By David M. Greenwald

Berkeley, CA – While racial disparities in everything from health, policing, and the criminal justice system have gained widespread attention over the last year, researchers for the “Roots of Structural Racism Project” at UC Berkeley found “there remains a surprising lack of appreciation for the centrality of racial residential segregation in forming and sustaining these disparities.

“It is residential segregation, by sorting people into particular neighborhoods or communities on the basis of race, that connects (or fails to connect) residents to good schools, nutritious foods, healthy environments, good paying jobs, and access to health care, clinics, critical amenities and services,” the researchers write.

The Roots of Structural Racism Project was unveiled in June 2021 after several years of investigating the persistence of racial residential segregation across the United States.

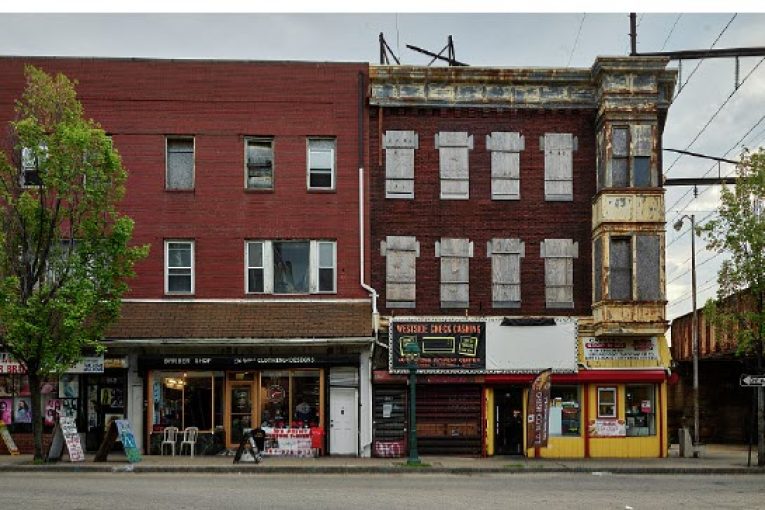

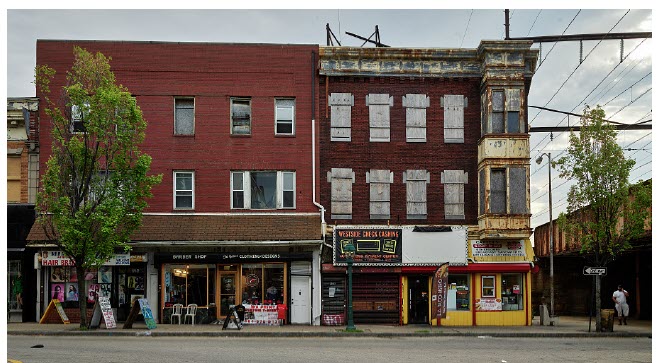

“Aggressive ‘broken windows’ policing practices target racially and economically isolated Black and Brown neighborhoods, while jobs and the tax dollars flow to white communities, leaving crumbling infrastructure, poisonous water, predatory financial institutions, and food deserts behind,” they write.

Racial residential segregation, the report finds, remains the “lynchpin” or “deep root cause” that “sustains systemic racism.”

Moreover, just as Richard Rothstein has pointed out in his work on residential segregation patterns, “unlike school desegregation, the nation never embarked upon a national project to integrate  neighborhoods, let alone declared an unambiguous commitment to that goal. There has never been a Brown v. Board of Education-like decision for housing. Integrating neighborhoods was always going to be more difficult than integrating schools.”

neighborhoods, let alone declared an unambiguous commitment to that goal. There has never been a Brown v. Board of Education-like decision for housing. Integrating neighborhoods was always going to be more difficult than integrating schools.”

The researchers point out that despite the unpopularity of things like busing, students could be relatively easily reassigned to different schools.

“But there is not comparable institution or authority that has the power to compel the integration of neighborhoods, workplaces, or public spaces.”

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 represented the final major legislative achievement of the civil rights movement. It was supposed to prohibit discrimination in housing on the basis of race.

“It began to break down barriers to integration by prohibiting discrimination, but was comparatively weak in terms of proactively integrating existing segregated communities,” they write. “Nonetheless, following the passage of the federal Fair Housing Act in 1968, residential integration increased significantly between 1970 and 1980, to such an extent that many reasonable observers felt that the residential patterns established in the early and middle decades of the twentieth century might actually fade away in time.”

That hasn’t happened.

Instead, they find “these encouraging observations turned out not to reflect the actual dynamics of what was occurring. In most regions, segregation was in fact increasing.”

Among the key findings was the national segregation report which startlingly finds that racial residential segregation has actually increased in recent decades.

Out of every metropolitan region in the United States with more than 200,000 residents, 81 percent (169 out of 209) were actually found to be more segregated as of 2019 than they were in 1990.

The shift of segregation is out of the south and into places like the industrial Midwest. The report found, “Rustbelt cities of the industrial Midwest and mid-Atlantic disproportionately make up the top 10 most segregated cities list, which includes Detroit, Cleveland, Milwaukee, Philadelphia, and Trenton.”

The report finds, “The most segregated regions are the Midwest and mid-Atlantic, followed by the West Coast.” On the other hand, “Southern states have lower overall levels of segregation, and the Mountain West and Plains states have the least.”

Out of the 113 largest cities examined, “only Colorado Springs, CO and Port St. Lucie, FL qualify as ‘integrated’ under our rubric.”

Not surprisingly, “Neighborhood poverty rates are highest in segregated communities of color (21 percent), which is three times higher than in segregated white neighborhoods (7 percent)”

But integration leads to better outcomes for people of color.

For example, “Black children raised in integrated neighborhoods earn nearly $1,000 more as adults per year, and $4,000 more when raised in white neighborhoods, than those raised in highly segregated communities of color.”

In addition, “Latino children raised in integrated neighborhoods earn $844 more per year as adults, and $5,000 more when raised in white neighborhoods, than those raised in highly segregated communities of color.”

On the other hand, “Household incomes and home values in white neighborhoods are nearly twice as high as those in segregated communities of color.”

Along those lines, there are very clearly impacts of racial segregation on measures such as home ownership.

The report finds, “Homeownership is 77 percent in highly segregated white neighborhoods, 59 percent in well-integrated neighborhoods, but just 46 percent in highly segregated communities of color.”

Policies dating back to the 1930s already are reflected in racial residential patterns today.

The report found “83 percent of neighborhoods that were given poor ratings (or ‘redlined’) in the 1930s by a federal mortgage policy were as of 2010 highly segregated communities of color.”

These have strong impacts on things like political polarization.

“Regions with higher levels of racial residential segregation have higher levels of political polarization, an important implication in the context of gerrymandering and voter suppression,” they note.

—David M. Greenwald reporting