As censorship and harassment spread across South Carolina, teachers are finding allies in their communities.

By Paul Bowers

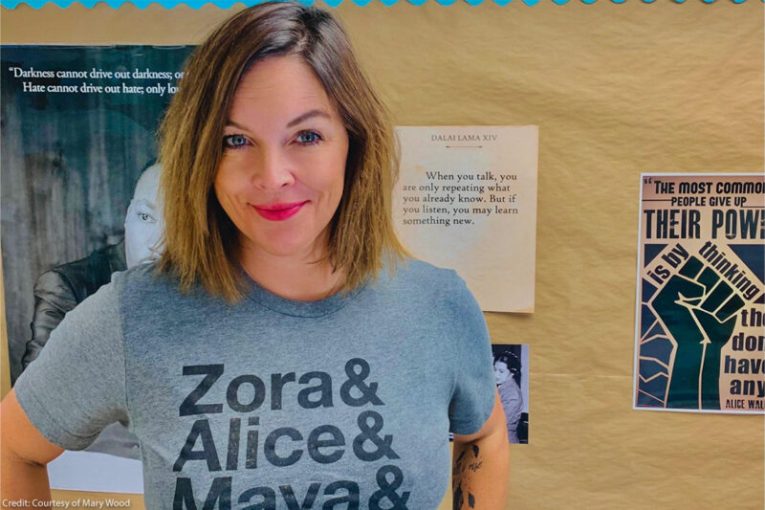

In the past year, Mary Wood has gone through an ordeal that’s increasingly familiar to teachers, librarians, and school administrators across the country: She is being targeted by activists who want to censor what books are in libraries and what discussions happen in classrooms.

Mary is an English teacher at Chapin High School in Chapin, South Carolina. As originally reported in The State, she assigned Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “Between the World and Me,” a nonfiction book about the Black experience in the United States, as part of a lesson plan on research and argumentation in her advanced placement class. District officials ordered her to stop teaching the book. They alleged that it violated a state budget proviso that forbids a broad range of subject matter involving race and history.

“Between the World and Me” was published in 2015 as an open letter by Coates to his son, reflecting on currents of hope and despair in the struggle for racial justice in the United States. It won the National Book Award for Nonfiction, whose judges said, “Incorporating history and personal memoir, Coates has succeeded in creating an essential text for any thinking American today.”

Coates’ book has been the target of censorship campaigns across the country where book banners are targeting books by and about people of color. In the first half of the 2022-2023 school year, 30 percent of the titles banned were about race, racism, or featured characters of color, according to PEN America. South Carolina is one of five states where book bans have been the most prevalent, alongside Texas, Florida, Missouri, and Utah.

Mary Wood has found herself right in the middle of this nationwide attack on the right to learn and the freedom to read.

The following is an interview with Mary about her experience. It has been edited for length and clarity. For more information about how you can fight back against the wave of school censorship in South Carolina, join the Freedom to Read South Carolina coalition and visit our Students’ Rights page. You can learn more about how the ACLU is defending our right to learn nationwide here.

ACLU: You assigned “Between the World and Me” to an Advanced Placement (AP) Language Arts class. Tell me about that.

Mary Wood: So the lesson plan began with a couple of videos to provide background information about the topic. It discussed racism, redlining, and access to education, which are all topics that Ta-Nehisi Coates covers in his [book]. That was to prepare students. Then I provided a lesson on annotation of texts according to AP standards and expectations, things which should be helpful for them on their essay and in collegiate-level reading and writing. Finally, I provided them with information about different themes that the book touches on, under the umbrella of the Black experience in modern America.

The idea was for them to read the book, identify quotes from the text that covered those different themes, select a theme for themselves, and then research what Coates said about that theme on their own to determine whether or not what he was stating held water — if they agreed with it, if it was valid. The goal was for them to look at a variety of texts from a variety of sources: “Here is an argument. Is it valid?”

We were listening along with Coates’ Audible recitation of the book, and they were to be annotating as they went along. We didn’t get that far — we didn’t get to the part where they do research — because we didn’t finish the book.

ACLU: You and your teaching of this book have been a topic of discussion now at a few school board meetings. At one of the recent meetings, several people noticed that Ta-Nehisi Coates himself showed up and sat with you in the boardroom. Tell me a little bit about how that came about and what it meant to you for him to be there.

Mary Wood: I had given an interview on “The Mehdi Hasan Show,” and Ta-Nehisi’s publicist reached out and asked for my information, and he called. He wanted to talk about what had happened, and he was concerned not for his book specifically, but for censorship in general. He offered that support, and I thought it was a really special and notable thing for him to do.

ACLU: You’ve been personally the subject of all kinds of public comments, from vitriol on the one hand to deep support on the other, and it’s all happened in the town where you grew up. What have you learned about your community while going through this?

Mary Wood: It’s not as staunch as I perhaps thought. I think it’s really easy to assume that the loudest voices are the only voices, but I have seen a different side of that. I saw teachers show up. Teachers in general are afraid to speak out, but the ones who did spoke out in ways that haven’t really happened before. I think that this is important, and it was important to them, so much that they were willing to come out of their comfort zones.

ACLU: How are you feeling about the upcoming school year?

Mary Wood: I’m feeling very anxious, honestly. I don’t know what to expect. The [July 17] board meeting had a wonderful showing of support, not just for me but for educators in general and for the material that we teach. Trusting us is really helpful.

If you look at the board meeting before that, there was a lot of discussion about me deserving to be terminated. One person made a comment that they’ll be keeping their eyes on us. Despite all the kind words and support from the last school board meeting, that one really sticks with you. It stuck with me anyway.

I don’t know what’s going to happen. I don’t know how I’m going to be received by parents and students. I think it’s unfortunate how I’m definitely considering every single thing that I do — and not that I wouldn’t before, but you’re on this heightened alert.

ACLU: This is a challenge that a lot of teachers are facing right now. Is there any advice you’d give to teachers, librarians, anybody who finds themselves in the spotlight like you’ve been?

Mary Wood: I would say it’s important to really look at the policies that are in place. Even though from my perspective I did not break a single policy, I was still said to have. I think it’s really important to not acquiesce just because somebody says something. That doesn’t mean that it’s true.

I would say be bold and don’t back down. Look for resources. Maybe I’m fortunate enough that this story did make national headlines so that it drew attention from the likes of Ta-Nehisi Coates, from the National Education Association, from other people who are really valuable resources. If I could do anything, it would be to find a way to bring this all together.

Paul Bowers, Communications Director, ACLU of South Carolina. This article was originally published by the ACLU of South Carolina.