by Deborah Brusco, Diane Clarke, Elvia Garcia, Kara Hunter, Jeannette Lejardi, and Manuel Medeiros

As our community continues to consider the role of restorative justice in our common life, and especially in light of new opportunities that have emerged around recent local incidents, in this article we’d like to 1) examine how restorative justice constitutes a paradigm shift in the way we respond to crime; 2) highlight a fundamental premise underlying restorative justice: our human interconnectedness; and 3) consider the potential transformative benefits to people and relationships.

Shifting Paradigms: Different Views and Changing Questions About Justice

Restorative justice embodies a paradigm shift in how we respond to crime. Paradigms, in any aspect of life, can be defined as sets of views, or outlooks that govern our attitudes, choices, rules, and behaviors in our individual lives, families, communities, and public institutions. As our views change or evolve, we may embrace amended or even totally new paradigms that alter – sometimes quite significantly – the way we live our lives. Thus, a shift to a new paradigm tends to reflect very significantly altered underlying views and outlooks.

In The Little Book of Restorative Justice, Howard Zehr outlines different views of justice that, taken side-by-side, help to illustrate the profound paradigm shift represented where restorative justice has been embraced (Figure 1).

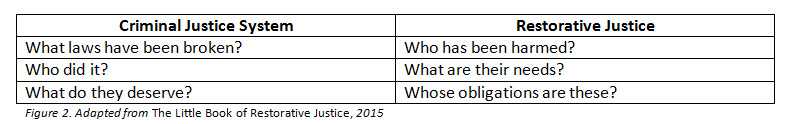

Similarly, Zehr juxtaposes three central questions asked by our criminal justice system and by restorative justice. Restorative justice changes the questions we ask in response to crime (Figure 2):

In contemplating these contrasting views and questions, however, it should be pointed out that our criminal justice system does not inherently exclude restorative justice options. Indeed, restorative justice is now being used in various ways and to varying degrees within the criminal justice system itself. Even viewed merely on a practical level, with our overcrowded courts, jails, and prisons, this trend seems likely to continue.

Surpassing practicality, though, it is evident across our nation, as well as in our own community, that many are sensing personal and shared needs that are different from, or go beyond, those  addressed in our traditional criminal justice system. In other words, far from being just an expediency, or an imposed, top-down theory, restorative justice as an approach to crime has emerged, seemingly ineluctably, and continues to grow from the bottom up, so to speak, in response to our greater awareness of personal and collective unmet needs.

addressed in our traditional criminal justice system. In other words, far from being just an expediency, or an imposed, top-down theory, restorative justice as an approach to crime has emerged, seemingly ineluctably, and continues to grow from the bottom up, so to speak, in response to our greater awareness of personal and collective unmet needs.

A Fundamental Premise of Restorative Justice: “Being Connected in a Good Way”

Underlying restorative justice is the basic recognition that we are all interconnected in our common humanity. And as Kay Pranis posits, in Peacemaking Circles: From Conflict to Community, “every human being wants to be connected to others in a good way.” In fact, Pranis identifies this as a fundamental premise of restorative justice. Thus, restorative justice aims to open the possibility for restored relationships and renewed communities after crime has disrupted – even severely damaged – relationships and communities.

Pranis goes on to observe that being connected in a good way is not easy for us to attain, let alone regain in the face of crime or other harmful incidents. For this reason, restorative justice processes are carefully constructed and facilitated to help create a safe space where, as Pranis says, we can begin to identify shared core values and, eventually, uncover our “deep-seated desire to be positively connected.” Specifically, restorative justice processes are structured around the critical importance of allowing each person’s story to be heard – especially, what they each feel and think about what happened, how this has affected their lives, what they need based on how they have been harmed, and what needs and hopes they have going forward. When people’s stories are shared and acknowledged in this manner, the way is opened for personal and relational shifts and changes that can truly be termed “transformative.”

The Transformative Benefits of Restorative Justice

The above-mentioned outcomes – repaired relationships, things “made right,” restoration of those who have been harmed and those who have caused harm – bespeak the personal and relational metamorphoses that are the potential of restorative processes. These personal and relational shifts are sometimes termed “transformative” because they reflect positive changes (sometimes profound, and often unexpected or surprising) in the feelings participants have toward each other after a restorative process. And although such transformations may be given birth during such processes, by their nature they typically continue to unfold, even over many years, in the lives of individuals and communities who have engaged in such processes. For individuals, this often means new and positive life trajectories. For communities, this can mean ongoing conversations about desired changes in community norms and practices and even shifts in a community’s sense of responsibility for effecting the common good among its members.

The following comments (anonymous) from participants in recent local restorative justice processes help to illustrate how restorative processes can effect positive, transformative changes in people’s lives and relationships.

“I’m super thankful the restorative justice program was available to me. It gave me a chance for a “do-over” and made a big difference in moving my life in a positive direction.” (person who caused harm)

“I was apprehensive at first but then pleased with the way the process worked. I’d definitely recommend it to others.” (person who was harmed)

“The restorative justice process made me realize how what I did was wrong and how it affected people around me.” (person who caused harm)

“Going through the restorative justice process helped my son to understand how what he did affected others and to feel connected to those he harmed.” (parent of person who caused harm)

Please join the Yolo Conflict Resolution Center on Thursday, September 21, 6:00–8:00 p.m., for a Community Forum on Restorative Justice at the Woodland Community and Senior Center, 2001 East Street. Ron and Roxanne Claassen, restorative justice practitioners, trainers, and authors, will speak about restorative justice and its benefits to the community. The event is free and open to the public. To register, visit https://www.eventbrite.com/e/ycrc-restorative-justice-forum-tickets-37281072692.

Deborah Brusco, Diane Clarke, Elvia Garcia, Kara Hunter, Jeannette Lejardi, and Manuel Medeiros are members of the Yolo Conflict Resolution Center Restorative Justice Work Group