It is difficult to know exactly what will arise out of the current national discussion about police tactics, but one thing is almost certain – the national debate that started in Ferguson will result in most police departments within the next few years adopting body worn camera policies. The technology will not only allow for transparency and accountability, but it could also help people who have acted within the law and departmental guidelines to have a viable defense.

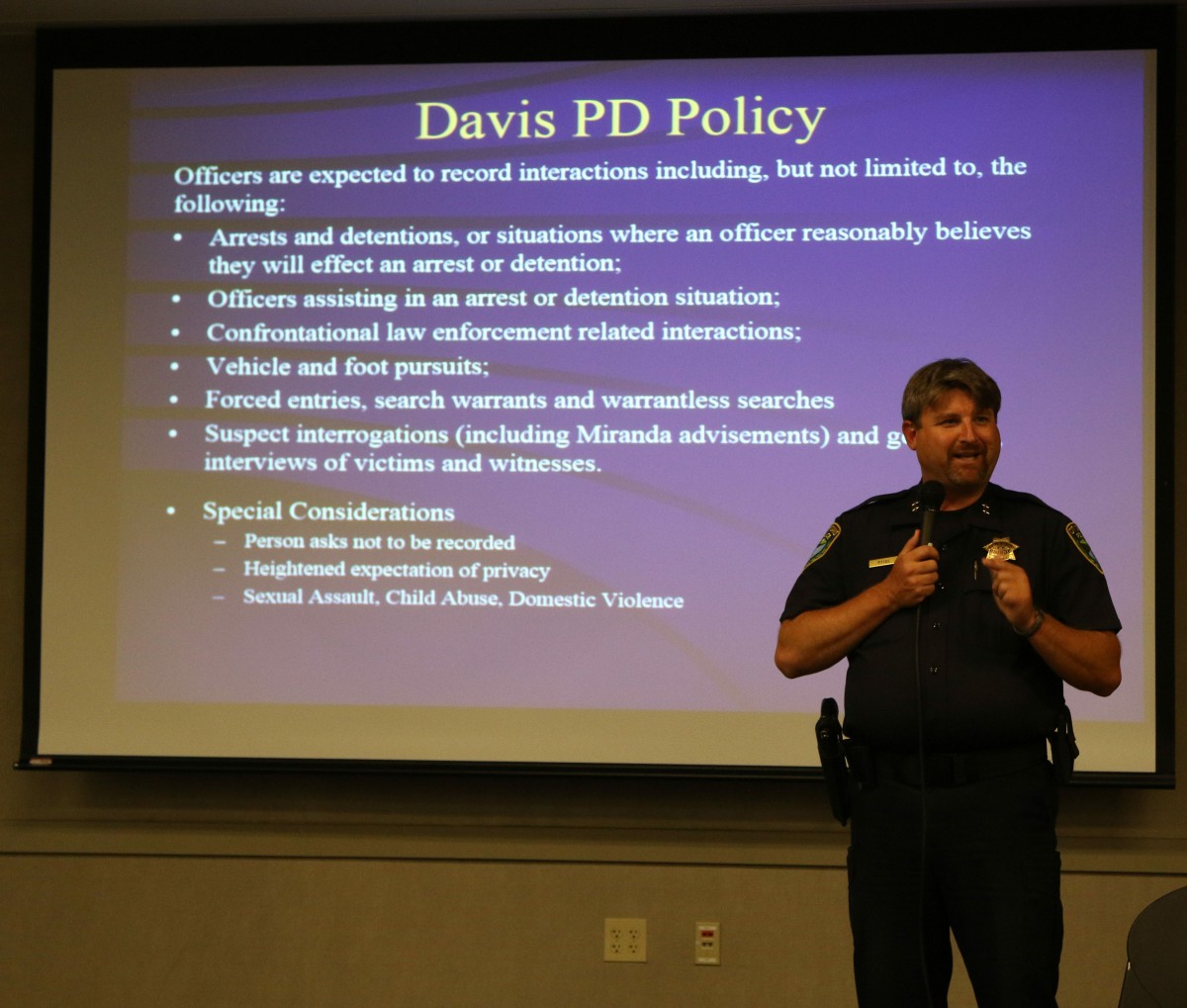

As we have reported in the last two months, Davis is moving towards developing its own policy – and while we commend the police department for taking on this important issue, the policy as presented to the community thus far has some flaws.

One problem is that the current proposed guidelines for release are so high as to really provide no protection to the public. The public will have not have these recordings available. Under the Public Records Act, police records are covered under all sorts of exemptions that preclude their release. As such, the only times when they would be available would be in criminal or civil proceedings where their release would come during the discovery process.

As such matters are rare, we would effectively have no means to view video in most cases. Here are a few examples. The pepper spray incident was widely videoed on phones, but if the incident had occurred in the city of Davis and the public had not videoed it, we would have never seen the incident. Why? Because the DA never prosecuted the officers and the lawsuit was settled well before discovery occurred.

Likewise, the 2012 Tasering of Jerome Wren and Tatiana Bush, that resulted in the firing of a Davis police officer, was never criminally charged, never reached a civil suit and thus a video would never have been released to the public to view.

Furthermore, there is the 2009 shooting death of Luis Gutierrez. The DA declined to file charges against the officers. The matter did eventually get to Federal Court for a civil suit in 2012. So, if there had been a video, for three years the public would not have been able to view that highly contested case.

That is certainly what the police want, but that doesn’t give us true transparency. Civil suits are messy and costly. We need a more certain way that critical incidents can get to the public than by forcing victims of police incidents to sue and go through the discovery process – that could ironically incentivize costly lawsuits that cities and jurisdictions have to defend.

There is another critical issue that comes up, and that is that the police would be allowed to view the recording prior to their report.

As we saw in both the South Carolina shooting and the Cincinnati shooting, officers had given a false story that was later contradicted by video evidence.

Michael Slager shot and killed Walter Scott on April 4 in North Charleston, South Carolina. He immediately began spinning a web of lies to protect himself. First, after shooting eight shots at Walter Scott’s back, the officer walks toward the body. As he walks, he radios in to dispatch, feigning that he is out of breath.

He then creates a false narrative that Mr. Scott had grabbed his Taser. Realizing that he told that to dispatch, he runs 30 feet away to grab his stun gun. Then with the stun gun in his right hand, in the presence of his partner, Clarence Habersham, Mr. Slager drops the stun gun next to the body of Walter Scott. Finally he claims to have performed CPR on Walter Scott – though no such thing has happened.

The video not only contradicts his claims, it shows him concocting these lies. But had he had access to the video before giving his report, perhaps he might have fabricated a more believable story.

In Cincinnati, a police officer was indicted for murder after prosecutors concluded that evidence from the officer’s body camera showed that the victim, Samuel DuBose, did not act aggressively or pose a threat to Officer Ray Tensing, and that Officer Tensing had lied about being dragged by Mr. DuBose’s car.

However, this is not just setting up officers for a gotcha moment. Last night, I heard an interesting story that demonstrates the danger to officers. There was a case in another locale where the officers were transporting a very intoxicated individual to jail.

The individual could not stand and kept falling over as they tried to get him into a doorway. Finally, in frustration, an officer repeatedly kicked the individual into the doorway.

The incident was caught on video from the jail and the investigator made the mistake of allowing the officer and his attorney to view the video prior to making a statement. The officer concocted a transparent series of lies to explain his use of physical force.

The result is that, instead of merely facing an unjustified use of force that was a spontaneous result of frustration, the officer committed a far more damaging offense of intentional dishonesty. By allowing the officer to view the video prior to the report, he actually made matters worse for himself by attempting to concoct a story that fit the visuals of the video.

This issue is by no means limited to Davis – it figures to be a national debate, but if Davis is going to implement a body camera policy, it needs to be done the right way.

The ACLU in its policy statement argues, “Officers involved in a critical incident like a shooting or facing charges of misconduct should not be permitted to view footage of the incident before making a statement or writing an initial report. Police do not show video evidence to other subjects or witnesses before taking their statements. Officers should watch the video after their initial statement and have the chance to offer more information and context.”

They add, “Officers may not remember a stressful incident perfectly, so omissions or inconsistencies in their initial account shouldn’t be grounds for discipline without evidence they intended to mislead. This would provide the fullest picture of what happened without tainting officers’ initial recollection or creating the perception that body cameras are being used to cover up misconduct, not hold officers accountable.”

—David M. Greenwald reporting

*police* body cameras

During a routine home check of a citizen whom a judge referred to as a “model citizen”, I do not appreciate their sleazy cameras on while they rifle through my teenaged daughter’s underwear drawer, my medicine cabinet, my mom’s eulogy and memorial photo’s, my address book, cell phone bill, or my poetry and memoir. I have no idea what members of the police force, possibly voyeurs, could be staring at a video of me in a see through cotton night shirt, or my son in handcuffs. My two cents.

On the other hand, if the probation officer in Antioch had been wearing one, perhaps a caring co-worker, reviewing his video, may have noticed the extension cords hanging overhead, and discovered Jaycee a whole lot sooner.

So where do we draw the line? What kind of mental health assessment is done on cops, probation officers, and the channel 13 news camera man that tried to force his camera into my front door, while the cops stood idly by? How can I can be relatively assured no voyeur is looking at video’s of me, or my teenagers?

The policy they are proposing would preclude cameras in those kinds of situations.

there is a reason that suspects are not allowed (as a general matter) to view the video prior to issuing their statement.

DP

“there is a reason that suspects are not allowed (as a general matter) to view the video prior to issuing their statement.”

Should not that same reason apply equally to the police ?