration law entirely.

The administration has deployed nearly 1,000 U.S. government personnel to Guantánamo—including 900 military service members and 70 DHS contractors—to operate a two-site detention complex: one in Camp 6, a maximum-security facility built for terrorism suspects, and the other in a repurposed migrant dormitory. It is a calculated decision, and a deeply symbolic one: to treat asylum seekers not as desperate families seeking refuge, but as enemies of the state.

And this is not a one-off act. On March 15, the Trump administration flew 238 Venezuelans to El Salvador, where they were placed in a high-security prison, again accused—without trial—of gang affiliation. Others were flown to Honduras and handed over to the Venezuelan government.

The U.S. is reengineering the Guantánamo model—indefinite detention, military oversight, legal opacity—for use in immigration enforcement.

Guantánamo Bay has its own dark history—it was never just a place. It was a legal black site, a warehouse for suspicion, a vacuum where the rule of law went to die.

Its resurrection for immigration control isn’t just a shift in policy. It’s a moral rupture. And many of us are watching it unfold in silence.

This is not the first time we’ve seen this logic at work.

In The Mauritanian (originally Guantánamo Diary), Mohamedou Ould Slahi recounts his experience of being tortured and detained for 14 years without charge in Guantánamo. His story is not one of rogue interrogators or isolated misconduct. It is the story of an entire system designed to deny due process while maintaining the appearance of order.

What haunted him most wasn’t just the pain—it was the cold professionalism of the people around him.

“You’re holding me because your country is strong enough to be unjust,” he told one of his interrogators as recounted in his memoir.

His captors made no secret of their power, but often hid behind procedure. One agent told him: “There is nothing incriminating, really. But there are too many little things. We will not ignore anything and just release you.” (Location 3356)

Once again we see: bureaucratic cruelty, detached from truth or justice.

Slahi’s experience reads like a case study in Arendt’s theory. His guards followed protocol. His interrogators cited national security. His jailers said, again and again, that they were “just doing their jobs.”

Slahi was waterboarded, sexually humiliated, and sleep-deprived for months—yet his captors considered themselves professionals, not abusers.

“Crime is something relative,” Slahi wrote. “It’s something the government defines and redefines whenever it pleases.”

In that system, innocence becomes irrelevant. Process becomes everything.

Now, that same structure is being pointed toward migrants.

Arendt warned us that totalitarianism does not need fanatics to flourish—it needs systems that strip people of moral responsibility. Slahi showed us what it’s like to live inside such a system. And the Trump administration is now building the infrastructure to scale it.

Let’s not pretend this is about law and order. This is about dehumanization. Migrants are being branded as enemies. Courts are being bypassed. Wartime laws are being weaponized against asylum seekers. The legal architecture of the War on Terror is being repurposed for immigration.

“When the military sets itself in motion,” Slahi quoted a German proverb, “the truth is too slow to keep up, so it stays behind.”

How long before that motion becomes momentum? How long before the exceptional becomes normalized?

If Guantánamo is allowed to become a standard tool of immigration policy, we are not only failing migrants—we are failing the idea that government power should be constrained by law.

In Eichmann in Jerusalem, Arendt remarked on how the machinery of Nazi governance enabled genocide without requiring personal hatred or moral conviction. That’s what made Eichmann so chilling. He wasn’t a villain in the traditional sense—he was an administrator.

“The longer one listened to him,” she wrote, “the more obvious it became that his inability to speak was closely connected with an inability to think.”

That is the final danger: not only that evil will be done, but that it will be done thoughtlessly—justified by systems, performed with indifference, and perpetuated by people who no longer see other people at all.

In 2025, America is not yet a police state. But Guantánamo already is. And if we do not resist this transformation now, the next stage may come quietly—through memoranda, flight manifests, and sealed court filings.

History is giving us another chance to think. We should take it.

Nazi comparisons are almost now a daily event on the Vanguard.

The main comparison point is actually the Guantánamo model which I applied the Banality of Evil frame from Arendt, so there really is no direct comparison to the Nazis.