Preparing to be a father from prison

By Abdur Rahman Malik

There are so many misconceptions about Black fathers. How often has the mother of a child spilled myths about the Black father willfully abandoning them? How often has society cast the narrative that Black men prefer drugs, gangs and money over fatherhood?

I am a Black man. I am a father. And yes, I am in prison. This is my chance to share my truth and diminish the stigma against the Black men who may be absent in their children’s lives.

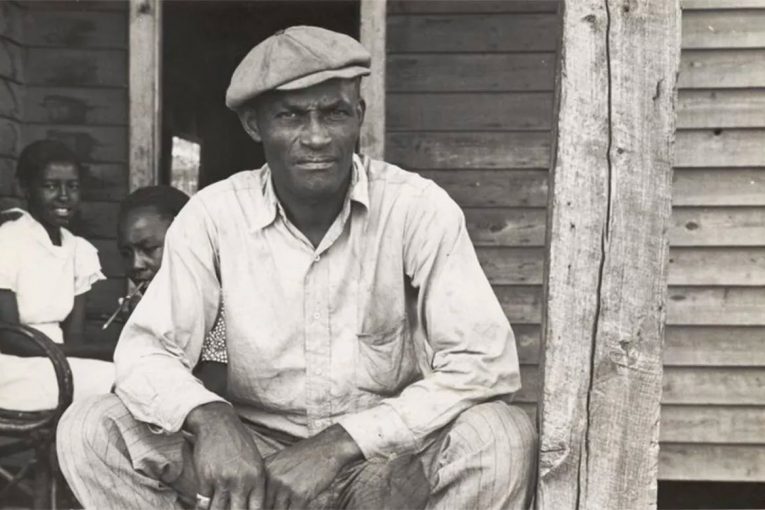

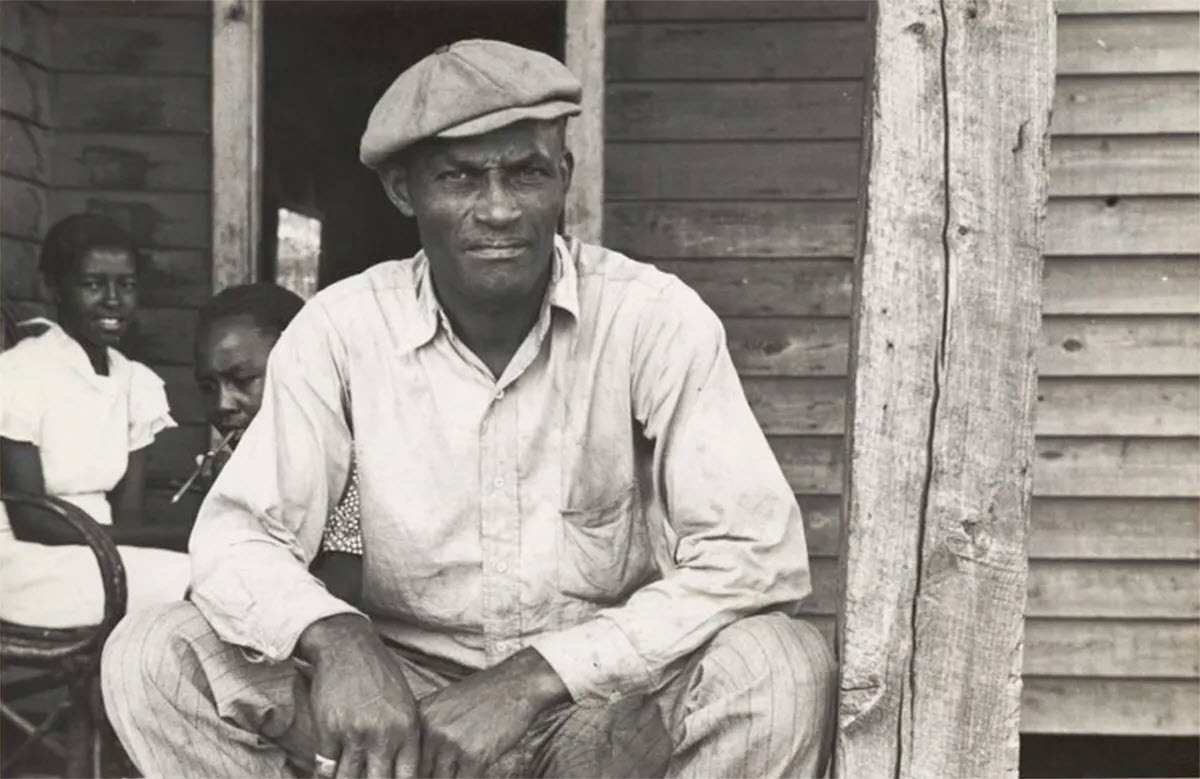

We start off at a disadvantage. Most Black men can trace their origin directly back to slavery. What slavery did to the psyche of the Black man was to permanently associate “work” with oppression. No man wants to willfully endure oppression. Furthermore, no man wants to have his wife or significant other witness him submit to oppression. And no Black man would dare allow his child to witness him be oppressed, weak or submissive.

One may ask, “Be submissive to whom?” Real work does not make one submissive. But to a Black man, the conditions he will face at work are in fact too much of a reminder of slavery. Every Black man is conscious of the attempts of others to prove Black is inferior. Every Black man is primarily motivated to succeed on his own merit. This is why most Black men prefer to be an entrepreneur rather than an  employee.

employee.

Understanding this premise is key before one can scrutinize Black fathers who are incarcerated.

There is a connection between the psychological traumas of slavery and the behaviors of today’s Black men. Even though today’s Black men were not the same shipment of slaves transported to the Americas in 1619, most can trace their origin back to slavery.

Not all will stay confined to shame. Many Black men today have converted that shame into swagger. Our pain has become pride, and this causes us to behave in a way that society has deemed rebellious. What initially began as a rebuke to white supremacy evolved into an attitude of indifference. Black men armored themselves with an attitude of defiance. Not only did we shun racism, we inadvertently shunned responsibility. Our primary focus was to succeed on our own merit and our own way. It’s this thinking which often led to a life of crime.

When Black men decided to take a risk, and rebel against society and social norms, it was only for a chance to claim his portion of the American pie.

Now, as we sit in prison, we have to rethink our position and remove the armor that not only kept us protected but, even worse, isolated us from our children.

I can vividly remember the words of my mother, telling horrifying story after story about my father, how he was abusive and how he liked to fight. Yet, as an innocent child, I recall saying I wanted to be just like my dad.

Even though my father was absent most of my life, it is my position that there can be no suitable substitute for paternal fathers. I was determined to not repeat the cycle. I criticized my father for being absent. I waited until I was 29 years old before I first decided to have children when I was finally ready to start a family. I was present when both my children were born, and I felt different from my father. But there were similarities too.

The reason I am in prison is because I commited a crime. While I’ll agree that this is partially true, I would also agree that like my father, I am a victim in a system predatory to Black men.

The laws of today are made to criminalize the behaviors of Black men to forever keep Massa’s gravy train rolling. I am painfully aware of the situation of the Black men. I am painfully aware of this America we live in. But as a father, how does one approach this duty from prison?

The action I take is consistent with my objective. I want to succeed in all I do.

I want to be honest with my child about who I am and where I am. Yet I don’t want my child associating prison to reuniting with their father like I once naively did. I want to be independent, but, as a prisoner, I am very dependent. These contradictions are enough to cause me to stay absent from my child’s life while in prison, so that I do not give them the impression this is acceptable.

These contradictions are so intense that the best thing I can do for my child is to avoid them while I am weak, avoid them while I am failing.

One can give me a million reasons why it is more important to stay in touch with one’s children even during incarnation, but I disagree. My children are under the age of five and are very smart little people. They are curious about everything. In my opinion they are young enough for me to not interact with them without damaging impact. I intend to begin fathering when I can be present.

If I only become involved when I am able to give them the 100% commitment they deserve, I can represent the father who chooses to return to parenting once released. Keep in mind, my children are young, and I am not planning on being incarcerated longer than 10 years. This decision is difficult yet necessary.

Because I choose not to contact my child while I am in prison, some might conclude that I must not care for them. But my avoidance proves the exact opposite.

It is actually a silent admission that I am failing as a father, I am in a vulnerable situation and I am currently disabled. My absence is my way of acknowledging my children deserve more than what I am able to provide them.

How do I explain to a 3-year-old child that I have to hang up the phone after my allotted time is up? How do I explain to a 3-year old that I’m unable to come see them? How do I respond to all the important questions they will ask without being deceitful? It is a reminder that I am not in control of my life.

Ultimately it is the worst experience between a father and a child, to have them witness their father being oppressed. It is with great pain, great honesty, and shame that I am a father who is a stranger because I respect and value the role that much.

So how do we find a solution that enables Black men to become irreplaceable fathers? We begin by embracing the ugly truth.

As fathers, the welfare of the family needs to be a priority. As fathers, we need to safeguard the family because once we are removed, we let ourselves be replaced. A lot of Black men, who have never been incarcerated, are active fathers and productive citizens in society.

Oppression is real and should never be looked upon as a moot issue. But rather than focusing on obstacles, we need to learn to focus on opportunity.

I’m afraid to fail as a father, but I also am painfully aware that children need fathers. We don’t need to be rich, we don’t need to be strong, we don’t need to be perfect, but we do need to be present. When I leave prison, I am committed to sticking around no matter what because that is the only way our role as fathers become irreplaceable.

Abdur Rahman Malik is a writer from San Diego whose passion is uplifting the Black community. He wrote and published much of his work on PJP while incarcerated in California.

Originally Published by the Prison Journalism Project. Prison Journalism Project trains incarcerated writers to become journalists and publishes their stories. Subscribe to Inside Story to receive exclusive behind-the-scene looks at our best stories, as well as author profiles and other insights.