By Randall Morris

It is early May, 2023, and you are about to render a guess as to the actual retail price of an 8oz. jar of Folgers Classic Roast Instant Coffee. The collective shouts from the audience support your gut feeling that the right price is about six and a half so you confidently shout out “$6.48”! The gameshow host then pauses a second to build anticipation before removing the blinder to reveal the retail price of… $22. Wait,…What?! Really?

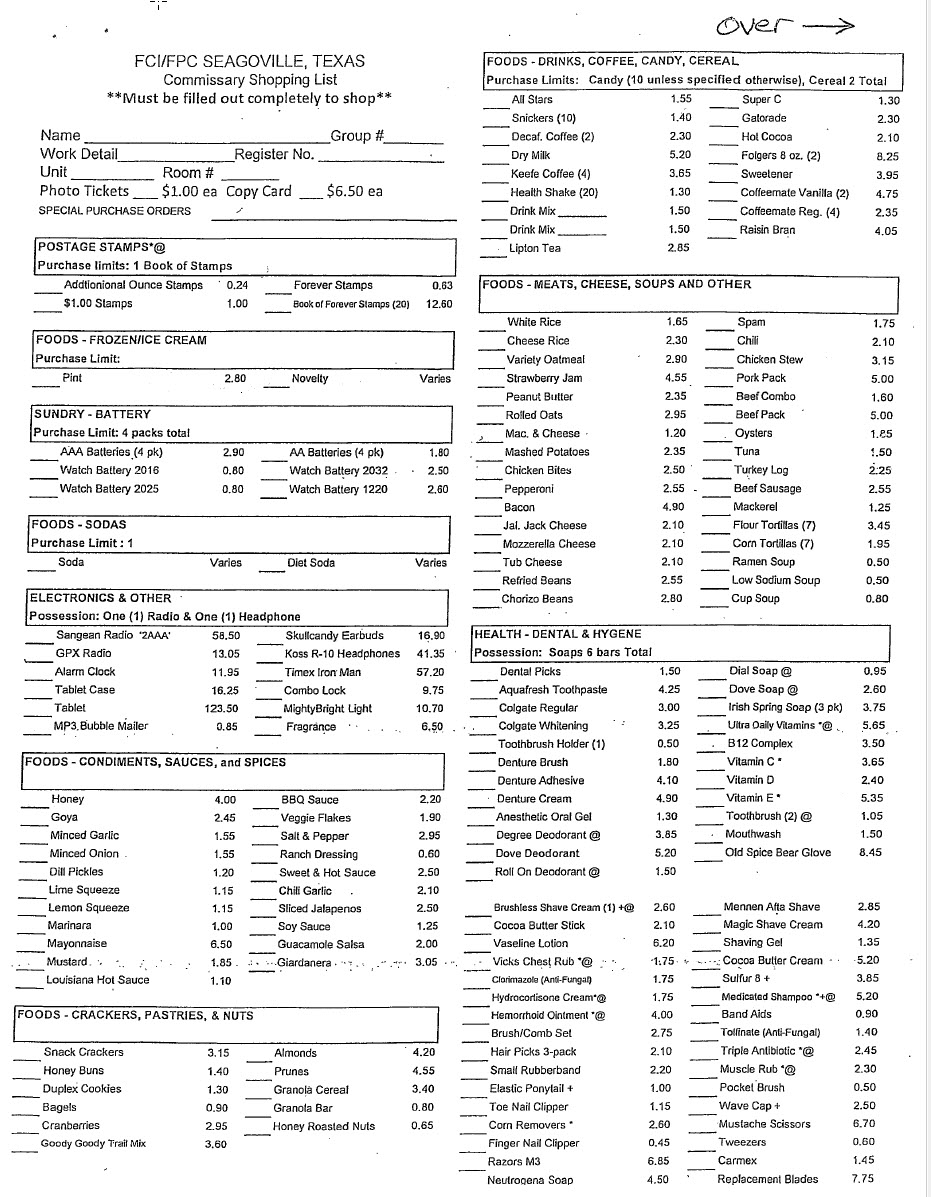

That’s right. That 8oz. jar of coffee was $22 at the Miller County Detention Center in Benton, Arkansas, where I was held for several years before my recent transfer to the Federal Bureau of Prisons (“BOP”) where it currently retails for $8.25. The current Walmart retail price of $6.48 looks like a wholesale price in comparison to both.

Predatory and exploitive commissary retail margins are nothing new within the “captive” market of U.S. county jails and prisons due to the lack of transparency, government regulation and media attention. And antitrust laws are not applied to this market despite the relative ease with which these violations can be proven.

What is new is that the recent adjustments for inflation that have been added to the bloated commissary  pricing that has always existed has created the most extreme pricing ever seen.

pricing that has always existed has created the most extreme pricing ever seen.

From my perspective as a federal inmate, it was great to see the USA Today News article titled “Inflation Hitting Hard in Prisons” by Alex Arriaga and The Marshall Project (5/3/23 – vol. 41, No. 162).

However, as that article did not go far enough, I will enumerate below the deeper points that, if reported, would make that article complete.

- The USA Today article only mentioned state prisons. County jails, where most inmates begin and where they typically languish from one to four years (five years in my case), and federal prisons were not included. Why is this important? The article presented the current price of 32 cents for instant ramen noodles at the Illinois State Prison as an example of a high commissary price attributed to inflation. That same product is currently 50 cents at the federal prison in Seagoville, TX and it is currently 90 cents to $1.25 in county jails ($1.25 at the Miller County Detention Center in Benton, Arkansas).

- According to the article, “Two out of Three people behind bars work while incarcerated an ACLU analysis found.” It went on to state that “most prison jobs involve maintaining prison operations” and, “These are often low paid or unpaid positions.” The word “often” in that quote is misleading because most all paying prison jobs are low or token paying jobs. Furthermore, there are very few paying jobs in state and federal prisons compared to the total inmate populations and very seldom are there paying jobs in county jails.

The U.S. Constitution, as well as over a dozen state constitutions, permits prison inmate slavery and shockingly low wages through the wording of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution that prohibits slavery “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” States like Arkansas take this loophole to the extreme by requiring all Arkansas State inmates to labor without pay unless medically excused which results in an almost one hundred percent (100%) employment statistic. And for this unpaid labor, Arkansas doesn’t have the decency to lower its prison commissary margins like the military does with its capped commissary markup for the service members. These paper employment numbers from states like Arkansas have undoubtedly been fed into the ACLU’s “Two out of Three” inmate employment analysis causing perception distortion.

At FCI Seagoville, where I am, most of the one thousand eight hundred (1,800) federal inmates are unemployed because, like at most prisons, there are simply not very many paying or volunteer jobs. And those federal inmates that do have paying jobs earn only $20 to $60 per month, and that is before federal withholding and “IFRP” are deducted. (See #5 below for “IFRP”).

- The article did not ask the burning question: For those prisoners that do have paying jobs, why aren’t periodic adjustments to wages made to offset inflation as with the government COLA – Cost of Living Adjustment?

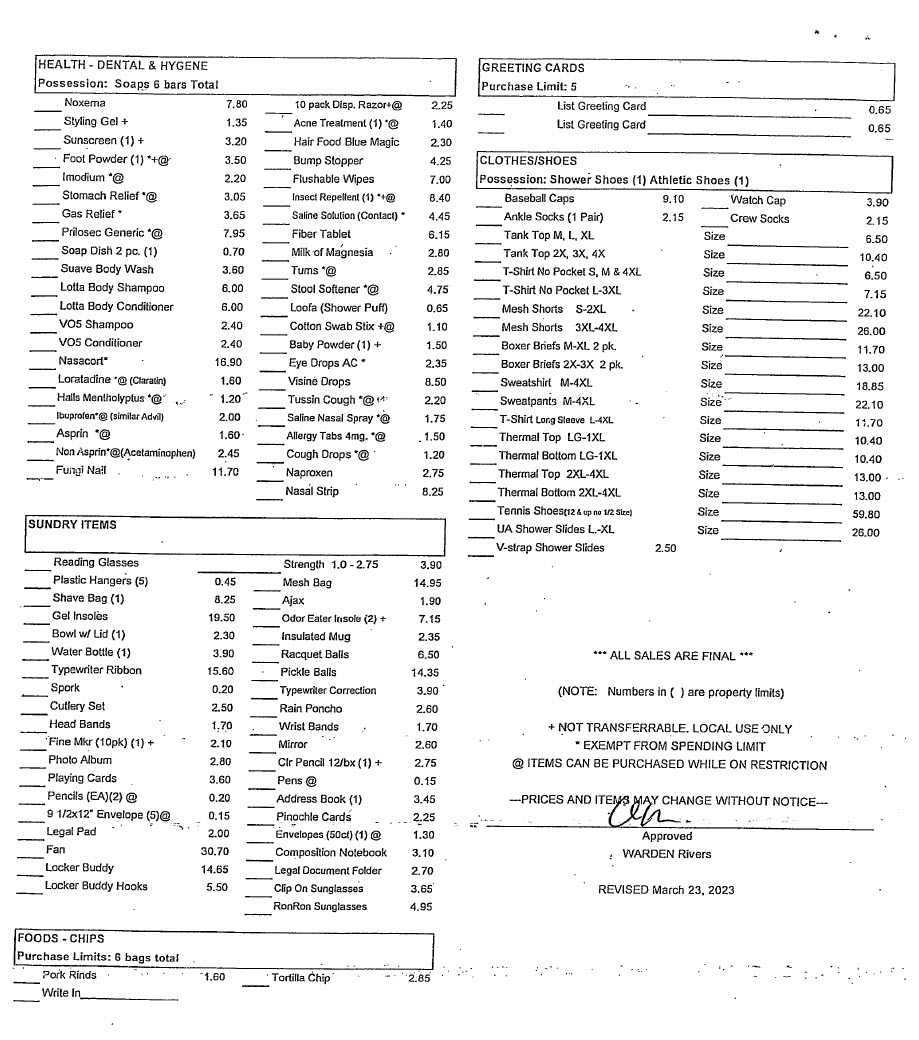

- In addition to excessively high commissary prices and lack of wage adjustments, there is another factor that needs illumination: The monthly inmate commissary spending limits that are imposed on state and federal inmates that have not been adjusted for inflation. These frozen spending limits act as a secondary inflation for those that are lucky enough to receive outside monetary support.

Over the last two years at FCI Seagoville, the prison commissary prices for flour tortillas have increased fifty-three percent (53%), coffee twenty- seven percent (27%), Degree deodorant sixty percent (60%), plain bagels sixty-four percent (64%), mayonnaise one hundred thirteen percent (113%), V05 shampoo sixty-six percent (66%), and Ramen noodles sixty-seven percent (67%).

The prison wages and commissary spending limits have not increased during that time.

- And lastly, if the discussion will include the BOP, this discussion would not be complete without including the devastating impact of the newly proposed changes to BOP 28 CFR Part 545 – “Inmate Financial Responsibility Program” or “IFRP” which states its purpose as “To encourage federal inmates…to pay financial obligations and to support federal inmates in developing financial planning skills.” (See Federal Register Vol. 88, No. 6 [public comment on the proposed changes closed on 3/13/2023]). It further states that “Inmate participation in the IFRP is voluntary.”

In reality, the IFRP is being used to extort steep monthly payments of seventy-five percent (75%) of money sent to inmates from the outside to pay toward any court ordered restitution and fines through the threat of a reduced commissary spending limit to twenty-five dollars ($25) per month, loss of earned early release for completion of the BOP drug treatment program (RDAP), loss of First Step Act Earned credits, downgrade in housing, etc. for non-participation.

Due to these punitive threats, it can be fairly stated that the IFRP is not voluntary. Furthermore, it is forcing outside family to pay more money to ensure that their incarcerated loved ones have enough money. And although the IFRP rules state that reasonable inmate expenses are to be considered when the BOP decides how much money should be deducted and put towards IFRP, the truth is that an algorithm simply spits out a dollar amount that is based entirely on the gross amount that the inmate received and without any discussion or deductions for reasonable expenses, i.e., college correspondence courses, tuition, books, subscriptions, writing/typing supplies, postage, etc. The inmate is then compelled to sign a contract agreeing to this arbitrary monthly IFRP payment or the inmate is subject to the aforementioned penalties for “refusal” of this “voluntary” program.

As one can see, the prison commissary issues are numerous, extreme and underreported.

Randall Morris is incarcerated at Federal Correctional Institution in Seagoville, TX.

Randall Morris is incarcerated at Federal Correctional Institution in Seagoville, TX.