By Christine Phan, Richa Uprety & Victoria Yeo

This report is written by the Covid In-Custody Project — an independent journalism project that partners with the Davis Vanguard to bring reporting on the pandemic in California’s county jails and Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) to the public eye. Visit our website to view and download raw data on cases, testing, releases and vaccinations.

San Quentin faced one of the deadliest coronavirus outbreaks in the California prison system last summer, and was given one of the largest penalties in the state over workplace safety violations, for its failure to prevent the outbreak that led to over 2,200 total confirmed cases and 28 deaths.

Amidst the nationwide surge in coronavirus cases in August 2021, San Quentin reported a new COVID-19 outbreak — four residents tested positive, three being reinfections. San Quentin is located in Marin County, which has the highest vaccination rate in the state — over 73% of the county population is fully vaccinated as of Aug. 10. While 85% of incarcerated residents in San Quentin have been fully vaccinated, less than 60% of the facility’s staff members have reported receiving both doses.

The Prison Policy Initiative reported in December that the COVID-19 infection rate was four times higher in state and federal prisons than in the general population — and twice as deadly. A recent report also found that higher prisoner vaccination rates are strongly associated with higher prior COVID-19 infection rates across prisons, which suggests that direct experience with the harm the virus may have motivated many to get vaccinated. However, the analysis found no relationship between outbreaks among the prison population with staff vaccination rates.

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) publishes vaccination data for the residents and staff of its 35 facilities, which are spread across 19 counties in the state. There are notable disparities in the vaccination rates of incarcerated residents, prison staff, and general county populations, and with the current rise in COVID-19 infections in the CDCR system, it is clear that the virus will continue to linger behind bars unless vaccination rates improve and protocol is followed thoroughly.

Comparing vaccination rates for the community, prison population and staff

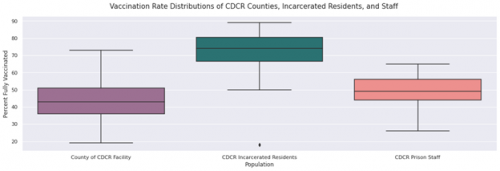

The differences in the vaccination rate distributions between all three of these populations were found to be statistically significant at a 5% level of significance (Ref. 1).

An average of 71.50% of incarcerated residents are fully vaccinated across the 35 CDCR facilities, or 72.95% cumulatively. Excluding an outlier (the Deuel Vocational Institution, which is a short-term facility with 4 out of 22 residents vaccinated), these vaccination rates range from 50.53% to 89%. This is significantly higher than that of the communities that house these facilities, which have an average full vaccination rate of 43.65%. Vaccination rates among CDCR prison staff are slightly higher, but still much lower compared to the incarcerated population, Only about half (49.46%) of prison staff reported to be fully vaccinated on average, or 52.23% cumulatively (Ref. 2). An August report by federal receiver J. Clark Kelso, who oversees California’s prison healthcare, revealed that the disaggregated staff vaccination data shows that only 42% of custody staffers have received a dose. This distinction is especially concerning since custody staffers are in direct contact with incarcerated residents on a daily basis.

The full vaccination among CDCR staff is strongly correlated with the rate of full vaccination in the county of their respective facility, with a correlation coefficient of 0.71 (Ref. 3). This suggests that vaccine uptake amongst the two populations have a strong positive relationship. For example, Sacramento County has an overall full vaccination rate of 52%, and staff members at its two CDCR facilities, Sacramento State Prison and Folsom State Prison, have full vaccination rates of 48% and 55%, respectively.

Differences in vaccination rates for urban and rural counties

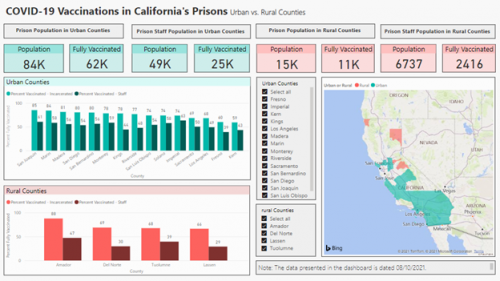

The CDC has noted that there are significant disparities in COVID-19 vaccination rates between urban and rural counties nationwide, reporting in April that 39% of adults in rural areas were vaccinated, compared to 46% of adults in urban settings.

Out of the 19 counties with CDCR facilities, 4 counties (Amador, Del Norte, Lassen, and Tuolumne) are considered rural according to the USDA’s 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. Similar to the general population, the vaccination rates of CDCR prison staff were found to be significantly different in urban versus rural counties. Among urban counties, 52.4% of CDCR prison staff are fully vaccinated on average. In rural counties, an average of only 36.2% of staff members in CDCR facilities are fully vaccinated.

In contrast, the vaccination rates of incarcerated populations are not associated with the vaccination rates of the general county or staff populations – the mean vaccination rates of incarcerated populations in urban versus rural counties were 74.84% and 72.71%, respectively (Ref. 4).

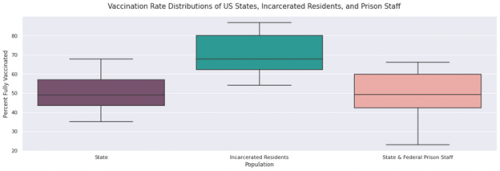

Differences in vaccination rates between prison populations and staff are a nationwide issue

This disparity in vaccination rates between incarcerated residents and prison staff is a nationwide issue. According to data collected by the UCLA COVID Behind Bars Project from 28 states that publish their prison vaccination rates, 70.18% of their incarcerated populations are fully vaccinated as of August 10. Despite having been granted early access to the COVID-19 vaccine as essential workers, prison staff did not get vaccinated at a higher rate than the general populations of their respective states, with only about half having been vaccinated on average (Ref. 5).

In Alabama, the state with the lowest rate of vaccination with just 35% fully vaccinated, 64% of its incarcerated residents are fully vaccinated, compared to only 23% of the state’s prison staff as of August 10.The Alabama Department of Corrections reported more than 200 new cases among inmates on August 18, which is the largest spike in COVID-19 cases in Alabama prisons to date. Alabama governor Kay Ivey has noted that unvaccinated people are driving the surge in cases in her state, but remains firm on her stance against vaccine mandates even as Alabama has declared a state of emergency: “Y’all, I’ve said it several times and I’ll say it again: The state’s not going to have any mandates. It’s up to the individual citizen to take some responsibility, now. Roll up your sleeve and get your shot.”

Vaccine Hesitancy Amongst CDCR Prison Staff

However, leaving the responsibility of vaccination up to the individual citizen has proven to be difficult. The Marshall Project reports prison staff nationwide have been refusing to get vaccinated en masse, with many voicing concerns about long-term side effects, distrust in their prison administration, and support for conspiracy theories. Brian Dawe, a former correctional officer and national director of officer advocacy group One Voice United, noted that a majority of people in law enforcement lean conservative and consume COVID-19 misinformation spread by right-wing media outlets: “A lot of them believe you don’t have to wear masks. That it’s like the flu.”

The high risk of infection that their occupation poses also seems to have lent support to herd immunity arguments. 38% of employees at the California Rehabilitation Center have had COVID-19, including a correctional officer who spoke to CalMatters: “A lot of us have already had COVID and recovered, so we don’t see the point in getting the vaccine. I have the natural antibodies. I get sick every year from something at work, so I figured it’d be a matter of time.”

CDCR prison staff are a primary vector for COVID-19 transmission

On August 3, federal receiver J. Clark Kelso submitted a recommendation for a mandatory COVID-19 vaccination policy as the overseer of California’s prison healthcare. A recent investigation by the California Correctional Health Care Services found CDCR staff to be a primary vector for COVID-19 transmission into CDCR facilities, as contact tracing and genomic sequencing confirmed that at least 50% of all outbreaks between May and July were traced back to employees. The CDCR system regularly tests individuals even if they appear to be asymptomatic, and nearly half of all individuals in the CDCR system who tested positive during this period reported having no symptoms at the time.

A health order issued by the California Department of Public Health on July 26 required correctional agencies to ascertain the vaccination status of staff and for unvaccinated staff to get tested weekly. However, staff may be infected between tests, and even if tests are negative, COVID-19 can be transmitted during the early incubation period. Testing, Kelso affirmed, was no substitute for vaccination.

There have been more than 200 outbreaks in California jails and prisons since the beginning of the pandemic. With the rampant spread of the Delta variant, the proportion of unvaccinated prison staff members poses an even larger risk to public health. “The risk now is grave,” Kelso wrote. “We cannot afford to be lulled by the decline in infections in CDCR, which mirrored the fall in rates in the larger community. That fall in rates is, unfortunately, already a thing of the past. That fire may be dying, but a new one is starting.”

A new vaccine mandate

A new public health order issued on August 5 mandated vaccinations for all medical providers in healthcare settings but excluded correctional settings. On August 19, a new public health order expanded this vaccine mandate to all staff members who are regularly assigned to provide healthcare or healthcare services to incarcerated residents. This includes workers who are not directly involved in delivering health care but could be exposed to COVID-19 in healthcare settings, such as correctional officers, inmate workers, administrative and facilities maintenance staff, and other staff members providing clerical, dietary, laundry, and janitorial services. This expanded mandate, as previously reported by the Covid In-Custody Project, could be a gamechanger. CDCR staff members under this mandate will have until October 14 to comply and get vaccinated.

The California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA) has supported voluntary vaccination efforts among staff members, but is strongly opposed to a vaccine mandate. Citing the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PRLA) in an ongoing court case (Plata v. Newsom), the CCPOA’s representatives argue that the Court lacks the authority to order mandatory vaccination of correctional staff unless prison administrators and state actors acted with “deliberate indifference” and violated the incarcerated residents’ federal right to adequate medical care.

Regardless of the court’s verdict, as long as significant proportions of the prison staff population continue to refuse vaccination, inmates will remain vulnerable in the current wave of outbreaks.

According to the Prison Journalism Project’s San Quentin correspondent Joe Garcia, after fully vaccinated residents in San Quentin’s Alpine unit tested positive within days of each other during the facility’s most recent outbreak, inmates were placed on lockdown while staff members were allowed to travel freely. For residents undergoing frequent testing, a positive COVID-19 result has severe consequences: Those who test positive are immediately quarantined for 10 to 14 days in a building traditionally used as the solitary confinement “hole” for Death Row inmates.

Dr. Anne Spaulding, an associate professor of epidemiology at Emory University and former medical director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, has highlighted the “downstream effects” of unvaccinated prison staff members on the mental health of incarcerated residents. As previously noted in Kelso’s report, correctional officers (known as COs for short) have significantly lower vaccination rates than inmates despite being in close contact with them on a day-to-day basis. “If [the virus] passes from CO to CO, what does that mean with staff shortages? More lockdowns, less programming,” Spaulding said. “It’s going to affect the mental health of those incarcerated, who already have restricted lives.”

Speaking to the Prison Journalism Project, Terry Mackey, a resident in San Quentin’s Alpine unit, expressed his frustration with the selfishness of CDCR staff and officers who are jeopardizing the wellbeing of vulnerable inmates. “This is a controlled environment, and they are the ones controlling it,” he argued. “The only way the virus gets in here is through them.”

“They go home every night and come back,” Mackey continued. “We can’t go home but we’re the ones who keep getting tested, keep getting quarantined and put on lockdown.”

Appendix (Download or view here)

1. See Appendix C for more information regarding our methodology for the significance tests for the differences in rates of full vaccination between incarcerated residents, prison staff, and general county populations of CDCR facilities.

2. See Appendix A for more summary statistics of the full vaccination rates of incarcerated residents, prison staff, and general county populations of CDCR facilities.

3. See Appendix B for more information regarding the correlations between the rates of full vaccination for incarcerated residents, prison staff, and general county populations of CDCR facilities.

4. See Appendix D for more summary statistics and information for the significance tests for the differences in rates of full vaccination for our analysis of CDCR populations in rural versus urban counties.

5. See Appendix E for more summary statistics and information regarding the correlations and significance tests of the rates of full vaccination for our U.S. states analysis.