By Julietta Bisharyan and Nick Gardner

Incarcerated Narratives

The sight of his sister through the barbed wire fence at Folsom State Prison was supposed to mark the end of a grueling 22-year sentence for Kao Saelee.

Instead, the former incarcerated firefighter was placed in chains and shackles by private security contractors working on behalf of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and flown to an ICE jail in Louisiana, nearly 2,000 miles from home.

Saelee, who worked as a part of California’s incarcerated firefighter team during the 2018 and 2019 wildfire seasons, will now face deportation to Laos — the country that his family fled as refugees when he was just 2 years old.

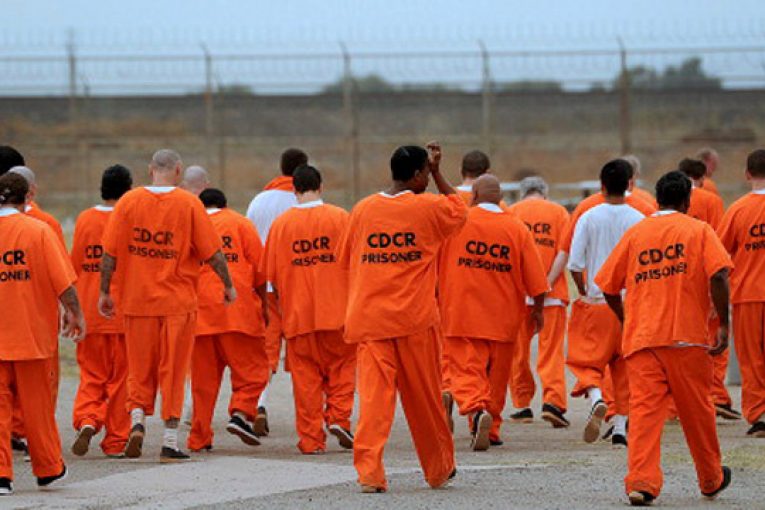

Despite his contributions to ensuring public safety, CDCR made the decision last month to cooperate with ICE and ensure that federal agents were able to incarcerate Saelee indefinitely upon his release.

“I paid my debt to society, and I think I should have a chance to be with my family,” Saelee said in a recent call from the Pine Prairie ICE Processing Center. “What is the point of sending somebody back to a country where they don’t have no family? I would be frightened out of my mind.

Saelee’s impoverished family settled in California’s Central Valley after fleeing a refugee camp in Thailand following the Vietnam War. Growing up, Saelee was responsible for taking care of his younger siblings, and was a role model to his nine younger cousins.

At school, Saelee was constantly bullied as he struggled to fit in with his majority-white classmates. Coupled with the stress of life at home, Saelee turned to drugs at a very young age, abusing substances “to medicate my mind and get away from all the craziness of life” as just a 10 year-old boy.

At age 18, Saelee’s father kicked him out of the house. What ensued was a struggle with addiction and homelessness that led him to participate, and be arrested, in an armed robbery in 1998. The young, legally inept Saelee signed a plea deal admitting guilt to charges of second-degree robbery, firearm assault and attempted second-degree murder in exchange for a 25-year prison sentence.

“I didn’t know nothing about the law,” Saelee admitted in an interview. “I just wanted to get it over with, so I took whatever they gave to me.”

While in prison, Saelee was visited by his family once every few months. However, upon being transferred to a new prison in Southern California, Saelee’s family was no longer able to travel to him.

As his sentence came to an end, Saelee discovered that he would be eligible for the incarcerated firefighter program— largely due to his good behavior.

Despite pay as low as two to five dollars per day, Saelee described being grateful for the one-dollar-an-hour he earned fighting wildfires, which was a clear upgrade from the 8 cents incarcerated individuals earn per hour working most prison jobs.

“It’s hard work, but for me it was worth it to see the look on people’s faces when they know they got people out there trying to help them save their land and their homes,” Saelee said of his work.

Unfortunately, as Saelee battled wildfires on the front lines, he became distanced from the support systems he had built through rehabilitation programs, self-help classes and church. As a result, he fell back into the cycle of substance abuse and addiction, which resulted in his removal from the firefighter program.

However, Saelee still has hopes of a firefighter career after prison, a once far-fetched prospect made possible by recent California legislation allowing for former incarcerated firefighters to have their records expunged and ultimately require EMT certification.

Despite positioning himself as an opponent to President Donald Trump’s pro-deportation agenda, Governor Gavin Newsom has defended this practice, which is not required by law.

The CDCR complies with ICE requests and informs the agency of release dates for certain individuals, and oftentimes facilitates transfers such as Saelee’s. Recently, Newsom responded to criticisms of the practice by saying “it’s been done historically” and that it was “appropriate.”

Data from the months of January through May have suggested that the CDCR has released more than 500 to ICE custody, even withstanding large outbreaks of coronavirus that have claimed over 65 lives throughout the CDCR system.

As for now, Saelee will wait in custody as removal proceedings are formalized.

“It would be like the first time I’m walking into the prison system – scared and just lost,” Saelee said of a possible removal from the United States. “If I do get deported, it’s like getting sentenced again, for life.”

CDCR Confirmed COVID-19 Cases and Outcomes

As of Oct. 2, there are a total of 14,643 confirmed COVID-19 cases in the CDCR system – 1,769 of them emerged in the last two weeks. 11.8% of the cases are active in custody while 3% have been released while active. Roughly 84.7% of confirmed cases have been resolved.

There have been 68 deaths within the CDCR facilities. Eight deaths have been reported just this week.

One of the deaths was at Folsom State Prison (FSP), marking the first incarcerated individual at the facility to die from what appears to be coronavirus-related complications. The person died at an outside hospital, according to CDCR.

Half of the population at FSP has caught the virus with 255 currently active and in custody. At least 63 employees at the prison have also tested positive as the outbreak, which skyrocketed in mid-August, surpasses 1,000 cases.

“The department is monitoring the situation very closely,” CDCR spokeswoman Dana Simas said in a statement. “There is an incident command post which is in coordination with the court appointed Federal Receiver at the prison. We have, since the beginning of the outbreak, implemented serial testing for inmates, increased staffing, and facilitated isolation for those that have tested positive to COVID-19.”

Seven other deaths this week have been reported from Avenal State Prison (ASP), San Quentin (SQ), CA Institution for Men (CIM) and Salinas Valley State Prison (SVSP).

Since Sept. 14, CDCR/CCHCS has partnered with Center for Restorative Justice Works, the organizers of the “Get on the Bus” program, to help exchange messages of hope between families and individuals who are incarcerated with a pilot program called, “Beyond the Bus.” According to CDCR, the project will be expanded to other institutions in the near future.

On Sept. 21, a memo was issued on new procedures for the transfer of COVID-19 resolved patients.

Asymptomatic resolved patients who have met the criteria for release from isolation and are within the 12-week protection window are considered safe to move or transfer without testing and quarantine. They are not required to be quarantined upon arrival in single cell housing or in cohorts, but need to wear an N-95 mask during transportation to avoid potential confusion during the transfer process.

Patients who have recovered from COVID-19 and are beyond 12 weeks from the onset of symptoms or from the first positive test for patients who were asymptomatic, are considered newly susceptible to reinfections. They are required to follow all directives in the Movement Matrix.

Lastly, patients with undiagnosed symptoms of influenza-like illness, influenza symptoms or COVID-19 symptoms are considered infected with COVID-19 until proven otherwise. These patients should not be moved or transferred except in the case of emergencies and must be immediately isolated to a single cell. They are also required to wear a surgical or procedure mask.

On Sept. 24, a new guidance for state employees on COVID-19 was issued, detailing the actions employees must take to avoid contracting COVID-19 and what to do after developing symptoms or testing positive.

The population of incarcerated persons has decreased by 24,265 since the beginning of the prison outbreaks in March. There are currently 98,144 individuals incarcerated in the CDCR facilities.

COVID-19 Developments In San Quentin

San Quentin State Prison went weeks without a major rise in COVID-19 cases. However, the two new deaths this week could be a sign that the prison’s early-pandemic troubles may be returning.

This week, San Quentin reported two new deaths, raising the death toll to 28. The other 26 deaths, excluding that of 55 year-old prison guard Gilbert Polanco, occurred during the months of June and July when the prison was experiencing a massive outbreak.

Earlier this month, CDCR’s first wrongful death lawsuit was brought forth by the children of 61-year-old Daniel Ruiz, an incarcerated person at San Quentin. Cited in the claim is the prison’s mishandling of transfers from other institutions, which is recognized as the impetus for San Quentin’s deadly outbreak in May.

On May 30, 121 incarcerated individuals were transferred from the California Institution for Men to San Quentin. None of these new transfers had been tested for coronavirus in the past month, and at the time of their arrival San Quentin had not yet reported any cases.

As of today, over 2,240 cases have been confirmed at San Quentin.

Ruiz had been serving time for a nonviolent drug crime and met the requirements for the CDCR’s early release program. At the time of his death, Ruiz had only a few months remaining on his sentence.

“The folks in our prisons are human beings,” said Michael Haddad, attorney for the Ruiz family. “Many who died at San Quentin had done non-violent crimes and should have been coming back home to their families soon. It is tragic and unacceptable that some prison bureaucrats treated them as less than human.”

A number of politicians have also come out against San Quentin’s decision to receive transfers in May. Assemblymember Marc Levine went so far as to label it “the worst prison health screw-up in state history”

The lawsuit also points to San Quentin’s communal living quarters with old-fashioned barred cells — outdated infrastructure that makes it impossible to effectively quarantine sick individuals.

Researchers visited the institution in early June and found “grave” conditions, their report of which was published in Nature, a weekly scientific journal.

“Given the unique architecture and age of San Quentin (built in the mid-1800s and early 1900s), there is exceedingly poor ventilation, extraordinarily close living quarters, and inadequate sanitation,” the researchers published in a memo following their visit.

Also Included in this memo was a solution to help mitigate the spread of the virus within San Quentin: “We therefore recommend that the prison population at San Quentin be reduced to 50% of current capacity (even further reduction would be more beneficial) via decarceration. … It is important to note that we spoke to a number of incarcerated people who were over the age of 60 and had a matter of weeks left on their sentences. It is inconceivable that they are still in this dangerous environment.”

So far, CDCR has expedited the release of over 3,500 incarcerated individuals across the state. At a hearing on July 1, held by California senators with the goal of establishing the root of problems at San Quentin, CDCR Secretary Ralph Diaz confirmed that incarcerated individuals with 180 days or fewer on their sentence, as well as nonviolent and at risk individuals, will have their sentences expedited.

CDCR Outbreaks’ Effect on the Public

Last month, the First District Court of Appeals heard oral arguments in In re Von Staich, a habeas case concerning the early release of individuals at San Quentin State Prison.

This legal analysis is based on UC Hastings Law Professor, Hadar Aviram’s work.

The hearing commenced with a debate determining whether CDCR should have provided evidence refuting claims made by physicians pertaining to conditions inside the prison. Initially, CDCR rejected the findings of the investigation, but did not release evidence to prove their stance.

In contention were with CDCR’s claims that incarcerated individuals at San Quentin were provided cleaning, sanitation and masks, and CDCR’s statements that downplayed the severity of the outbreak.

Kathleen Wilson, representing CDCR, argued that the habeas rules did not require the release of such evidence, and furthermore motioned the court for an evidentiary hearing. Brad O’Connell, on behalf of the petitioner, put forth arguments convincing Justice Anthony Kline, who deemed the prison’s response “conclusionary statements, not facts.”

Siding with the petitioner, Justice Kline recognized the likely presence of inaccuracies in CDCR’s accounts.

“What we believe this case is about”, said Justice Kline, “is whether there is persuasive evidence that the court must do what the Plata court cannot do, which is to reduce the population of San Quentin to a level that can permit the administration of social distancing within that prison.”

Ms. Walton then proceeded to suggest that CDCR efforts to contain the virus were being hindered by uncooperative individuals refusing to test or report symptoms. Justice Kline, however, countered with an observation prevalent in many incarcerated narratives, which is that most folks seek to avoid solitary confinement. Medical isolation in units notorious for cruel conditions and lasting mental health repercussions for incarcerated individuals is not an appealing prospect.

The topic of discussion then shifted to release policies, where Justice Kline identified the group most suited for early release — aging individuals who have been incarcerated for an extensive amount of time. In this case, the AG representative deemed the petitioner “a moderate risk.”

According to Aviram, the court proceedings favored the petitioner. However, Justice Kline stopped short of issuing an order for CDCR to release 50 percent of its prison population, stating such an order as “something I’m not sure I’m willing to do. . . not confident that my court has the ability.”

What the court did do, however, was express their intention to overly impede on prison business via a direct release order. According to Aviram, CDCR is in need of court guidance, which has been made clear by their poor response to the pandemic. Even their current plan is outdated and may take nearly a year to implement as individuals continue to get sick and die, prompting a proposal by the petitioner suggesting the priority of releases be determined foremost by age and medical condition.

Confronted with an alternate plan deviating from proposed CDCR strategy, the CDCR representative assured that there was “no need to act hastily.” The representative supported this attitude by citing CDCR early releases that occurred after the call to release 50 percent of incarcerated individuals (aka that the process was already underway), as well as a new program for sanitation and PPE equipment. However, Justice Klein was not having any of it.

“Yes there is. Yes there is. There is a need to act hastily.”

The court’s final decision is pending and highly anticipated.

CDCR Staff

There have been 3,726 staff cases in the CDCR facilities. 929 are currently active, and 2,797 have returned to work.

CDCR Comparisons – California and the US

According to the Marshall Project, California prisons rank fourth in the country for the highest number of confirmed cases, following Texas, Florida and Federal prisons. California makes up 10% of total cases among incarcerated people and 5.8% of the total deaths in prison.

There have been at least 3,644 cases of coronavirus reported among prison staff. 9 staff members have died while 2,783 have recovered.

Division of Juvenile Justice

As of Oct. 1, there are no active cases of COVID-19 among youth at DJJ facilities. 68 cases have been resolved.