By David M. Greenwald

Executive Editor

Davis, CA – I don’t know where the notion came from that the city of Davis could not run a revenue measure alongside a Measure J vote.

The city actually did this to a good amount of success in June 2018.

The city actually ran two tax measures concurrently along with the second version of Nishi.

The city actually ran two tax measures concurrently along with the second version of Nishi.

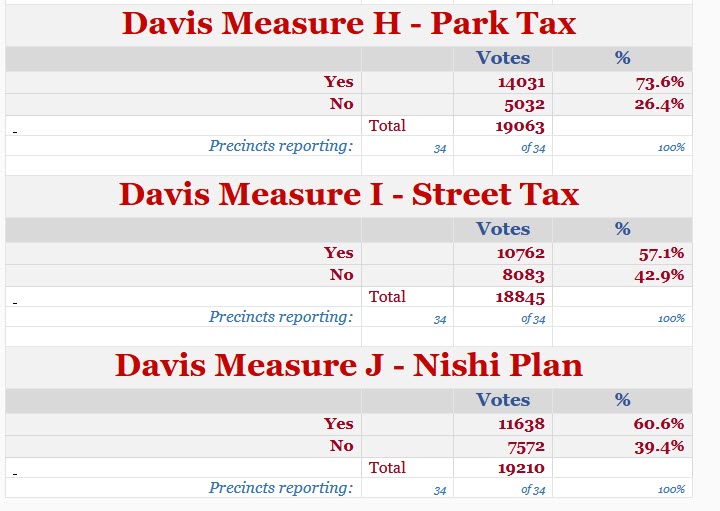

The Park Tax was a straight renewal and won at nearly a three to one margin with 73.6 percent of the vote. The Street Parcel Tax “failed” in the sense that it fell short of the two-thirds needed for passage. But it still garnered 57% yes votes.

And finally, the first ever successful Measure J project was on the ballot with Nishi receiving more than 60 percent of the vote.

I know the city is really touchy about getting the revenue measures passed, but I think the lesson from 2018 is pretty clear—there is nothing that should prevent the city from running a revenue measure alongside a Measure J vote.

Even the “failed” Measure I still got a majority of voters to approve it. And 57 percent is a strong majority under most conditions.

The city should absolutely avoid a special tax that would require a two-thirds vote. Had they done that, the street tax would have easily passed.

I would also argue that I did not believe that the city ran a sufficient campaign on Measure I. They really needed to hire a campaign consultant and run it along the lines of how the school district runs a parcel tax.

The city needed to engage the public better on the issue of roads and the overall fiscal health of the city, which poll after poll shows the public believes is far better than it actually is.

However, if the city council puts a general tax on the ballot in November 202—which they are able to do since it’s a council election—they will only need 50 percent, which is a much lower threshold.

The Council Should Not Put Simultaneous Measure J Votes on the Ballot

One thing the council should avoid is two Measure J votes simultaneously. I have had this question come up several times in the past week.

The answer is no: don’t do it, if you want a project to pass.

There are several reasons for this.

The main one is that you end up splitting the vote of those who want one but not two.

Basically all of the internal polling I have seen shows that there is still a 35 to 40 percent of the vote that is an almost automatic no—they are going to always oppose housing projects.

This starting point is also why it’s so imperative to run housing projects in high turnout elections. This is actually the opposite of how the school district should run their parcel taxes.

We have three pools of voters—the 35 to 40 percent always no, a much smaller number of always yeses, and then a middle ground of voters who favor one project, but not both.

We don’t have exact data on how many that is. But let’s assume it is somewhat sizable. Best case scenario, that puts your margin for error at almost zero. You have to maximize your vote while at the same time getting just enough of that middle tier to push you over the top.

But there’s a good chance that, by splitting that middle vote, you end up with neither project passing.

Opponents of the projects can attack both and simultaneously argue that the city is growing too fast and developing too much. It hands a lot of ammunition to an opposition that really doesn’t need a lot—as we have seen—to defeat a project.

I do believe in the end that we need all of the housing projects that have currently been proposed. It is pretty clear that the city is not going to be able to meet its housing obligations without having the approval of at least two, probably three projects by 2028.

And if that’s the case, the city needs to maximize their chances of getting approvals by putting them on the ballot sequentially rather than concurrently.

So, at the end of the day, the city should be able to put both a Measure J vote and a revenue Measure on the ballot in November 2024. That would maximize the chance of getting a project passed, and the experience of 2018 shows that they can do that without jeopardizing the revenue Measure.

The city council should not attempt to do more than one Measure J project on the ballot at once and again should stick to elections that are likely to have a fair amount of turnout. With council elections shifting to November, that means the two targets should be November 2024 and November 2026.

In order for the project to count in the RHNA calculations, a Measure J vote is going to have to be passed prior to 2028.

As the saying goes if there is a will there is a way. This is especially relevant regarding putting a revenue measure and housing development on the ballot in a Presidential election year.

Our city streets are in urgent need of repair. A few years ago I ran over a big pothole near my sister’s house in Central Davis and got a flat tire. The tow truck driver told me that he sees a lot of flat tires as a result of Davis potholes.

“I would also argue that I did not believe that the city ran a sufficient campaign on Measure I.”

This is an argument in conflict with your thesis.

Of course you are missing the point. Vaitla wants dense infill instead of peripheral development. His tax only proposition might be sincere or it could be a smokescreen that helps him drive towards what he wants to do. However, there is a certain logic in his approach because in Davis, unlike most places due to Measure J, infill is easier to do than peripheral development. While I disagree with Vaitla’s approach, and it remains to be seen if Neville will change the dynamics on the CC, I understand Vaitla’s logic. It will be interesting to see if he can execute his plan and get many of the infill projects waiting to be processed approved.

Of course you are correct that Davis is unlikely to hit its quotas under his approach but I don’t think that is Vaitla’s major concern. I think his major concern is at the intersection of the path of least resistance and carbon footprint.

I think Vaitla is sincere in wanting to build infill first, but I also think he recognizes that peripheral is inevitable.

Measure J tilts the trade off slightly towards infill, but infill remains more expensive and as we saw with University Commons, still not easy to get approved.

I question whether high density infill is going to fill the city’s need for housing for families. It could serve as workforce housing for people entering the workforce, but cost is going to be a problem and affordable housing in infill is fraught.

In addition, there is a question to as to how much infill we can actually build. The current housing element, also takes huge swaths of infill out of commission for future RHNA’s. For instance, the downtown is now zoned for 1000 housing units, that means that in 2028, the city can’t use the downtown at all unless they somehow actually build more than 1000 units (not gonna happen).

In short, time and state guidelines are going to push things in the direction I’m suggesting, the only question is how soon the council gets on board.

Again, every city is going to face this same situation – especially the vast population centers along the coast.

How do you envision the state winning its war against these vast population centers? Especially in regard to Affordable housing requirements?

Despite having the “law” on their side, they have no chance of winning that war. There are too many factors working against them, and the failure will be far too massive for them to do anything about it – even if they could.

Can’t imagine that Rob Bonta is going to be increasingly-eager to take this on, either – since he’s running for governor.

And for that matter, I suspect that the ongoing challenges against the state will eventually have an impact, as well. For example, the manner in which the state came up with the RHNA numbers in the first place. (Ask the state auditor about that.)

“Again, every city is going to face this same situation – especially the vast population centers along the coast.”

How does that change anything?

David: I think you already know the answer to that, and I’ve probably provided it more than once as well.

The state is not going to have the will, resources or even the ability to force cities to comply in mass. For that matter, neither do cities themselves. And that will ultimately include Davis.

And if cities which aren’t expanding outward (e.g., the vast population centers near the coast) also can’t “count” unbuilt sites for future RHNA rounds, this is going to ensure mass failure.

I suspect that even state officials themselves know this, while they continue trying to spin-off more laws. It’s not unlike the earlier “war on drugs”, in terms of effectiveness.

But it will be amusing to watch – statewide. Just wait and see.

So as I said on Friday, your response to all this is the city of Davis should not attempt to zone and build the housing required by the state, because IN YOUR VIEW, the state can’t or won’t enforce that requirement.

In my view, the city should address the current round of RHNA targets. Which is exactly what they’re doing.

IN YOUR VIEW, the city should pursue sprawl now to address some unknown future. Despite the fact that no other city in California is pursuing sprawl for the purpose of addressing current rounds, let alone future rounds.

I realize that some cities may have been pursuing sprawl even in the absence of those targets (“business as usual”), but certainly not the vast population centers along the coast.

And this belief is ultimately the reason that it doesn’t matter if the council attempts to “strategize” in the manner you’re suggesting.

Ultimately, opponents will point the following out, regardless:

The council might as well put all half-dozen of them on the ballot, simultaneously. Because that’s what they’re pushing, anyway. (I like to round-them off to a half-dozen.)

They’re not going to be able to successfully argue that it’s “one and done”. For sure, opponents will point this out – repeatedly.

By placing their “favorite” one on the ballot now, they’re open to allegations of favoritism. If I was one of the developers who “wasn’t selected” (but perhaps submitted my proposal “earlier” than the favored one), I’d be exploring ways to sue the city.

And by the way, suggesting that the council “strategize” to get proposals passed is the very reason that Measure J exists.

And this will also be pointed out, if the council starts manipulating proposals and going back on what they already proclaimed.

You might be making it easier for opponents, with your suggestions. Thanks?

“And by the way, suggesting that the council “strategize” to get proposals passed is the very reason that Measure J exists.”

The very fact that the council has barely strategized at all over the last 20 to 25 years is the reason why we are in the mess we are in and why Measure J may not exist much longer.

There is no “mess”.

First off, Davis (unlike many other cities) has consistently “met” its RHNA targets.

Secondly (and we go through this in every article), there’s vast population centers along the coast which are subject to these same type of “targets”, but which aren’t expanding outward. So until someone can explain how that can occur, singling-out Davis in this manner in support of some peripheral proposal isn’t honest.

And if voters are “forced” to approve peripheral proposals indefinitely, sooner-or-later Measure J will be challenged (or so you claim). Why have Measure J if there’s no real choice but to vote “yes” on proposals in the first place? Explain what purpose it’s serving, if that’s the case.

And if Measure J is overturned, you can be sure that it wouldn’t be the “end of the story”. If anything, it would be a new beginning.

In any case, evidence shows that the state’s efforts are going to fail – statewide. It will take a few years for this to become increasingly-obvious.

But as previously pointed-out, the state cannot force annexations of farmland outside of cities, regardless. Their focus is on cities, themselves.

It seems far more likely that voters might approve a proposal, only to see the developer pursue the “builder’s remedy” – regardless of baseline features or development agreements. Davis already has one developer essentially threatening to do so – Measure J or not. The one that advertises on this very blog!

It’s not a war. The state is trying to reduce the housing cost and availability burden for California residents.

The state doesn’t control the market factors and isn’t presently providing direct funding, so the amount of housing that will be built is out of their control. So, what will happen if/when the housing numbers come in as we get toward the next housing cycle and there’s a shortfall?

What will happen is that the state housing department, which has been getting formal feedback from the regional agencies, may modify the RHNA determination process and may change their enforcement actions. There is going to be an evaluation and a report by HCD with recommended changes.

https://scag.ca.gov/rhna

The feedback they are getting would require action by the legislature as well as by the regulatory agencies.

Here is an example of feedback one regional agency (SCAG = Southern California Association of Governments) has provided to the state department of housing.

https://scag.ca.gov/sites/main/files/file-attachments/23-0512_rhna_reform_draft_staff_recommendations.pdf

The present goal is to reduce the obstacles that local governments had erected to housing. That means zoning changes are needed. Without specific numerical goals, the cities and counties would not have any idea what was required of them. Even if those housing numbers are reduced for future cycles, removing the barriers to development is a key part of the strategy for getting more housing built in places where it’s needed.

Changing the zoning is absolutely necessary in order to get more housing built and get it built equitably. That has to happen at the local level, and communities won’t do it unless they have to. So even if the housing that gets built doesn’t meet the HCD numbers, this part of the process is essential.

It’s definitely a war. As you noted yourself, communities are resistant to this (to say the least). And as always, the Affordable component (which is supposedly the “justification” for this in the first place) is particularly-prone to failure.

In any case, here’s a recent, detailed article that I just found regarding the “feedback” process:

https://48hills.org/2023/05/the-state-housing-secrecy-just-keeps-getting-worse-and-worse/

This does not instill confidence for anyone – other than the development activists. Reminds me of “public input” meetings, in which the decisions have already been made.

As usual you exaggerate. There are literally no guns or other weapons involved. Exaggerating is a highly typical tactic of “no housing” advocates like you Ron.

That’s your only definition of “war”?

What about the “war on poverty”, the “war on drugs”, etc.?

The state is literally threatening its own cities.

And even worse – the state is (purposefully?) setting up cities to fail its contrived “test” to avoid war.

In this case, the “bully” already knows that its “victims” won’t be able to come up with “lunch money”. Apparently, the bully just wants to see its victims dance.

All this reflection only confirms my thesis that the city council understand very well that the no voters for development will probably also vote no on a tax. Taken separately, maybe they won’t. But when you get those mean no voters going, they like to vote no on everything an everybody. And harkening to the past election with Nishi and taxes, that was then. This is now. I’m not saying it isn’t doable, but the bandwidth for this volunteer city council isn’t there, at least not now. Realistically, they are taking the path that is real to them.

I think a lot of people might see the mean voters are the “yes” on everything voters. The voters who always vote yes on taxes even though they often don’t have to pay the taxes themselves, as in parcel taxes.