by E. Self

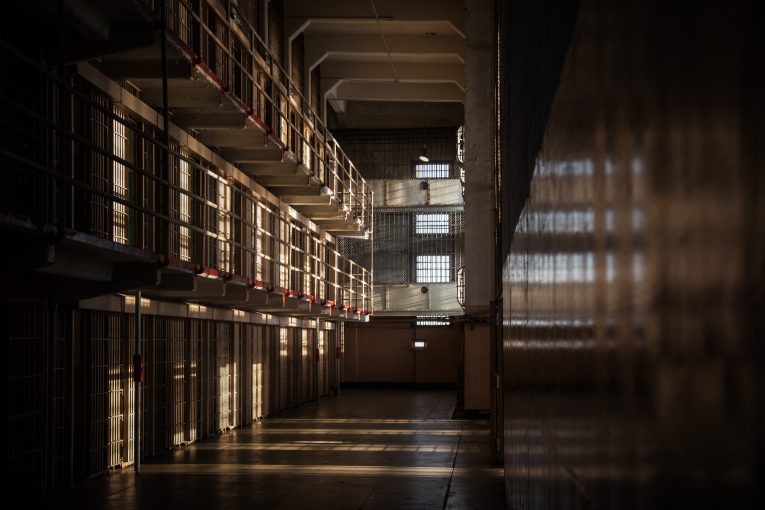

In northeast California is situated the small, rural town of Susanville, where High Desert State Prison can be found. Have you ever wondered how people live in such an environment? We rarely give thought to anything that doesn’t directly impact us; nevertheless, I can assure you the experience is quite different than one may first conceive.

I live in a typical 7×12 foot cell, constructed of cement, with a stainless steel toilet-sink combination, steel desk, steel lockers and bunks. The first thing one notices when entering is how small it is. The second thing is the smell, not of body  odors, but the scents of cement and steel. The last thing you notice, as the steel door closes behind, is how heavy the loneliness settles around you. … It sure isn’t the Hilton, but it is home …

odors, but the scents of cement and steel. The last thing you notice, as the steel door closes behind, is how heavy the loneliness settles around you. … It sure isn’t the Hilton, but it is home …

Along the back wall, between the lockers and bunk beds, is a desk and stool attached to the wall. Above the desk is the grandest thing of all: the window. Recessed into the wall, a long, skinny vertical slit to the outside, the window offers the only warmth from an otherwise gloomy environment, delivering a beautiful scenic landscape of snowcapped, slate-gray mountains that protrude into the soft white clouds that hang lazily in an azure sky. The sunshine illuminates the contours of the rolling hills—at first obscured by the electric fence—that lead to the mountains’ base … White birds, black birds, and occasional brown birds soar freely in the sky or run along on the ground chasing one another.

Looking outside the window you can feel the freedom, whereas, by comparison, inside the cell the feeling is oppressive, whether through nature or by design. Though small as it is, that glimpse to the outside world allows the burden to be lifted from your shoulders, providing one the means to ski the slope of the mountains; freely soar with the birds; or race along the dirt road between the window and the fence, believing, if not knowing, that you can generate enough speed to hurdle that 15-foot electrified barrier to freedom, if only in one’s head. All the same, for that brief amount of time one is free, free from the oppressive nature of prison life, where one’s constitutional rights are worth no more than the single-ply roll of toilet paper issued each week.

The difference between believing what living in prison is like, compared to knowing, is the experience. Television cannot capture or emulate that onerous feeling of having to endure, day after day, year after year, what it’s like to reside within a cell where you become familiar with every scratch and imperfection. Believing is one thing, experiencing quite another, where experience cannot be replicated without, well, experiencing.

Republished from “Perspectives from the Cell Block: An Anthology of Prisoner Writings” – edited by Joan Parkin in collaboration with incarcerated people from Mule Creek State Prison.